For our fourth annual Future of Fashion package, we look at both sides of the fashion-in-2023 coin: AI’s uneasy promises of innovation and a global group of designers who are harnessing the power of traditional craft. Plus, we take a look at the up-and-coming, category-defying talents reshaping menswear.

Makers Versus the Machines

In an uneasy age of article intelligence, some designers have returned to time-tested methods.

Her hair woven into thin blonde braids, her face a sultry scowl, the model sported a cream sweater interwoven with waterfalls of yarn in Rainbow Brite-esque colors. The look was a clear offshoot of fashion’s current DIY/craft movement, and you could easily imagine a downtown It girl like Ella Emhoff sporting the knitwear, which was paired with high-waisted leather shorts.

The only wrinkle: neither the model, nor the sweater, nor the runway, was real. All were AI creations of the Kazakh designer Alena Stepanova, as presented at AI Fashion Week, held in April at New York’s Spring Studios—the image as pie-in-the-sky as the Balenciaga puffer-clad Pope Francis that construction worker Pablo Xavier created when, according to the artist, he was tripping on shrooms.

The event did replicate some real-world biases, though. Business of Fashion reported that “with a few exceptions, the AI models were mostly the thin, high-cheekboned types that dominate runways today.” Outside the venue, designer Ravi Singh protested the lack of racial diversity and disability representation on the show’s virtual runway. Brands that have opted to use AI models, rather than a diverse group of human models, have also come under fire lately, both for creating a phenomenon that Phil Fersht, founder, chief analyst, and CEO of the analyst firm HFS, deemed “artificial diversity” in New York magazine, and because of the employment threat the technology poses for models.

Still, some are embracing generative AI’s possibilities for fashion wholeheartedly. A McKinsey & Company report from March estimated that in the next three to five years, the technology could add between $150 and $275 billion to the fashion, apparel, and luxury sectors. In May, Google announced it would test a search experience for shoppers that uses generative AI, and Farfetch has a partnership with Microsoft to develop luxury applications. Fashable, a generative AI startup, responds to trends and creates designs in keeping with them, while the design platform Cala allows users to incorporate DALL-E technology to create visuals from text descriptions. Finding clothes made to your exact specifications, or designing your own, could soon be accomplished in a few keystrokes.

But as Hollywood writers strike, their demands including protection from AI taking over their job responsibilities, and as the “godfather of AI” himself, Geoffrey Hinton, sounds the alarm in the New York Times about the technology’s negative implications for society, fashion has reasons to be concerned, too. For an industry that celebrates individualism and creativity, and in which the profit margins for young designers are already slim, the rise of the robots brings with it some fearsome implications.

Which is why, for our fourth annual Future of Fashion package, we wanted to take futurism in a less expected direction. Rather than lines of code, hands and minds are the technologies we’re celebrating here—including those of the designers in the following pages, who have harnessed the craft traditions of their native countries and turned them into wearable art. At least for now, that kind of spark is something that’s impossible to replace.—Véronique Hyland

New Designers to Watch

Lagos, Nigeria, and London

“I’m a storyteller,” says Faith Oluwajimi, the Nigerian founder and creative director of the unisex brand Bloke. “My medium just happens to be clothes.”

Born in Ijebu Ode, a town in Ogun State, the self-taught designer was already honing his stylistic eye as a child. His mother spotted a glimmer of creativity in him and would seek his opinions on her outfits. “She would ask, ‘Faith, what do you think? Does this fit look good?’” he recalls. “And I’d be like, ‘Hmm, I think you should change the shoes.’ She must have noticed something [in me] for her to trust my judgment.”

At only 19, Oluwajimi founded Bloke, his “artisanal, genderless” fashion brand. Like most teenagers, he was on a path of self-discovery. “I was trying to find that intrinsic value that makes me, me,” he says. “I also wanted to explore what it was like to make garments without any construct or bias of gender.” The garments are ethically and sustainably created: His knitwear is made from organic yarn, and he upcycles coconut shells to use as buttons.

Not only do Nigeria’s raw materials serve as inspiration, but so, too, do its politics. Bloke’s fall 2023 collection was titled “Black Tax,” the term for the money that Black professionals provide to their families in need, often out of obligation. “It was something that I could relate to as a Black [and African] person,” he says. “If these issues weren’t in the picture, then Africans would have a chance of accumulating wealth like their white counterparts,” he explains.

One immediately eye-catching look is a pantsuit whose olive-green tones are contrasted with black colorblocking. “Green means there’s some growth there,” he says. “There’s prosperity. And of course, money’s green.” Black serves as a juxtaposition to this fertile utopia. “It’s me trying to remind people that [the Black Tax] is still happening. These are the things that have been pushing people down.”

