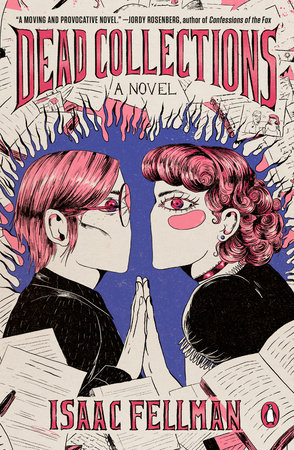

Isaac Fellman’s novel Dead Collections is a sticky book. Content-wise, I mean: Its characters’ immediate concerns are largely driven by various liquids being too slow, too viscous, or in the wrong place altogether.

Sol, the vampire archivist trans man protagonist—yes, all those things, keep up—needs regular blood transfusions to stay “alive,” or un-alive-but-sentient, however you prefer. In the hours before his weekly transfusion, Sol’s blood circulates sluggishly, sapping him of energy. Early in the novel, he takes a very bleak, very hot shower to try and get his blood pumping more freely and to wash away some of the uncannily stagnant sweat that accumulates atop his semi-responsive flesh. It’s the most visceral, least hygienically-satisfying shower scene I’ve ever read. I think about it, like, twice a week.

That’s the other sticky thing about the story: there’s a scene where a guy takes a shower—that’s it! He just showers!—and I’ve been thinking about it for months. It’s not because Dead Collections is wanting for events; the novel combines action, mystery, romance, the paranormal, melodrama and a half-dozen other genres into a remarkably fulfilling blitz of a book.

Sol’s professional life is spiraling out of control, partially caused by stickiness of his own doing (after-hours sex with a new partner in his office) and partially due to external stickiness (archival materials decomposing rapidly and for unclear reasons, the walls themselves becoming damp and musty, abrupt slime problems). The humors of Sol’s (after)life are imbalanced, and he spends Dead Collections trying to, if not correct them entirely, at least get his juices flowing again.

With so much going on, Fellman doesn’t waste a moment between the action. If a character takes a shower, goddammit, you’re going to remember that shower. That might be the key to why this book stuck with me long after I read it—Felmman sweats the small stuff. Even when the small stuff is literally sweat.

Calvin Kasulke: Can you talk to me about your decision to write about vampirism as a medical issue, rather than one that’s strictly supernatural?

Isaac Fellman: I am interested in the supernatural only insofar as it allows me to shortcut and shunt characters into unexpected mental states, in unexpected orders. I also find it metaphorically interesting—sometimes—but mostly I just think of the supernatural as a tool, like a scalpel, by which I can expose more of my characters.

As a writer, you spend so much time moving your characters from interesting mental state to interesting mental state, and the strictly natural world gives us fewer opportunities to do that. Which is why, even though I don’t really think of myself as a genre guy, most of my work has supernatural elements.

Also, I’m interested in medicine and in characters’ experiences of disability. Disability is an experience, as members of the community often observe, that people go in and out of. You have no guarantee that you are never going to be disabled, or if you’re disabled, you often have no guarantee that it’ll last forever. It’s a common and a normal experience, and so it felt natural to look at being a vampire through the lens of chronic illness: something that’s rough, sometimes provides insight, often involves a struggle to get accommodation and care.

CK: Right, even a paranormal experience like vampirism is going to include the kind of quotidian challenges that a medical disability presents.

IF: I really wanted to focus on the day-to-day grind of: By what mechanism does [Sol] get blood in this very medicalized world of vampirism? What is the blood clinic like? What are the chairs there like? Who is motivated to work there? Is it in a nice place, is it a pleasant environment, or is it not? It’s definitely not.

I’m not making this book sound very cheerful. It’s actually an extremely fun book, to my mind, but sometimes you’ve got to get a colonoscopy in this fallen world. Sometimes you have to go to a terrible medical place, where you sit on a recliner that has the imprint of a million butts on it, and get all your blood re-circled. That’s just how it goes.

CK: So, Sol is a trans man and an archivist. You are a trans man and an archivist. Are you, like Sol, a vampire?

IF: I put it in my bio that I’m not, and that’s my final word on the matter.

CK: That’s fair. My actual question is: With those similarities between you and Sol—vampirism notwithstanding—are you at all concerned about the book being read as autofiction?

IF: I do worry about it being read that way. I have another book coming out this year that is, in a lot of strange ways, a lot more autobiographical. Even though Sol shares a ton of biographical details with me, in a way that the main character of this other book does not—

CK: Being a telekinetic, academic, PhD candidate, woman.

IF: Right. Not to mention a straight woman, and one who has been in an abusive relationship with a man, which is an experience that I actually haven’t had. Nonetheless, the stuff that’s going through this woman’s brain is so much more like my brain than the stuff that goes through Sol’s brain.

