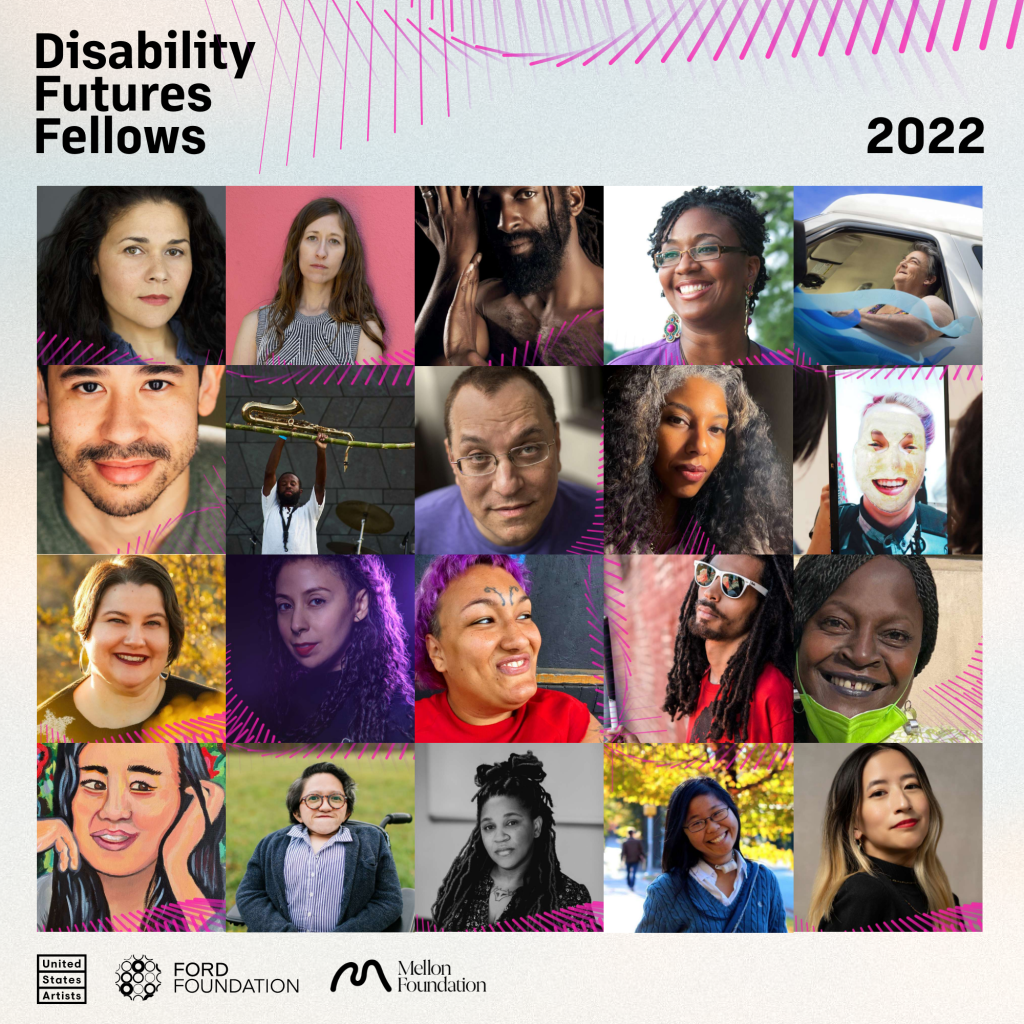

As an editor and writer working in an industry that has historically failed to integrate (or even acknowledge) disability experiences, I was thrilled to receive an announcement that the Ford and Mellon Foundation had selected this year’s recipients of the only national fellowship devoted to supporting disabled artists.

The Disability Futures Fellowship supports twenty disabled creative practitioners whose work advances the cultural landscape. Each fellowship includes an unrestricted $50,000 grant, totaling $1 million for the cohort overall. Now in its second round, the initiative addresses field-wide problems in arts and culture, journalism, and documentary film, including: a dearth of disability visibility in the cultural sector, lack of professional development opportunities accessible to disabled practitioners, and the unique financial challenges facing disabled artists and creative professionals.

