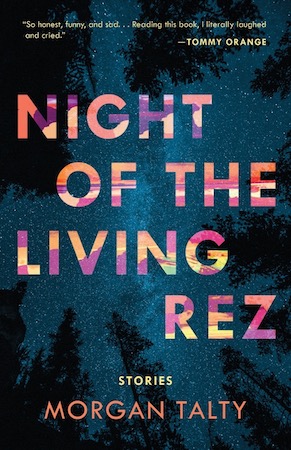

Morgan Talty’s The Night of the Living Rez is a searching and honest collection of short stories following a young Penobscot character named David and his coming of age on the rez, where community, family, and tradition are as fraught with colonial entanglement as they are forces for healing.

With hyperreal and welcoming prose, Talty examines questions like how Natives heal from ongoing colonization, Native invisibility and family dysfunction—but what I loved most about this collection was the way it renders what it feels like to look for your place in the world and not know what it is, or how to find it. To feel like there might be no place, in fact, or at least not one that feels exactly right.

In each story, I felt like I was interrogating the night with Talty’s characters, both running from and towards myself. Both surprisingly and inevitably, The Night of the Living Rez is where I found I could best meditate on the struggles Natives face today; this is because Talty writes his characters from a truly honest place.

Honesty is important to Talty, and in the following conversation, we discuss the power of honest stories to inspire transformation, from problematic medicine men to creating accurate representation of who Indigenous people are today.

Editor’s note: Click here to watch the video component of the conversation between Chelsea T. Hicks and Morgan Talty about their short story collections A Calm and Normal Heart and Night of the Living Rez.

Chelsea Tayrien Hicks: I was delighted to find commonalities in our stories, like the way we both included notes on spelling in our respective languages, and we both also dramatized filmmakers who come in wanting to depict the culture for their own profit. I wanted to ask you about your own intentions in engaging these two areas, both the language and the attraction outsiders have to wanting to tell Native stories. Was there anything you were hoping to address, and what were you hoping to do with these inclusions?

Morgan Talty: I also was delighted to see that! It was assuring in a strange way, like these motifs are, on a broader scale, recurring in real life and have something to say when we use them in our own work.

For me, tribal communities are dealing with internalized colonization, and we’ve moved away from that ‘us’ to ‘me’ mentality.

I was deeply interested in these characters and their emotions, and getting close to them allowed me to tease out ideas about representation and even “being.” Not necessarily what it “means to be Indian,” but what it means to be a human being who just so happens to be Native and thus the colonial history that is part of their chemical make-up. I think it would be irresponsible for me not to explore those types of intentions around language, trauma, legacy, inheritance, and so on. I will admit—there are writers out there who can do it better, but still—I felt a deep responsibility to illuminate these ideas.

CTH: In “Half-Life,” I was fascinated with David’s growing sense of tension between personal responsibility and social pressure. I thought his transforming question about his using [of drugs] was a brilliant way to move him toward a breakthrough. He goes from asking How did we get here? to How did I get here? And how do I get out? His we-to-I reversal reminded me of this saying I’ve seen on Native beading, something like “I to we, me to us.” That saying is meant to promote the concept of decoloniality, but community-mindedness can also have a shadow side. I felt that the judgment and self-righteousness in the community contributed to David’s addiction as much as his own trauma and internal process. Did you think about shadow aspects of community as you wrote at all, and were you hoping to show some of the challenges of tight knit community life?

MT: Absolutely, and I’m super happy to hear you saw this. For me, tribal communities are dealing with internalized colonization, and we’ve moved away from that “us” to “me” mentality. I’m speaking super generally here, but I feel like most tribes valued the collective over individuality—that, to me, is a very Western idea, even when we consider the great thinkers that shaped the West’s mind. I don’t have to tell you this, but the government’s use of colonial tools like blood quantum, for example, are sinister, and have caused so many contemporary problems, especially adding more friction between this “I” and “we” dichotomy. I feel like my drawing attention to this was important. Dee ultimately says something like, “How do we get out of here?” and maybe the question should actually be: “How do we come back together?”

CTH: One topic I desperately want to write about is expressions of Native masculinity—whether problematic, transforming, or healing—but I feel that I’m not the one to do so because I’m not a Native man. All through reading these stories, I was closely thinking about the different ways your characters embody ways of being a Native man. Frick, who I would call a problematic medicine man, has this line in the title story where he’s drinking and he “…had that man-stare looking down on a woman…” and Fellis treats his mom horribly, which makes David angry but he doesn’t really know what to do.