Oluwajimi’s thoughtful work has garnered global attention. This year, Bloke was

a semifinalist for the LVMH Prize. Though Oluwajimi was honored by the recognition—he was the only African to appear on the list—he doesn’t dwell on it. “It’s nice to see the increased progression. But I don’t feel like, ‘Yeah, I’ve done some amazing things,’ because, okay, we did it, but then what’s next?” He hopes that his accomplishments reach far beyond him and inspire other Nigerian creatives. He wants to show people that “it’s possible to do things like this from places like this.”—Juliana Ukiomogbe

Santiago, Chile and London

What do your feelings look like? Stephanie Uhart’s look like “fluffs”—cloudlike knits in soft pastels or bold hues, arranged into abstract gowns, skirts, or handbags. Her signature floor-length pieces, which can take days to make by hand, look like an avalanche of fuzz cascading off the wearer.

The idea started during the beginning of the pandemic, when Uhart, like many of

us, was “going through all my emotions.” It was her final year at Central Saint Martins, she was living alone in London, and the COVID era amplified her feelings of isolation. When her tutor suggested, “Why don’t you draw your feelings?,” Uhart responded with illustrations of random shapes. “This is how loneliness looks to me,” she remembers

thinking. You just wouldn’t guess it from the whimsical, candy-colored finished products.

“They look very fun and colorful, and I was like, well, I was wildly depressed,” she says, half-joking. But the clothes are meant to be comforting, “kind of like a hug.”

Growing up as the child of two art dealers in Chile, Uhart gravitated to both art and fashion. She even spent a few years in business school, to her parents’ disappointment, before applying to CSM—and getting in on the third try. Since Uhart graduated in 2020, her pieces have been worn by stars like Arca and Chloe Bailey, and have gained traction on social media. (When she’s feeling down, she double-checks that SZA is still following her on Instagram for a mood boost.)

Like her designs, Uhart’s process is free-flowing and intuitive. She doesn’t start with a sketch or toile; whatever she’s working on is the final piece. “I try to not make mistakes. But that’s impossible,” she admits. There are no rules about who can wear her clothes, either. She doesn’t define it as womenswear or menswear—she doesn’t even use specific sizes. “I didn’t feel I could wear a lot of the fashion that I liked growing up, so I want this to be very inclusive,” she explains. But her mantra is simple: “Some people hate it, but if you like it, it’s for you.”—Erica Gonzales

Kingston, Jamaica and New York

What does the dancehall girl wear when she grows up? Rachel Scott is weaving the answer for Jamaican women—and all those who retired from “hot girl summer”—with her line Diotima. Founded in 2021, the brand was more than 20 years in the making, and the Jamaican-born designer eventually left her post as vice president of design at Rachel Comey to focus on it full-time. Scott studied art and French at Colgate University, and took classes at Central Saint Martins and FIT, and later at Milan’s Istituto Marangoni. But it was an internship at Milan-based brand Costume National that was “the best school,” she says. “That’s where my obsession with tailoring comes from.” (She later became an assistant designer at the label.) Scott’s enthusiasm for craft, paired with the design standards of Italy, provided the template for her line, which honors Jamaican artisanship and was a finalist for this year’s LVMH Prize.

Scott returned to her home country and began exploring the handmade designs of local craftswomen, created mainly for tourists. Traveling the winding roads of Jamaica’s north coast, she learned about hardanger embroidery, a centuries-old technique in which artisans “pull threads and then embroider around it,” Scott explains. Women there were also skillfully crocheting doilies, tablecloths, and even bedspreads—and Scott knew that in time, she wanted to incorporate these crafts into her designs. But she feared that the Jamaican space was saturated, and there was no room for her brand. Then came a complete change of heart. “That [thinking] is what limits us,” she says. “We need the multiplicity of voices and expressions of who we are.”

In 2019, at the craft market in downtown Kingston, Scott met a Jamaican crochet artisan named Helena, whom she refers to as “her second mother.” Helena had a shop in Kingston selling her designs and other crafts, but it is now manned by somebody else, Scott says, “because she’s fully working with me.” Jamaica is heavily reliant on tourism, an industry responsible for over 30 percent of the country’s GDP and a third of its jobs, according to a report from the World Bank. The pandemic halted tourist traffic, cutting off income for many. “I don’t have money, but I have ideas,” Scott told herself. “Maybe we can start developing something, and we’ll see where it goes.”

Not only did it go, but it grew. What began as sending photos of designs back and forth with Helena and another woman evolved to Scott supporting a small cooperative of a dozen women who handcraft many of her designs. She runs her fingers over the crochet interwoven into her smartly tailored blazer, saying, “I’m aesthetically drawn to it. But also, politically, I’m drawn to this form of making.” Crochet can’t be made by machine; it’s all made by hand. Her cooperative includes women from all corners of the island, some holding jobs by day and crocheting for Scott at night. Back in New York, Scott works with patternmakers and factories in the Garment District to produce the line.

