The Ice Pop Lady Rules the Neighborhood

“Flip Lady” by Ladee Hubbard

History:

Raymond Brown hears the sound of laughter. He puts down his book and looks out the window.

Here they come now, children of the ancient ones, the hewers of wood, the cutters of cane barreling down the sidewalk on their Huffys and Schwinns. Little legs pumping over fat rubber tires, brakes squealing as they pull into the drive, standing on tiptoes as they straddle their bikes and stare at the house with their mouths hanging open.

Just like before. Some of them he still recognizes. He made out with that girl’s sister in the seventh grade, played basketball with that boy’s uncle in high school. This one was all right until his brother joined the army, that one was okay until her daddy went to jail. And you see that girl in the back? The chubby one standing by the curb, next to the brand-new Schwinn? She hasn’t been the same since the invasion of Grenada, nine years ago, in 1983.

The Spice Island. When the Marines landed, she was three years old, living in St. George’s near the medical clinic with her mother, the doctor and Aunt Ruby, the nurse. The power went off, the hospital plunging into blue darkness while machine gunfire cackled in the distance like a bag of Jiffy Pop bubbling up on a stove. Oh no, Aunt Ruby said. Just like before.

It’s all there, in the book on his lap. Colonizers fanning out across the Atlantic like a hurricane, not exactly hungry but looking for spice. They claimed the land, they built the plantations, they filled the Americas up with slaves. Sugar kept the workers happy, distracted them from grief. And four hundred years later you have your military invasions and McDonald’s Happy Meals, your Ho Hos and preemptive strikes. Your Oreos and Reaganomics, your Cap’n Crunch.

And Kool-Aid. These kids can’t get enough of it. They sit in the driveway, they shift in their seats, they grip the plastic streamers affixed to their handlebars. One of them kicks a kickstand and steps forward, fingers curled into a small tight fist as he knocks on the kitchen door.

“Flip Lady? You in there?”

Just like before. They roamed the entire earth in search of spice so why not here, why not now?

“Flip Lady? You home? It’s me, Calvin. . . .”

For the past few weeks they’ve been coming almost every day.

Raymond closes the curtain. He shakes his head and turns towards the darkness of the back bedroom. “Mama? It’s those fucking kids again.”

2.

The squeak of old mattress coils, a single bang of a headboard against a bedroom wall. The Flip Lady wills herself upright, sets her feet on the floor, sits on the edge of her bed and stares at the chipped polish on her left big toe. She stands up, reaches for her slippers, straightens out her green housedress, and walks out the bedroom door. The Flip Lady shuffles into the living room where her nineteen-year-old son, Raymond, sits on a low couch, reading. Long brown body hunched forward, elbows resting on his knees as he peers at the page of the book on his lap. In an instant his life flashes through her mind in a series of fractured images, like a VHS tape on rewind. She sees him at sixteen, face hidden behind a comic book, then at seven when his feet barely touched the floor. And before that as a chubby toddler, gripping the cushions with fat meaty fists, laughing as he hoisted himself onto the couch. Without breaking her stride, and for want of anything else to say, she mutters, “I see you reading,” and passes into the kitchen.

The Flip Lady lifts a pickle jar full of loose change from the counter and looks out the kitchen window.

“That you, Calvin?” she says to the little boy standing on her porch.

“Afternoon, ma’am.” Calvin smiles.

She twists the lid off the jar, opens the kitchen door, and squints at the multitude assembled in her backyard.

Calvin plunges his hand into his pants pocket and pulls out a fistful of dimes. He drops them into her jar with a series of empty pings.

“Well, all right then,” the Flip Lady says.

Calvin glances over his shoulder and winks.

She walks towards her refrigerator while Calvin stands in the doorway. He cocks his head and peers past her into the living room. Glass angel figurines and the tea set on the lace doily in the cabinet against the wall; bronzed baby shoes mounted on a wooden plaque; framed high school graduation photos and Sears portraits of her two sons sitting on top of the TV set; a stack of LPs lined up on the floor. A dark green La-Z-Boy recliner and the plaid couch where her younger son sits with a book on his lap. Calvin turns his head again and sees the Flip Lady standing in the middle of her bright yellow kitchen, easing two muffin trays stuffed with Dixie cups out of her freezer.

The Flip Lady studies Calvin’s face as he scoops the cups out of the trays, licking his lips, eyes lit up like birthday candles. She smiles. Her boys were the same way when they were that age, crowding around her back door with all their friends, giddy with excitement as they sucked on her homemade popsicles. She used to hand them out when their friends came over to play after school and on weekends; it was a way to keep them in her backyard where she could watch them from the kitchen window. A good mother, she wanted to get to know how her boys passed their time and with whom. She wanted to memorize their playmates’ faces and study their gestures until she felt confident that she could tell the clever from the calculated, the dreamy-eyed from the dangerous, the quiet from the cruel. She hadn’t done it for money. No one had to thank her, although her neighbors told her many times how much they appreciated her looking out for their children that way.

The Flip Lady frowns. Of course, everything does change, eventually. There comes a time when a mother has to accept that the promise of sugary sweets has lost its ability to soothe all grief. They don’t want your Kool-Aid anymore. They busy, they got other things to do. One day you find yourself standing alone in the kitchen, hand wrapped around a cold cup, melting ice dripping down your fingers as you wonder to yourself when exactly the good little boys standing on your back porch became the big bad men walking out your front door.

She looks at Calvin. “How was school today, son? You studying hard, being a good boy? Doing what your mama tells you?”

“Yes, ma’am.” Calvin walks around, passing out Dixie cups to his friends.

“Well, all right then,” the Flip Lady says.

3.