It felt natural to look at being a vampire through the lens of chronic illness: something that’s rough, sometimes provides insight, often involves a struggle to get accommodation and care.

It’s almost like writing about somebody who is not much like me is what freed me to write about experiences that I have. If a character is too unlike you, it becomes an intellectual slog. If they’re too much like you, then it becomes a different kind of intellectual slog because you’re not analyzing, you’re not interpreting, and you’re not being surprised by the character. It’s why my characters have biographical stuff in common with me, or emotional and intellectual vibes in common with me, but never both.

Autofiction is not a thing that I think is bad, I just want people to assume the right books are auto fiction. In this particular case, it’s not. Although, obviously, I literally put his job on the same street corner as mine. It is not subtle. People will recognize physical places that I know. It is embarrassing, because the book is also about San Francisco and my love of the Bay Area. So I wanted to capture all of those weird little tricks of the light and weird street corner markets where shoplifted items are sold.

CK: This is your only book that’s set in a place that exists, right?

IF: It’s my first book that’s in a place that exists, discounting the books that I never published that died in terrible ways.

CK: Do you want to talk about your unpublished books that died a horrible death to become part of this book?

IF: Much of Dead Collections is centered upon an archival collection by a person who was a TV writer in the ’90s and created some iconic work, especially to queer people. It occupied a similar cultural place to Xena: Warrior Princess or Buffy, in the sense that if you knew, you knew.

CK: And that writer has since passed, and in her archives is this big unfinished novel that’s supposed to be a sequel to the TV show she wrote.

IF: Right. Sol thinks, oh my God, this thing that I was an obsessive fan of, that really defined my youth, I’m going to read the sequel novel that she wrote.

[I’m] examining the ways that some transmascs have used fandom as both a way to imagine transition, but also to avoid transitioning or thinking about it.

And the punchline of this, which is a very common archival experience—in that you think something is going to change your life in the course of your research and it doesn’t—is that it is not a good book. And it is such a bummer. It’s just so clearly the work of somebody who is creatively stuck, and it’s not really redeemable.

All of those excerpts are lightly edited excerpts of a book that I wrote about five years ago that didn’t go anywhere. In the end, I thought that it was too much of a mess to want to tidy up. The only thing that I really liked about it were the ideas for the world, and that all made it into this one, but I deliberately took things out of context so that it looks worse.

CK: That iconic show, Feet of Clay, is the one that Sol was really into as an early teen. What fandoms were you into around that age?

IF: A lot of what is going on in Dead Collections is me examining the ways that some transmascs, specifically, have used fandom—empathizing deeply with male characters and writing about their relationships and all of this stuff—as both a way to imagine transition, but also to avoid transitioning or thinking about it, because you have this safe place where your big feelings about masculinity can go. It’s a thing that for Sol, in the book, is often very painful to remember.

In fact, there’s a flashback to when the two main characters of the book met in fandom at the time. And their interaction was cruel and intellectually sophomoric. Both of them were clearly in a lot of pain, for gendered reasons that they could not acknowledge. And so, as a result of associating fandom with this particular aspect of my transmasculinity, I didn’t have any interaction with it for many years. But recently I actually have reconnected with it, and I have been writing and reading it again.

The historical fiction [novel] that I am writing now is based upon original research that I ended up doing as a result of being interested in historical fiction on the same topic. So now I’m doing an original story based on the same universe where I have written fanfic—which actually has been incredibly creatively productive because to me, the best way to be creatively productive is to self-own as much as possible. Just commit to doing the most circuitous and commercially untenable creative task possible, and eventually you will come up with something that loops around to being commercially viable.

The path to originality always lies through pursuing one’s obsessions. If they are obsessions with a third party piece of material, the route to originality is through those pieces of material. This is true of people who are writing fanfic and then adapting it into original work; It is also true of people who are simply writing fanfic. That’s the thing that I think people don’t understand about fanfic. It is often wildly original, and ends up being that way through releasing the obligation for work to be about you in any way, because it’s patently about some guy on TV. You end up unlocking some really fascinating levels of weird that it’s harder to access sometimes, when you don’t have that freedom of “It’s not me, it’s not about me.”

CK: There’s been a lot of vampire media in the last decade or two. Was there any vampire content you wanted to consciously avoid, or anything you simply couldn’t avoid?

IF: It is just astonishing how completely I have avoided vampires, culturally. It’s hard to name a trope that I’m actually less interested in inherently. I believe I saw the first Twilight movie once. I am definitely aware of everything that happens in The Vampire Chronicles, because I have the kinds of friends who, when we were younger, would simply describe books to me, as I’d describe books to them. We were young people of certain persuasions.