Of course, one initiative is far from enough in terms of addressing the serious inequities and access barriers that disabled artists face on a systemic level. That said, Disability Futures is a glorious example of one step in a promising direction. This year’s cohort of Disability Futures Fellows includes a number of talented writers, four of whom—Kenny Fries, Wendy Lu, Naomi Ortiz, and Khadijah Queen—generously agreed to answer my questions about their creative lives and work, and how both are influenced and augmented by disability.

Wynter K Miller: Can you describe your personal journey toward becoming an artist and how that journey was influenced by disability?

Kenny Fries: I started my journey as a playwright but always wrote poetry. In the late 1980s, I started writing poems directly about/from my disability experience. These poems, as well as my poem sequence about the early days of HIV/AIDS, The Healing Notebooks, became the foundation of my first full collection, Anesthesia. It was then that an editor who couldn’t publish poetry asked if I would be interested in writing a memoir. I did. A different editor acquired and published Body, Remember in a two-book deal with Staring Back: The Disability Experience from the Inside Out, the first US multi-genre anthology of disabled writers writing about disability, which I edited … I’ve been writing creative nonfiction ever since.

Wendy Lu: I can’t remember a moment in my life when I did not want to be a writer. I wrote a little bit about disability in college, but I was still figuring things out and had a lot to learn. For my graduate school project, I spent months developing a photo essay and writing an accompanying article about what navigating the dating world is like for women with muscular dystrophy. That project eventually got published in the New York Times in 2016. It was my first byline there, and one of my first major stories about disability. I’ll never forget the day that it appeared in print.

After graduate school, during a fellowship at Bustle.com, I started writing about disability more regularly. My editor knew that I had an interest in disability issues and asked (in a low-pressure kind of way) if I wanted to write about my own disability. I started writing essays and articles about the intersection of disability and a variety of topics—education, health care, entertainment, etc. I covered disability from many different angles based on what was going on in the news; in doing so, I carved out a disability beat for myself. The stories I wrote about disability often got some of the most traction, and I received responses from disabled readers who finally felt like their issues and experiences were being represented in the media. This showed me two things: one, disability is a vastly underreported area, and two, there is a significant audience for stories about disability (and how could there not be, given that around a quarter of the US population has a disability?). By failing to cover disability adequately, media outlets miss so many important stories and leave so many readers and viewers behind. I’m determined to help change that.

After my fellowship, and like many people with disabilities, I faced obstacles during the job-hunt process. Sometimes I would think, “So I’m good enough to speak at this huge national event about my journalism for free, but not good enough to hire for a full-time job?” Finally, I joined HuffPost as an editor in 2018. Aside from editing, I did a lot of disability reporting, I helped shape the newsroom’s style and standards (mostly on disability coverage, but on other topics, too), and I started giving trainings to different newsrooms and journalism organizations. I pursued more ambitious reporting projects, including a package on Disability Pride Month and a big story on the discrimination doctors with disabilities face in the world of medicine. I was really fortunate to work at a newsroom that saw my disability as an asset and with colleagues who embraced me for who I was—that should be the norm, but it’s not. And it’s true: Being disabled has only ever made me a strong reporter and editor.

Being disabled has only ever made me a strong reporter and editor.

Now I’m at the New York Times, and it really feels like things have come full circle. The Times is where I published my first story on disability in 2016, and I’ve learned so much since then. I continue to learn every day.

Naomi Ortiz: As a disabled child, my body was immobilized due to casting. I felt sometimes like an anchor in a chaotic sea of children running and playing around me. I spent my time observing ants crawling across the pavement, sun rays streaming through clouds, and how plants were thriving or dying on the playground. Staying in one spot made me more accessible to listen and talk with other kids. At a very early age I was learning about human nature—violence, pain, joy, kindness, and power dynamics—from these conversations. As soon as I had words, I began making up poetry to process what I was witnessing. I think the sensitivity I bring to my writing, poetry, and visual art was chiseled and shaped by the gift of being in one spot for long periods of time. Disability has offered me an opportunity to really develop relationships with particular physical places, and with people who share their inner lives.

