Natural layered materials such as bone and mother-of-pearl have many functions. Alongside helping organisms protect and defend themselves, some, such as the shells of marine animals, can also sequester carbon by combining proteins and inorganic composites. Researchers at Pennsylvania State University in the US have now engineered artificial versions of these composites inspired by the ring teeth of squid. The new structures are tough and extremely stretchy, and they might find use in applications such as robotics and flexible electronics as well as in carbon sequestration.

When carbon dioxide dissolves in the sea, it forms carbonate ions that can be taken up by microscopic creatures called coccoliths. These tiny animals build their shells, or exoskeletons, one layer at a time by converting carbonate to minerals like calcite or aragonite. Because biological organisms carry out this process of calcite transformation 1000 times faster than would be possible with purely chemical mechanisms (which normally take 10 000 years), study leader Melik Demirel explains that they could be used to sequester carbon from human-caused CO2 emissions.

Modifying repeating sequences

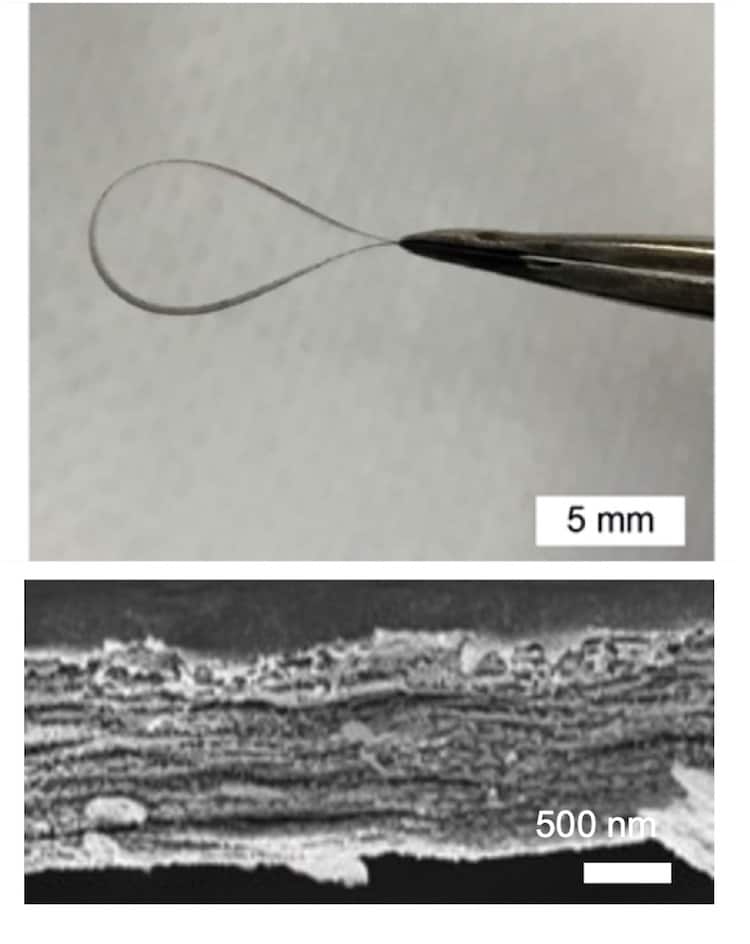

Artificial versions of these composite layered materials typically consist of atom-thick layers of a hard material like graphene or one of the MXenes (usually a transition metal carbide, nitride or carbonitride), separated by layers of a binding material. The strength of these composites stems from the properties of the interface layers and these can be modified by repeating sequences. In this way, a material can be made flexible and strong at the same time.

In their work, Demirel and colleagues studied the mechanical properties of atomically-thin inorganic layers interfaced with so-called tandem-repeat proteins by carefully controlling the latter’s molecular weight. The researchers explain that these proteins, which are known as squitex because they are inspired by the structure of squid teeth, adhere to the inorganic sheets via secondary beta- and alpha-helix structures. This mechanism is crucial as it gives the material a good degree of stretchiness and toughness.

The interface is important

The researchers found that the mechanical properties of their material cannot be explained by an existing model known as continuum theory. Their simulations, however, revealed that the interface is important: when the material contains a higher amount of the interface compound, it breaks in places when the material is under stress, but the material as whole does not break, explains Demirel. “While we expected it to become compliant, it is also super stretchy,” he says. “This finding opens up perspectives on failure mechanisms for composites that depend on interfacial rather than bulk properties.

Bioinspired material can’t be cut

“Controlling interfacial strength ultimately engenders new design rules for nature-inspired composites,” he tells Physics World. “Although bare inorganic nanosheets are brittle, we designed flexible composites with proteins that are robust to flaws at critical structural length scales (of around 2 nm).”

With additional functionality such as electrical and thermal conductivity, the researchers say their tough new materials could find applications in flexible circuit boards, wearable devices or other equipment that requires both strength and flexibility. The Penn State team, which reports its work in PNAS, is now working on scaling up the composites for potential applications in carbon sequestering. “We plan to aim for gigaton sequestration in the next 30 years,” Demirel reveals.