God knows, we’ve all read the work of somebody who’s never written fantasy before. They’ve always written hard literary fiction, and they’re like, I’m going to write a lovely little fantasy book and I’m going to use the first five ideas that I have. I’m sure they’re very original. And of course, they’re the five greatest clichés of the field, and they simply don’t know. I don’t want to insult people who like vampires, the ways that you insult people who like fantasy by thinking, “And it’s going to have a dragon, but this dragon can talk.” Any similarity to real examples is coincidental.

You can’t really write a romance without exposing the kind of romance that you want. That’s hard enough to do even to a potential romantic prospect.

But because you have the cultural osmosis of vampires, you can’t not think of them. I am aware of the ways that Buffy subverted and did not subvert the sexy vampires of Anne Rice. You know what’s going on in the world of vampires, whether or not you plan to or want to. And I think that my disinterest in them has a lot to do with the fact that I couldn’t avoid them. I don’t make any claims to originality in this, but the route by which I became fascinated by vampires and realized that they are in fact interesting, and they are very sexy and cool, is making the vampirism suck. No pun intended.

Once I realized that I could make it terrible, I was like, oh yeah, I love writing about people who are having a terrible time. He is going to have to go to this clinic. And then people will be weird to him. Because I love writing about people being weird to you. It’s a really underrated emotion to explore in fiction. It’s not fun to experience, but it sure is fascinating to write about.

CK: So there are two pretty major romances in Dead Collections, one that happens in the past tense and one in the present. What kinds of romantic relationships are you attracted to writing?

IF: I love writing romance. I don’t always do it, but it’s not because there’s a lack of pleasure in it. It’s because romance is intensely personal. You can’t really write a romance without exposing the kind of romance that you want. That’s hard enough to do even to a potential romantic prospect, much less to the entirety of the English-speaking public.

This book really called out for a really intense, really emotional romance that, to be clear, is very heightened. It speaks to a desire in me, but not a literal one.

CK: We keep returning to this idea of writing about subjects that aren’t too personal, but also aren’t too distant from your experiences or desires. How was writing a heightened romance, as you said, like the one in your book?

IF: Usually I am interested in writing about relationships between people who have really been through it and who struggle with intimacy as a result, and who have still found a way to an intimacy that is quiet and everyday and moving, because they make it work every single day. These relationships are about building something —a lifelong bond of mutual support. For Sol and Elsie, the relationship is about tearing something down—depression, the closet.

And it’s got flaws. I will go on record as saying that I do not think that it will last the whole lives of these characters. It may not even last a few years. It’s volatile. It’s something that they begin quickly and that is marked by over-the-top passion, which is expressed on both parts, somewhat theatrically, and a little bit performatively—which doesn’t mean it’s not real.

I started writing this when I was about a year into transition. It was relatively early in my experience. This book was me imagining what it would be like to fall in love as a trans person, and to write about trans people tearing things down—being exciting and desirable and in a position to learn fascinating things about themselves that they didn’t know, because they didn’t have bodies before they were 35. And I think it’s a rare exception for me, in that it really is just about two crazy kids in love, by which I mean literally two 40-year-olds in love.

CK: Two 40-year-olds at a rejuvenated part of their lives, though.

IF: Two 40-year-olds who are having experiences that a lot of people have when they’re 19, but they for various reasons have not had yet.

CK: This is the first book that you are publishing since transitioning. Has the process of either writing this book or putting it out there been different for you because of that?

IF: I have a really bad habit of reading my Goodreads reviews. I shouldn’t do it, I’m always going to stop tomorrow. It’s bad. But there is a review of my first book on Goodreads where the headline is something like: “Lyrical and a bit remote.”

This book was me imagining what it would be like to fall in love as a trans person, and to write about trans people tearing things down.

It’s so accurate. That person really nailed what’s going on with it. A lot of my pre-transition work was lyrical and a bit remote. It’s dissociative. It’s disembodied. It’s imagining people as theoretical, like “If I was a person who felt at home in my life, what would I feel like?”

That was the question that my writing was asking before then, which is part of the reason that it has gotten better since I transitioned—because now I can write from the actual perspective of somebody who, in a flawed, confusing way, does have more of a connection to my life and feels more grounded.

CK: Last one, going back to the romance aspect: Which is the nastiest sex scene in the book?

IF: The movie theater one. It’s the most gratuitous. The others have a role—this one has a role too, in that it’s about Sol bottoming for the first time. He is a service top throughout the book, mostly, but in this particular scene he realizes that he feels safe, just being touched and admired and all of the attention is on him, as opposed to all of the attention being on Elsie, his partner.

Sorry, I’ve just convinced myself that it does actually have an important role. But to me, it’s the nastiest because it is the most vulnerable for him and for me, and also because it’s a physically gross scene. They’re having sex in this abandoned room. I have OCD. That is not cool for me. But I really pushed through it, and I push through it for a reason, which is that my characters deserve to fuck all the time.

CK: Why didn’t you include Dracula? He’s in the public domain.

IF:[Isaac did not dignify this with a response.]