In a tribute to her teacher being named the 2020 laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature, a past protégée offers a glimpse into Glück’s renowned generosity in the classroom and beyond.

At the beginning of September 2009, I arrived fifteen to twenty minutes early to my first poetry workshop class at Boston University. My professor was Louise Glück. I had loved her work since discovering it in the late 1990s, and she’d been the reason I applied to BU’s MFA program. That morning, Louise was the first person to enter the famous room 222 where Robert Lowell had once taught Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and George Starbuck. When she introduced herself, she tucked her hair behind her ear, which caused her gold hoop earring to drop and roll toward my feet. I made to go pick it up, but she was faster. I remember wondering if there was a metaphor in all this: did her earring choose me? Of course, the world was revolving around me then and though I know that it meant nothing, I’ll let my younger self still hold on to that fantasy.

In the year that followed, we met with Louise once a week either in class or at her house in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Sometimes she’d invite all of us in, sometimes we got to meet her individually to talk about our poems. White walls and white furniture blended in with the light from the windows. Her home was luminous and had a vacantness that felt welcoming: from this white space, like the white page, you could breathe and write about anything.

In poems, and at work as a teacher, Louise was a master at swerving, surprising you with the unexpected way she looked at things.

From the beginning with Louise, I could never predict what she would see in our poems. She would usually let us respond to the work first, and afterward it was as if she’d been waiting to contradict us. I didn’t know then that she was doing what Louise does best—in poems, and at work as a teacher, she was a master at swerving, surprising you with the unexpected way she looked at things. But it was not the kind of surprise that comes from acrobatic, linguistic tricks. She’s a master at swerving because arriving at truth is never linear. For decades, she’s been in the business of shattering our preconceived notions about themes like love, death, loss, joy, loneliness in order to present a clearer reality.

In 2013, two years after I finished my MFA, my first book of poems, Bread on Running Waters, came out. I hadn’t seen Louise in person in at least a year, but I mailed her a copy, thrilled to think she would have my book in her home. Sometime later, I received a letter in the mail stuffed in an envelope from Yale University’s Department of English. She used to send letters in envelopes with Yale’s or Stanford University’s address crossed out and her own home address written just under it. I held the letter up to the light, “Lux et Veritas” watermarked in the center. This is what I loved about her—I don’t know to whom else she wrote on paper like this, but I assume she did for all of her students, and this small gesture made it all the more real that in being her students we mattered equally.

This letter meant the world to me then and always will. My debut book came out through Fenway Press, a small, independent publisher out of Newton, Massachusetts, and getting this handwritten letter from Louise felt like a timeless review.

Back in workshops, I saw her working like a surgeon when critiquing, scanning the poem as through an X-ray, seeing its bones and pointing right out where inflammation resided. I often thought of her as a surgeon with a scalpel long before she told us that her father and his brother-in-law were responsible for the X-Acto knife arriving in the world.

She made me aware when I was getting lazy, or when a poem was weaker than my other work. So when I got her letter, I learned that she’d seen me all along. Having taught writing for the past almost twenty years myself, I’ve noticed how often I get so excited by my students’ work that I worry sometimes if by not restraining my joy, I’m hurting their revision process. Louise showed restraint, so the rare times you heard her praise your work, it really counted.

Louise showed restraint, so the rare times you heard her praise your work, it really counted.

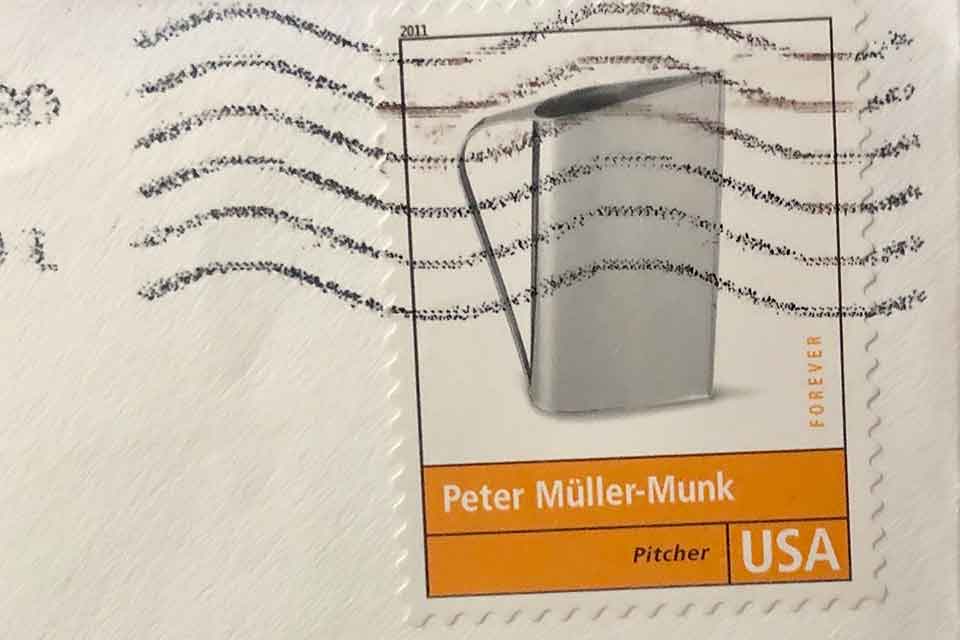

The postage stamp she had stuck to the envelope had the image of a Peter Müller-Munk pitcher on it that I had not noticed until now. Made from a single sheet of brass to imitate the form of a ship’s prow, the pitcher was inspired by the SS Normandie ocean liner after which he’d named it. Sleek, elegant, it stands at attention. Looking at it, you might imagine it pouring cool, crystal water.

It reminds me of how in conversations and workshops, Louise taught us to trust where curiosity and attention lead us. And through books like Ararat, The Wild Iris, Meadowlands, she taught me that a poem must move two steps ahead of the reader, until just before the ending, where both the writer’s and the reader’s realizations align.

Framingham, Massachusetts