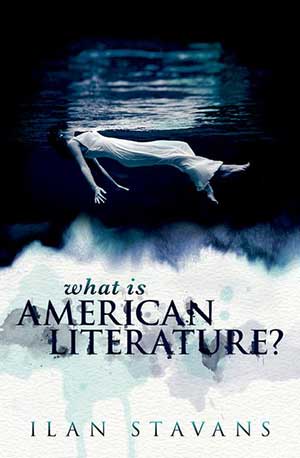

In his newest book, What Is American Literature? (Oxford University Press, 2022), award-winning cultural commentator, translator, and editor Ilan Stavans, the publisher of Restless Books and the Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities and Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College, rereads an assortment of American literary classics through the prism of the Trump years, from the poems of Phillis Wheatley to Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. In the primer, written during the presidential election won by Joe Biden—and before the January 6, 2021, sedition instigated by Donald Trump—he also reflects on the role public libraries play in disseminating the nation’s literature, the art of teaching it to new generations of students, and the future of the book as an artifact disseminating knowledge in our graphic-driven age. The volume closes with an epistolary account, in Stavans’s words, of “the Second American Civil War.” What follows is the section on teaching.

American literature starts and ends in the classroom. It starts there because whoever is a writer-to-be is likely to discover the magic of literature as an assignment, or else in response to the tedium that comes from feeling disengaged with the educational purpose.

American literature starts and ends in the classroom. It starts there because whoever is a writer-to-be is likely to discover the magic of literature as an assignment, or else in response to the tedium that comes from feeling disengaged with the educational purpose.

And it ends in the classroom because, at a time of precipitous declines in reading habits, books have their largest audiences among students enrolled in this or that course.

Reading for pleasure is one thing, and another altogether different thing is being obligated to read. The latter has a pernicious effect. It might traumatize readers who on their own are unlikely to find pleasure in the artfulness of a book. There is nothing worse than a teacher forcing a student to read. Unless you write a report, you will blah-blah-blah.

I myself was an apathetic reader when I was young. I didn’t quite feel repulsion for books, but the emotions I experienced weren’t far from it. The duty to read for a class made me dislike any interesting book that came my way.

Until things changed. Why and how I can’t quite explain. As I remember, it happened around seventeen or eighteen. From one day to the next I was an avid reader. I have never looked back.

When I was young, I also never thought of myself as a teacher. Why would anyone want to spend most of their life indoors with a bunch of rowdy kids? Yet I can’t think of anything more rewarding than teaching. Or more challenging.

I’m a professor at a small liberal arts college in New England, but I don’t like the word “professor.” It is too snobbish. I also don’t like the word “academic.” It makes me feel isolated, detached.

I prefer to be called a teacher. I didn’t set out to become one. In some ways, I became a teacher out of necessity. I’m an immigrant from Mexico. I needed a visa. Teaching seemed like a worthy route to getting one.

I teach literature not only to college students. I also teach Shakespeare in prisons. I teach in public libraries to a population that is truly diverse. I teach in senior facilities. And in the summer, I teach middle- and high-schoolers. I love books. My mission is to make students love them as well. I open them in front of their eyes. Not just any book, but what I call “tested books” by writers of all backgrounds—Whitman, Dickinson, Melville, Hawthorne, Saul Bellow, Baldwin, Paley, Nabokov, Bashevis Singer, Toni Morrison, Henry and Philip Roth—that have survived the passing of time. In other words, the classics.

I particularly enjoy teaching the classics. I love the fact that as an immigrant, I get to introduce Americans (most of my students have been born in the United States) to the literary tradition that defines them. I approach these books as an outsider who has entered the banquet. I do so by choice.

I love the fact that as an immigrant, I get to introduce Americans (most of my students have been born in the United States) to the literary tradition that defines them.

Teaching American literature is a contested endeavor. Obviously, it is all about representation: who gets to tell the story of the nation and in what way that story is told. Since the past is never settled, neither is literature. This means that the reaction a new crop of students is going to have to a book I have taught numerous times is likely to surprise me. It might even unsettle me.

No wonder the classics are under siege. They are seen as biased, dubious, and suspect. I tell students that classics are books we don’t only read but reread. That is, they have to survive scrutiny, which is no easy feat.