WKM: On a systemic or industry level, what are the biggest challenges you face as a disabled artist working in the United States? Are there issues or areas that you see as critical to address in terms of improving the status quo?

KF: In order for disability to become de rigueur in publishing there need to be so-called “gatekeepers” who are disabled and who also have a stake in disability culture. Also, having intersectional identities, as I do, makes it more difficult for publishers to figure out how to market my kind of work. The disability experience often calls for new forms that don’t follow the predictable narrative of overcoming one’s disability. My work is hybrid, increasingly based on extensive research while not leaving behind my personal experiences.

NO: Anticipating and valuing difference would radically reshape the participation of disabled artists/writers in the arts. For the industry to anticipate that people move differently through spaces, require interpreters, or even need opportunities to take breaks from stimulation during events, would mean the construction of much more open and accessible performances, festivals, readings, etc. Announcing that an event, or that an opportunity, is open to anyone, doesn’t mean that it is. It takes learning about access, anticipating that a lot of folks in any given community need disability accommodations, and then valuing the contributions of disabled folks, in order to pull off a true community event.

In Arizona and the US/Mexico borderlands, arts are under-resourced overall, which ensures that most arts spaces are inaccessible. I wonder how many other disabled poets are unable to read at open mic events or show their work in local galleries because of access barriers? We need better exposure to art created by disabled people, especially those who are also undocumented, queer, young parents, etc., because the lens they are offering contributes to conversations the rest of the country needs to engage with.

It’s frustrating to note that the obvious barriers are still extremely problematic and segregate disabled artists. However, a more subtle barrier that I come across often is pacing. There’s a pace tied to professionalism that is extremely fast. Last week I got an invitation to be on public radio and because I responded six hours after the invitation came in, I missed out. Typing is an extremely laborious process for me due to the technology I use. It doesn’t mesh well with social media. There’s a very ableist assumption that if you care about your work, and sharing it with others, then you are constantly connected and available via email and social media. I produce deep and thoughtful work that is grown from a pace that is slower and intentional. I would love for that kind of professionalism to be respected.

There’s a very ableist assumption that if you care about your work, and sharing it with others, then you are constantly connected and available via email and social media.

Khadijah Queen: I think for neurodivergent folks, it can be difficult to do the kind of networking required of people in creative fields. Another challenge is applying for grants and other funding. The forms required are onerous, often inaccessible, and difficult to customize or tailor when it comes to communication about the work. Hard deadlines, while I realize they serve an important purpose, aren’t always compatible with certain disabilities.

WKM: Could you share more about current/upcoming projects you are particularly excited about, and/or your artistic goals for the future?

KF: My next book Stumbling over History: Disability and the Holocaust is about Aktion T4, the Nazi program that mass murdered disabled people. Excerpts from the book have appeared in the New York Times, the Believer, and Craft, and also serve as the foundation for my video series, What Happened Here in the Summer of 1940?

I’m currently curating Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer, the first international exhibit on queer/disability history, activism, and culture, which opened at the Schwules Museum Berlin on September 1, 2022 and runs through the end of January 2023.

I’m finishing a three-year project, Disability Futures in the Arts, a series of fifteen essays I curated, edited, and introduced, published by Wordgathering. I’m in the midst of editing the third and final cohort (funding was part of a three-year multi-project grant). The fifteen essays span a diverse array of disabilities, media, and nationalities. The final cohort will be published in December.

And I’ll soon be collaborating with fellow Disability Futures fellow Alison O’Daniel on a film based on my poem sequence In the Gardens of Japan.

KQ: I’ve almost completed a longtime prose project, am in contract negotiations regarding a book of criticism, and am slowly fleshing out a collection of travel essays. I’m going to Kenya in December—it’ll be my first trip to Africa, and my excitement level is in the stratosphere.