Slow fashion is something she strongly believes in. “It’s having a respect for handmade and a time frame that you can’t speed up.” And she doesn’t want to design excessively. “I don’t want to be one of these brands that blow up and lose focus on the foundation of what I’m trying to do, which is Jamaica,” Scott says. Although she admits her brand is not yet profitable, Scott is helping her small cooperative build wealth in the land she calls home.

“I don’t like to talk about this because I get kind of shy, but Helena once told my mother, ‘Rachel doesn’t realize how many people she’s feeding,’” she says. “I was blown away.” Brain drain happens when talented people migrate and never return; everything gets exported—the knowledge, the intelligence, the dollars. Scott is bringing her design intelligence back home through Diotima, one stitch at a time.—Danielle James

Dublin

“Dying / Is an art, like everything else,” says Sylvia Plath’s poetic heroine Lady Lazarus. It might seem like a morbid starting point, but in the hands of Irish designer Róisín Pierce, those macabre lines were transformed into a series of ethereal looks in Pierce’s signature all-white palette that felt like sartorial whipped cream.

Pierce has been obsessed with Plath since her midteens, but became particularly interested in her when researching Ireland’s Committee on Evil Literature, which banned works by Plath and Edna O’Brien, as well as “feminist journals and information on reproductive [care].” She sees Plath’s poem, also called “Lady Lazarus,” as “almost a women’s anthem. With each stanza, she becomes more and more powerful.” The poem’s reference to shrouds, in particular, struck her. That led her to research the way that Victorian women would make their own shrouds for their bridal trousseaux, “in preparation for potential death in childbirth”—a historical footnote that gives her frothy, innocent dresses a sinister edge.

It’s not the first time Pierce has confronted the uglier parts of Ireland’s history. Her first collection was inspired by the clothing made at the Magdalene Laundries, forced-work institutions for so-called fallen women that persisted until the 1990s. Pierce’s lacework and embroidery drew on the techniques used there, and she tied the inspiration to the Repeal the Eighth movement, which successfully overturned the country’s abortion ban in 2018.

Pierce has always been fascinated by the twinned histories of craft and women’s rights in her country. When it comes to craft, she says, “I try to analyze: Is it liberating or is it suppressive?” She incorporates traditional Irish lace—once known as “relief lace,” as it helped lift the country out of the economic depression caused by the potato famine. Pierce prefers to call it “hope lace,” because craft “has the potential to take people out of negative situations.” To keep that flame alive, she has been training younger artisans in textile techniques that have been slowly dying out.

Centuries of heritage aside, Pierce’s zero-waste approach feels distinctly contemporary. She creates her shapes out of strips and squares of fabric, transforming them into 3D patterns. Working in mostly white highlights the texture, “so you see little intricacies.” And despite making her Paris debut this past season, she’s perfectly happy being based in Dublin, far from fashion’s madding crowd. “It allows for a clear head,” she says.—Véronique Hyland

Milan

Des_Phemmes designer Salvo Rizza makes clothes that are meant to be lived in. It’s understandable, then, that when contemplating the look of his brand, he referenced those around him. “It’s a love letter to the women in my life,” says the Modica, Italy, native. “There’s an attitude when they wear something they like. [I’m drawn] to that sense of empowerment.” (Apparently, so is Dua Lipa, who’s a fan.)

Rizza wants to commemorate “the good and the bad” in his designs; he cites a red leather Prada dress, which a friend wore the night her boyfriend broke up with her, as the starting point for a recent collection. “I wanted to take a sad memory and transform it into something positive,” he says.

Launching a going-out label in March 2020 was challenging, to say the least. “The timing couldn’t have been worse,” Rizza admits. But as soon as lockdown was over, there was a paradigm shift: Everyone wanted to get dressed up again. “I don’t like the idea of my clients buying something and wearing it once because they don’t want to destroy it,” he says. “You need to collect more memories when you wear it.” And if you get dumped, so be it—at least you’ll have a pretty dress.—Claire Stern

