The whirlwind weekend in late April that saw the country’s biggest bank take over its most troubled regional lender marked the end of one wave of problems — and the start of another.

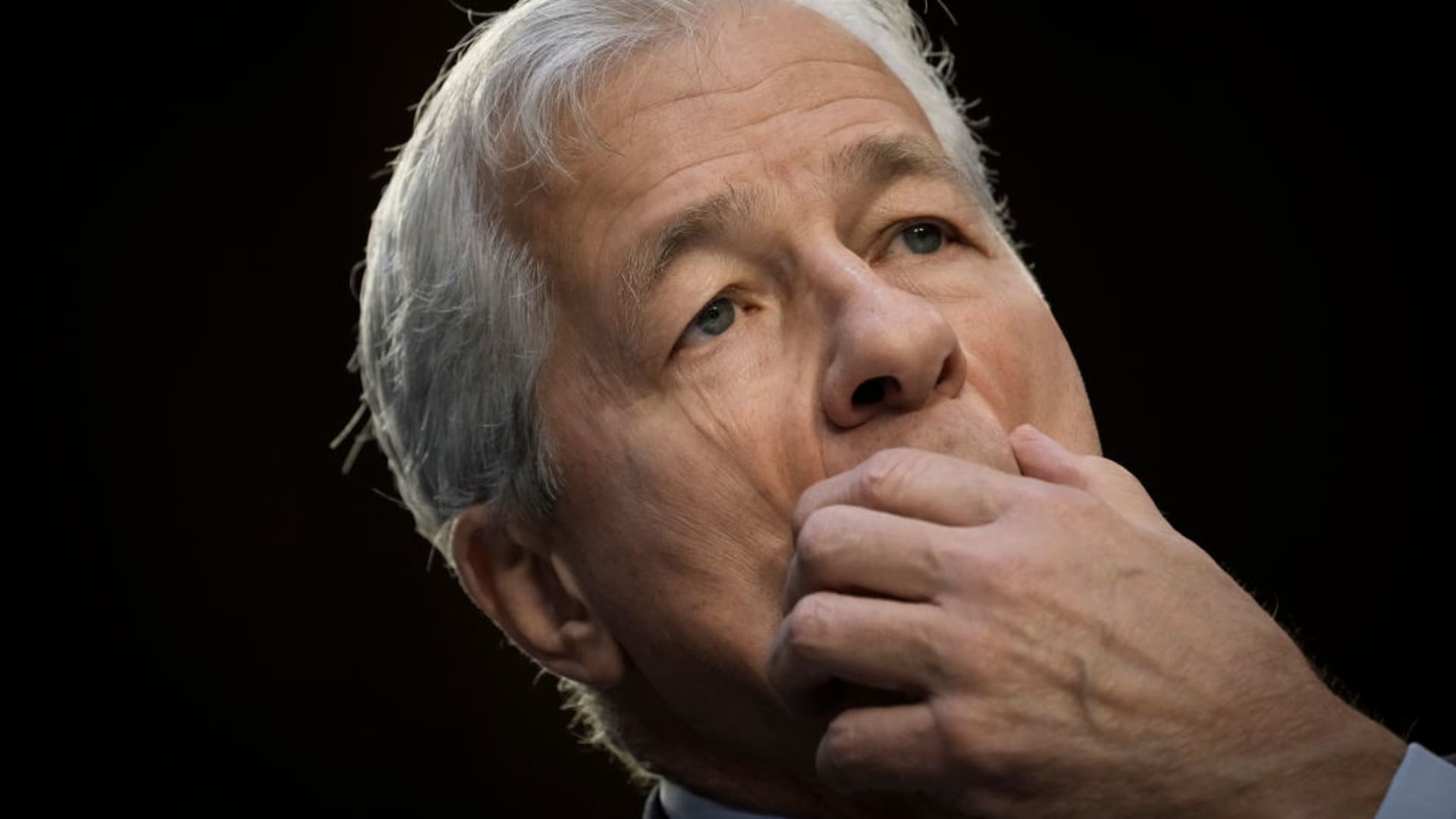

After emerging with the winning bid for First Republic, the $229 billion lender to rich coastal families, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon delivered the soothing words craved by investors after weeks of stomach-churning volatility: “This part of the crisis is over.”