NO: Over the past ten years especially, I’ve noticed a lot of changes within the ecosystem, and yet, when I’ve looked for art or writing that speaks to the experience of climate change or climate grief, I’m often confronted with extremely ableist analyses. The problem of climate change is often defined as sickness or disability, and the answer as restoration or cure. The solutions presented are uniform, like going zero waste, with an assumption that it can work for everyone. But, for example, I am a disabled person in need of plastic cups. I am also an environmentalist who is concerned about the overwhelming plastic in our ecosystems. In my new book, Rituals for Climate Change: A Crip Struggle for Ecojustice (forthcoming from Punctum Press in 2023), I explore how climate change impacts my relationship with place, expands on and complicates who is seen as an environmentalist, and reimagines what being in relationship with land can look like.

I researched my first book, Sustaining Spirit: Self-Care for Social Justice, because I was curious if self-care could be one tool for the activist communities I was part of (and also excluded from) to build creative capacity. Sustaining Spirit was the book I needed to address burnout when I was working within social justice movements. I feel the same way about Rituals for Climate Change. It’s the book I couldn’t find about the difficult and often unanswerable questions posed by climate change in the US/Mexico borderlands.

WKM: Who are the disabled artists you most admire or that most influence your own work?

KF: For me, Adrienne Rich was the most influential disabled writer. I ‘outed’ her as disabled by including her work in Staring Back, which led to a wonderful correspondence, which I wrote about when she died. Today, I look to my long time comrade Anne Finger, an inventive and important writer of both fiction and creative nonfiction. I will sorely miss Susan R Nussbaum, who died recently. Susan was one of the sharpest, and funniest, writers. Her plays, such as No One As Nasty, and her novel Good Kings Bad Kings, are must reads.

WL: There are so many great disabled journalists who are doing similar work and whom I admire. At HuffPost, I worked with Elyse Wanshel to train reporters and editors to cover disability issues with accuracy, respect, and sensitivity. Cara Reedy does a lot of disability reporting trainings as well. Sara Luterman has done significant reporting on disability and caregiving at the 19th (as well as many other places). Eric Garcia at the Independent knows so much about disability politics and policy. Read Keah Brown on anything related to pop culture and the intersection of disability and Black identity. Amanda Morris, who was the inaugural disability fellow at the Times and now works as a disability reporter at the Washington Post, has written so many fantastic stories across the disability beat. I also want to shout out journalists focusing on disability locally—people like Emyle Watkins, who leads the disability desk at WBFO, and Hannah Wise, who is a regional audience editor at McClatchy and who developed a toolkit for making news accessible. I’ve learned a lot from all of them. Following their careers and their work makes me feel less alone and motivates me to keep going.

NO: Finding other disabled poets and visual artists has taken a lot of work. A lot of big poetry or art databases don’t have search terms for “disabled” or “disability.” I came to disability culture more through nonfiction. Harriet McBryde Johnson’s book, Too Late to Die Young: Nearly True Tales from a Life and Beyond Ramps: Disability at the End of the Social Contract by Marta Russell were some of the first books I read from a disability perspective. Then there were artists I was reading that I didn’t know were disabled, like Audre Lord and Gloria Anzaldúa. Work by poets such as Meg Day, Laura Hershey, and Stacey Park Milbern is deeply moving and encouraging.

No one makes art truly alone. Most of the poets and visual artists who influence me have been my peers—people I found through political organizing who are also artists. My friend Rachel Scoggins is an amazing multimedia visual artist. After seeing her work, I’m inspired to dig deeper in the creation of my visual art. I met Marlin Thomas when I was eighteen and we spent years sharing our poetry with each other and co-writing pieces. When I came across a fellowship for disabled poets, Zoeglossia, I gained life-changing access to a community of disabled artists. I love work like Stephanie Heit’s new book, Psych Murders, which talks about living with psychiatric disability versus a forced narrative of overcoming or resolution wherein disability disappears. Contemporary disabled artists are claiming disability in a beautiful and powerful way.

Additionally, my cultural communities don’t often get a chance to hang out and be featured together. There’s an upcoming issue from Apogee that is a collection of Latinx disabled poets that I’m really excited about.