As I see it, there is nothing wrong with rejecting the classics. The transmission of knowledge shouldn’t be mechanical. Each of us needs to discover a classic afresh because the classics were not written for abstract readers. They were written specifically for us. If we don’t like them, we should read other classics.

Each of us needs to discover a classic afresh because the classics were not written for abstract readers. They were written specifically for us.

Ours is an age of intolerance that really doesn’t value books. Washington is the land of distrust. The nation has recently been commanded by a Latin American–styled tyrant who not only doesn’t read (the book he wrote was concocted by someone else) but whose lexicon seems to consist of 750 words. To a large portion of the country, difference is a threat.

In our own community, the disease of intolerance is present. Before the presidential election, racist and anti-Semitic graffiti appeared on Mount Tom. Likewise, anti-immigrant, xenophobic, sexist, and misogynistic incidents have been reported in our public schools.

Prejudice doesn’t live outside campuses only. Liberals, who fashion themselves as free of bigotry, can be just as chauvinistic. Opposing views that are considered unwelcome are shut down. Students of the current generation—the cool, distracted millennials—are imbued with preconceived ideas that are equally narrow-minded.

The whole brew is toxic. Truth is frowned upon. Nothing matters because nothing lasts. All of which makes teaching more important than ever.

The classroom cannot be divorced from the real world, even when that world is in a state of disarray, as is ours. Each classroom must be a testing ground where ideas are pondered thoroughly. It must also be the place where we slow down. In the classroom, we must take stock. Yes, there ought to be debates, but it is useless if those debates are screaming matches or based on dismissive attitudes. The classroom must lead by example.

In the current climate, Updike and Bellow are out. (Dead white men talking meanly about women!) Dickinson is an eternal source of love. (She’s mysterious. Plus, in the eyes of students her poems are mercifully short.) Adrienne Rich’s feminist voice is strident. Junot Díaz, the most aesthetically ambitious Latino writer of his generation, was accused of disrespecting women. Likewise, Langston Hughes’s closeted homosexuality is perceived to be a problem, unless it might be argued that it was a strategy of self-defense.

Along these lines, not long ago I had a Latino student who looked down at anything a white person said because, she said angrily, it was “biased with privilege.” Her position was understandable. She came from a neighborhood in Los Angeles where interaction with non-Latinos was minimal. Montaigne once said that “we call barbarous anything that is contrary to our own habits.” It was only after the class engaged with other kinds of difference that the student felt more at home.

To me, the classroom is where we fine-tune our better selves. It is where we discover what we don’t know and where we question everything. Doubt rules in the classroom because doubt is the door to knowledge. And knowledge must be won. Nothing should be taken for granted.

Doubt rules in the classroom because doubt is the door to knowledge.

Especially any text that binds us, including the U.S. Constitution. If there is anything that will serve as social glue, it has to be thoroughly interrogated.

Words uttered in the classroom must be made to matter; they must be listened to fully and patiently, not only for what they mean but for how they sound: their music, their rhythm. Likewise, the classroom is where silence must be given its due. I love the sound a student makes before words come out and when thought is still being processed. There is a hiatus, a pause. That pause is the seed of wisdom.

And what about the teacher? In my view, the teacher is a companion, like Virgil in the Divine Comedy. An authority, yes, but not authoritarian. And certainly not a know-it-all.

Teaching is what anchors me. It has been more than twenty-five years since I started doing it. I wouldn’t give up a single minute of it. But it goes without saying that teaching today is a battered and embittered career. Teachers are blamed for all sorts of ailments: reading failure, low test scores, poor academic performance. The result is that teaching isn’t often an attractive option for our undergraduates.

Yet teaching—I say this with absolute certainty—is an essential endeavor, again particularly when it comes to the endeavor of bringing literature to the attention of the next generation. It is about honoring who we are. The classroom is where intellectual curiosity is at home, where our cultural values are shaped. It is where people think, individually as well as in groups. For that reason, it is crucial that we again make teaching the revered, humble vocation it used to be.

As our nation goes through this rough, ugly period, hopefully one that will pass soon, the classroom is where humanity starts.

Amherst College