But even as the dust settles from a string of government seizures of failed midsized banks, the forces that sparked the regional banking crisis in March are still at play.

Rising interest rates will deepen losses on securities held by banks and motivate savers to pull cash from accounts, squeezing the main way these companies make money. Losses on commercial real estate and other loans have just begun to register for banks, further shrinking their bottom lines. Regulators will turn their sights on midsized institutions after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank exposed supervisory lapses.

What is coming will likely be the most significant shift in the American banking landscape since the 2008 financial crisis. Many of the country’s 4,672 lenders will be forced into the arms of stronger banks over the next few years, either by market forces or regulators, according to a dozen executives, advisors and investment bankers who spoke with CNBC.

“You’re going to have a massive wave of M&A among smaller banks because they need to get bigger,” said the co-president of a top-six U.S. bank who declined to be identified speaking candidly about industry consolidation. “We’re the only country in the world that has this many banks.”

How’d we get here?

To understand the roots of the regional bank crisis, it helps to look back to the turmoil of 2008, caused by irresponsible lending that fueled a housing bubble whose collapse nearly toppled the global economy.

The aftermath of that earlier crisis brought scrutiny on the world’s biggest banks, which needed bailouts to avert disaster. As a result, it was ultimately institutions with $250 billion or more in assets that saw the most changes, including annual stress tests and stiffer rules governing how much loss-absorbing capital they had to keep on their balance sheets.

Non-giant banks, meanwhile, were viewed as safer and skirted by with less federal oversight. In the years after 2008, regional and small banks often traded for a premium to their bigger peers, and banks that showed steady growth by catering to wealthy homeowners or startup investors, like First Republic and SVB, were rewarded with rising stock prices. But while they were less complex than the giant banks, they were not necessarily less risky.

The sudden collapse of SVB in March showed how quickly a bank could unravel, dispelling one of the core assumptions of the industry: the so-called “stickiness” of deposits. Low interest rates and bond-purchasing programs that defined the post-2008 years flooded banks with a cheap source of funding and lulled depositors into leaving cash parked at accounts that paid negligible rates.

“For at least 15 years, banks have been awash in deposits and with low rates, it cost them nothing,” said Brian Graham, a banking veteran and co-founder of advisory firm Klaros Group. “That’s clearly changed.”

‘Under stress’

After 10 straight rate hikes and with banks making headline news again this year, depositors have moved funds in search of higher yields or greater perceived safety. Now it’s the too-big to-fail-banks, with their implicit government backstop, that are seen as the safest places to park money. Big bank stocks have outperformed regionals. JPMorgan shares are up 7.6% this year, while the KBW Regional Banking Index is down more than 20%.

That illustrates one of the lessons of March’s tumult. Online tools have made moving money easier, and social media platforms have led to coordinated fears over lenders. Deposits that in the past were considered “sticky,” or unlikely to move, have suddenly become slippery. The industry’s funding is more expensive as a result, especially for smaller banks with a higher percentage of uninsured deposits. But even the megabanks have been forced to pay higher rates to retain deposits.

Some of those pressures will be visible as regional banks disclose second-quarter results this month. Banks including Zions and KeyCorp told investors last month that interest revenue was coming in lower than expected, and Deutsche Bank analyst Matt O’Connor warned that regional banks may begin slashing dividend payouts.

JPMorgan kicks off bank earnings Friday.

“The fundamental issue with the regional banking system is the underlying business model is under stress,” said incoming Lazard CEO Peter Orszag. “Some of these banks will survive by being the buyer rather than the target. We could see over time fewer, larger regionals.”