Do you have thoughts on Native masculinity, how it is transforming or not? And what do you think Native men like David did or are doing to stop cycles of abuse?

We think about the tribes whose councils were all women, but when white men couldn’t get what they wanted, they introduced ideas of paternalism and patriarchy that completely reversed the roles.

MT: To talk about this, I have to bring up the fact that it was mostly women who raised me: my mom, my sister, my aunts. Men were there, sure, but I never really gravitated toward them. As a boy, I had a deep suspicion about men. How could I not? Having been so close to women growing up, I was able to see—and feel somewhat—the pain they experienced at the hands of men, physically and emotionally. To me, Native masculinity is a product of western masculinity—that internalized colonization. We think about the tribes whose councils were all women, but when white men couldn’t get what they wanted, they introduced ideas of paternalism and patriarchy that completely reversed the roles. Today, I feel like we’re still somewhat in that place: where Native men have taken on that patriarchal view. But then, as you ask, what do we do to stop this cycle of abuse? I feel like it has a lot to do with reclaiming not some specific gender roles, but reinventing what it means to live outside the boundary that colonialism has created, that boundary over which runs rampant the violence enacted against Native women. Men—including myself—need to be better, need to do better.

CTH: You dramatize racism in a rez border town, from the bank that doesn’t recognize David’s tribal ID to the newspaper that maligns the rez teenagers by making the white man who harasses them into a seeming victim in a crime. For me, this brought up the fact that Native issues are either not reported on by the popular media, or these same issues are misrepresented. Would you say a bit on how you think about representation in literature, and if it can make a difference in real life issues?

MT: I definitely think it can make a difference. I think it’s our hope that government officials or people in positions of power read, and if that hope is true, then we are exposing them to stories they may not necessarily know about, stories concerning Native issues. I feel like every President and governmental personnel should be required to read diverse literature. I’m serious! I feel like even in law programs, there has been much more emphasis placed on reading literature, which undoubtedly shapes those readers.

CTH: We both wrote stories that engage guilt, but I was struck with the searing way you showed jealousy and denial. Fellis hates Meekew for going to college and acting white, while David’s mom can’t accept reality and both enables Frick’s abuse and neglects David, also contributing to Bedogi’s death. You depicted denial so clearly in the way she misremembers her own actions and misplaces her guilt onto David. What, in your opinion, makes for the most honest story? And do you think David achieves the honest telling he set out to?

MT: My hope is that David does achieve that honesty! It’s certainly something I wanted to do. To me, the writing that is best able to capture that feeling of honesty is the type of writing that dares to reveal its characters’ horrible traits, and not for any shock factors. I mean, sure, from a craft point of view this seems obvious, right? Making sure our characters are flawed. But I feel like it goes beyond this simple craft element and has a lot more to do with the writer really trying to get at the heart of that flaw—again, going beyond an attempt to create a shock factor. Honest writing, to me, is writing that dares to explore the dangerous for the sake of bettering ourselves.

CTH: There’s this beautiful line from “In a Field of Stray Caterpillars” describing Fellis’s eyes as:

“… droopy and soft yet sharply focused, as if the electrical currents searing across his brain had awoken something, something that had rested for far too long and was now awake with a dedication to look through Fellis’s eyes and relay to the brain everything as pure sparkle and gold, even if what it saw was only a cold waiting room with bland white walls and old magazines…”

You write a spectacular long sentence, and I have to tell you I am a passionate fan of this form. Do you have a particular love for the long sentence? I’d love to hear some of your thoughts, in terms of what they can do, and of course any sentence-crafting literary influences.

MT: Long sentences are just fantastic. They’re so hard to write, but they’re so rewarding. Like, when I draft a long sentence, it’s so much fun going back through it and making sure all the details are ordered in just the right way, and making sure the sentence should even be a long sentence. I feel like long sentences somehow break rules—when reading a long sentence, I almost always feel like time no longer exists, like all that there is is right there on the page, and nothing more. I mean, this is true for shorter sentences too, but the long sentence, when it’s right, has the authority to command your attention and is basically saying, “This is important.”