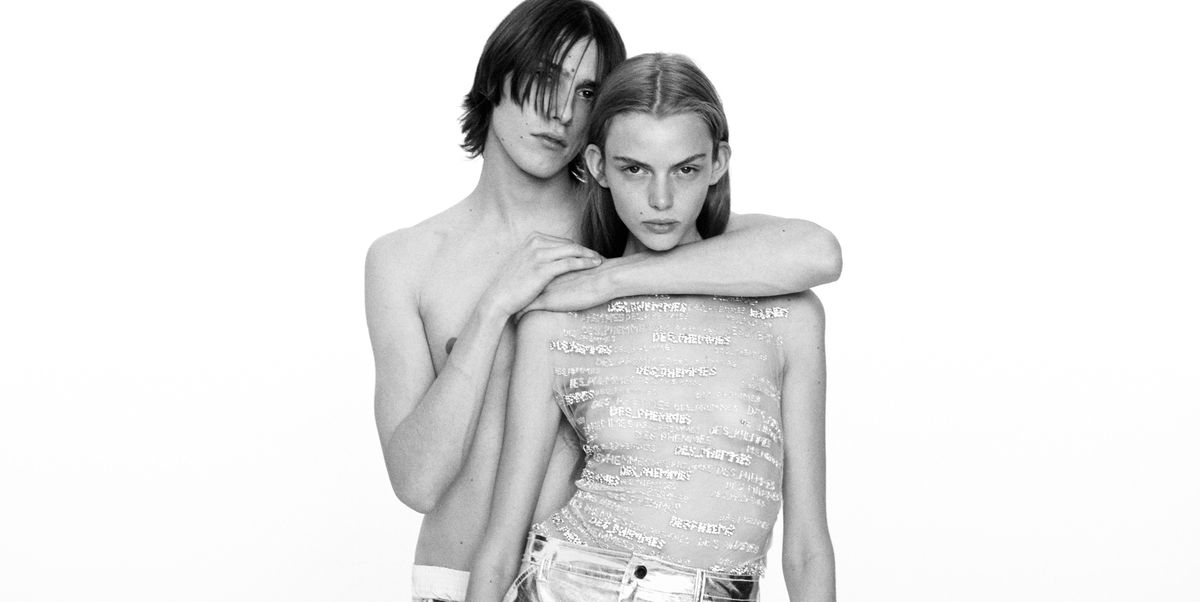

Menswear Has Never Been More Exciting

Today’s designers care less about the gender binary and more about experimentation.

When I hop on the phone with Willy Chavarria, the acclaimed menswear designer rocking New York City with his audacious glamour, I’m surprised to hear that about 35 percent of his clients identify as female. “Gender identity is something to just enjoy and have fun with,” he says. “[My] collections are designed for anyone to wear.”

Increasingly, menswear designers are catering to people across the gender spectrum looking for innovative designs that don’t fall on one side of the binary. The movement parallels the increase in womenswear designers translating their clothing for male-identifying customers, with recent entrants including Simone Rocha and Chopova Lowena.

Since starting his brand LGN in 2017, Paris-based Louis-Gabriel Nouchi has placed an emphasis on dressing every body—male, female, and otherwise—to critical and commercial acclaim. His inspiration often comes from books he loves; his most recent show was based on Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho and featured stars such as Lucas Bravo from Emily in Paris alongside anonymes, or anonymous customers. Luxe jersey knitwear, shirting, and separates are Nouchi’s bread and butter, and his tailoring embodies corsetry without its usual constriction. For Nouchi, design is “about the garment itself and…how society [perceives] how men are dressed, how they’re allowed to dress, what is accepted, what is considered too niche.” People of varying body types, genders, and sizes can see themselves in his designs, providing what he calls a “safety zone” to experiment comfortably. Nouchi considers menswear to be a “laboratory,” offering myriad ways to get dressed.

Another designer considering every body is Chavarria, who has long understood the need for comfortable menswear that doesn’t sacrifice capital-F fashion. “It’s more important to have a range of fit that actually flatters and makes people feel good,” he says. With his last two collections, he has taken his vision to another level, reworking classic American workwear pieces into beautiful high fashion. “So little of [style] is about what you wear, and so much of it is about how you wear it,” he says. “Clothes are such a fundamentally important part of how we design ourselves….I’ve always looked at the people as being just as important as the clothing.” Ultimately, he sees gender binaries as tools of exploration for embracing what works and rejecting what doesn’t. “I think masculinity and femininity are still very attractive,” he says. “For me, it’s not about getting rid of them for being ‘toxic.’ It’s about playing with them, overlapping them, and having fun with them.”

A constant with menswear designers today is not intentionally creating unisex clothing, but rather acting on a feeling—and, as Chris Leba of R13 puts it, “dressing for the times.” Leba has been crafting his luxe-punk label since 2009; after cutting his teeth at Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren, he set out to create an Americana brand infused with rock ’n’ roll. He’s added to his usual references of the Sex Pistols and Nirvana to create a line built around individuality, exemplified by his cast of models, who, yes, are mostly female-identifying. But, Leba says, “Our male-identifying customer base loves all aspects of the collection—dresses and skirts included.” The brand is releasing a menswear-specific capsule this September, birthed from Leba’s desire for “really great, high-quality cargoes.” Ultimately, it’s about creating clothes that meet the moment, regardless of category. As Leba says, “Traditional boundaries have been blurred over the years. A great pair of jeans is simply a great pair of jeans.”—Kevin LeBlanc

This story appears in the August 2023 issue of ELLE.