Walking wounded

Compounding the industry’s dilemma is the expectation that regulators will tighten oversight of banks, particularly those in the $100 billion to $250 billion asset range, which is where First Republic and SVB slotted.

“There’s going to be a lot more costs coming down the pipe that’s going to depress returns and pressure earnings,” said Chris Wolfe, a Fitch banking analyst who previously worked at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

“Higher fixed costs require greater scale, whether you’re in steel manufacturing or banking,” he said. “The incentives for banks to get bigger have just gone up materially.”

Half of the country’s banks will likely be swallowed by competitors in the next decade, said Wolfe.

While SVB and First Republic saw the greatest exodus of deposits in March, other banks were wounded in that chaotic period, according to a top investment banker who advises financial institutions. Most banks saw a drop in first-quarter deposits below about 10%, but those that lost more than that may be troubled, the banker said.

“If you happen to be one of the banks that lost 10% to 20% of deposits, you’ve got problems,” said the banker, who declined to be identified speaking about potential clients. “You’ve got to either go raise capital and bleed your balance sheet or you’ve got to sell yourself” to alleviate the pressure.

A third option is to simply wait until the bonds that are underwater eventually mature and roll off banks’ balance sheets – or until falling interest rates ease the losses.

But that could take years to play out, and it exposes banks to the risk that something else goes wrong, such as rising defaults on office loans. That could put some banks into a precarious position of not having enough capital.

‘False calm’

In the meantime, banks are already seeking to unload assets and businesses to boost capital, according to another veteran financials banker and former Goldman Sachs partner. They are weighing sales of payments, asset management and fintech operations, this banker said.

“A fair number of them are looking at their balance sheet and trying to figure out, `What do I have that I can sell and get an attractive price for’?” the banker said.

Banks are in a bind, however, because the market isn’t open for fresh sales of lenders’ stock, despite their depressed valuations, according to Lazard’s Orszag. Institutional investors are staying away because further rate increases could cause another leg down for the sector, he said.

Orszag referred to the last few weeks as a “false calm” that could be shattered when banks post second-quarter results. The industry still faces the risk that the negative feedback loop of falling stock prices and deposit runs could return, he said.

“All you need is one or two banks to say, ‘Deposits are down another 20%’ and all of a sudden, you will be back to similar scenarios,” Orszag said. “Pounding on equity prices, which then feeds into deposit flight, which then feeds back on the equity prices.”

Deals on the horizon

It will take perhaps a year or longer for mergers to ramp up, multiple bankers said. That’s because acquirers would absorb hits to their own capital when taking over competitors with underwater bonds. Executives are also looking for the “all clear” signal from regulators on consolidation after several deals have been scuttled in recent years.

While Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has signaled an openness to bank mergers, recent remarks from the Justice Department indicate greater deal scrutiny on antitrust concerns, and influential lawmakers including Sen. Elizabeth Warren oppose more banking consolidation.

When the logjam does break, deals will likely cluster in several brackets as banks seek to optimize their size in the new regime.

Banks that once benefited from being below $250 billion in assets may find those advantages gone, leading to more deals among midsized lenders. Other deals will create bulked-up entities below the $100 billion and $10 billion asset levels, which are likely regulatory thresholds, according to Klaros co-founder Graham.

Bigger banks have more resources to adhere to coming regulations and consumers’ technology demands, advantages that have helped financial giants including JPMorgan steadily grow earnings despite higher capital requirements. Still, the process isn’t likely to be a comfortable one for sellers.

But distress for one bank means opportunity for another. Amalgamated Bank, a New York-based institution with $7.8 billion in assets that caters to unions and nonprofits, will consider acquisitions after its stock price recovers, according to CFO Jason Darby.

“Once our currency returns to a place where we feel it’s more appropriate, we’ll take a look at our ability to roll up,” Darby said. “I do think you’ll see more and more banks raising their hands and saying, `We’re looking for strategic partners’ as the future unfolds.”