KQ: Alice Wong comes to mind; Lydia XZ Brown, whose blog post (about using more imagination in our language so that we can stop relying on cliché and ableist metaphors and phrases) I teach in all of my classes; Octavia E Butler; Morgan Parker; L Lamar Wilson; Douglas Kearney; Sheila Black; The Cyborg Jillian Weise was very generous in inviting me to spaces where disabled folks are the majority, and providing a model for being disabled out loud, unapologetic, doing the often-thankless work of demanding that public spaces provide access. Henry Winkler, with those Hank Zipzer books I read to my son when he was in elementary school.

There are also many poets and writers whose work influences me greatly, whose friendship means a great deal to me, and who do not feel comfortable identifying publicly as disabled. I want to acknowledge that the stigma still exists, persists, and causes stress and unnecessary harm.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Sir Lewis Hamilton, the world champion Formula One driver, who has gone on record saying he has dyslexia and ADHD. As I’ve struggled to adjust to my ADHD diagnosis, which came just last year, I’ve tried to incorporate his dynamic approach to social difficulty and professional challenges into my own toolkit. He responds with such grace, power, and refusal to surrender to bullying or despair, in fact surpassing himself in class, influence and achievement. Some might say he’s not an artist but I disagree; he’s a musician, protecting that part of himself for the most part, like I do with visual art. He’s collaborated with fashion designers, worked on films, and even started a special commission to help make Formula One more accessible behind the scenes for young people who’ve been historically underrepresented in the sport both in the car and behind the scenes in the factory. Definitely a creative person to admire and emulate.

WKM: What advice would you give to other disabled artists working in your medium?

Find your community, whether they be writers or not writers. Take risks. Scare yourself with your work.

KF: Know your literary and other creative ancestors. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel, so to say. You are part of a long lineage of disabled writers and artists, many of whom are still alive. Find your role models, whether from the past or present. Find your community, whether they be writers or not writers. Take risks. Scare yourself with your work.

WL: Find people in your workplace who care about the same things you do, who want to improve disability coverage and the overall news industry. Ask if your company has a disability ERG, or maybe even start one yourself. If you’re a freelancer or otherwise work solo, there are a lot of resources (National Center on Disability and Journalism, for instance) and ways to connect with other journalists online. (Don’t know any other disabled writers? Check out DisabledWriters.com.)

I tend to hear from a lot of disabled students who want to become journalists, including people who are switching careers later in life. I often tell them that even though there’s a lot of pressure and expectations around getting the perfect job right after school, so many people do not follow a linear path. (I worked in recruiting before I went to journalism school.) Take whatever time you need to prepare for your next step, and it’s OK to veer off if you need to help pay the bills, take care of family, take care of yourself, etc.

Recognize that there’s always room to learn and grow. Just because I am disabled doesn’t mean I know what it’s like to have every other disability. Be open to being surprised, and report and edit with empathy.

Believe in yourself! Don’t say no to yourself before someone else tells you no. There are already so many barriers for disabled people working in journalism; don’t let yourself be one of them. Set boundaries for yourself. Don’t be afraid to ask for what you need, whether it’s a higher fee for a freelance article or a mental health day at work. Learn to say no if you can. And if you’re not in a situation that’s ideal, start to take baby steps toward finding something better. And then, if and when you’re in a position to do so, pay it forward.

NO: We live in this fascinating reality where it often feels like something doesn’t exist unless it’s been documented online. Sharing art through social media and other online platforms can be an amazing way to share one’s work and to create connections with other artists. However, it can also draw us into a state of comparison. There are artists I follow who produce and post amazing work every few days. I love being able to engage in their art but sometimes it also can make me feel insecure about going so much slower.

Advice that I give other disabled artists is to really take time to engage with and value your own work. This may or may not mean taking some time away from the online worlds we’re part of. I swap work for feedback with several disabled and nondisabled artists/writers. One of the gifts from these kinds of relationships is having someone deeply engage with a poem, an essay, or visual art piece that I’m in the midst of. It’s an opportunity to talk through my process and where I’m struggling. I’m also offering them that same support. I think having a deeper relationship with my work, sharing in slow and meaningful ways with others, helps me to not be so attached to how many “likes” I get. It makes my work more meaningful to me.