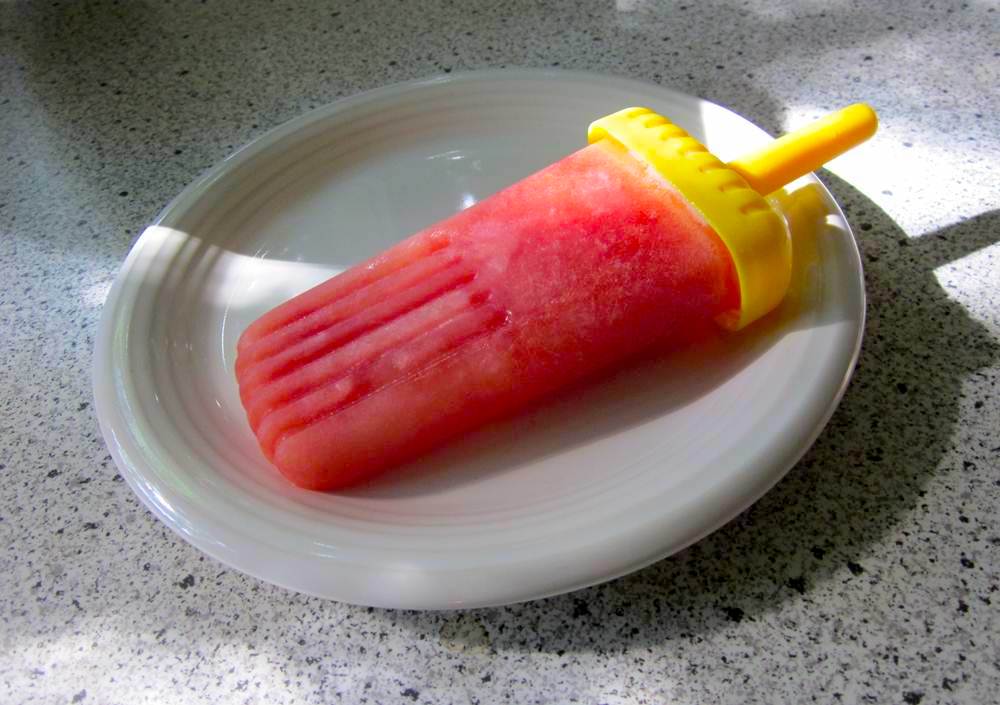

What you get for your money is a hunk of purple ice, a Dixie cup full of frozen Kool-Aid. The girl in the back stares at hers. It’s not quite what she was expecting, given how far they have come to get it. According to the black plastic Casio attached to her left wrist, they’ve been riding for a full twenty minutes in the opposite direction from where she was trying to get to, which was home. One minute she was in the schoolyard unlocking her bike and the next they were standing over her, the whole group of them saying, Come with us. She knew it wasn’t an invitation but an order. They were taking her to wherever it was they went when they sprinted off after class, their laughter echoing in the distance long after they’d disappeared past the school gate. How could she say no? She lifts the cup to her open mouth and runs her tongue along its surface, absorbing flat sweetness and a salty aftertaste.

“It’s just Kool-Aid,” someone says.

The girl closes her mouth. She looks around the parking lot of Byrdie’s Burgers, where they have parked their bikes to eat. Everyone is pushing the bottoms of their cups with the pads of their thumbs, making those sugar lumps rise into the air. They’re tilting their cups to the side and pulling them out, melting Kool-Aid dripping down their hands as they flip them over, then carefully placing them back in the cups, bottom sides up. They’re sucking on their fingers, they’re licking their lips, their mouths pressed against homemade popsicle flips.

“What’s the matter? Don’t they have Kool-Aid where you come from?”

The girl looks down at her cup. She pushes her thumbs against the bottom but presses too hard; the hunk of purple ice pops out too fast and soars over the rim. She tries to catch it, but her hands fumble; it dribbles down the front of her shirt, then lands with a thud on the pavement.

“Now that’s a shame.”

The girl wipes her hands on the front of her shorts, palms already sticky. She blames her upbringing, all those years spent stuck on that rock, how to flip a homemade popsicle was just one more thing she should have known. She got the exact same looks from the kids on Grenada, after she moved there with her mother and Aunt Ruby all those years ago: What you come here for? What you want with this rock, when everybody trying to get off it? As if only white people were supposed to spin in dizzy circles like that, as missionaries or volunteers or tourists on extended leave. She can still see her former playmates in the eyes of her new school’s handful of immigrant kids, with their high-water pants and loud polyester shirts, huddling and whispering to each other as they move down the halls. They look tired, fagged out from the journey, but at least they have an excuse. She’s not even West Indian. Everyone knows her uncle Todd lives right around the block from Henry’s Bar and has been living there for at least twenty years.

“What a waste.”

When her mother said they were moving back to the States she’d been like everyone else she knew, picturing New York or LA like she saw on TV, not some narrow sliver of southern suburbia wedged senselessly in between. Instead she is surrounded by a whole parking lot full of distracted sucking children who don’t like her anyway.

“Go get another one,” someone says. Calvin, the boss around here, although sometimes they take turns.

“It’s only ten cents. Ain’t you even got another dime?”

“What’s the problem? You scared to go back by yourself?”

“What’s the matter? Don’t you want one?”

Of course she wants one. But she wants that one there, already dissolving into a pool of purple ooze at her feet. If she can’t have it then she wants to go home, sit on the couch, eat leftover Entenmann’s cookies from the box, and watch Star Trek reruns until her mother gets home from work at the hospital.

She looks back at the Flip Lady’s house, now halfway down the block. She’s tired of traveling the wrong way, dragging herself in the wrong direction without real rhyme or actual reason. But she also doesn’t want to cause trouble, doesn’t want to make waves. She reaches for the handlebars of her bike.

“Naw, leave it.” They lick their lips and smile. “We’ll watch it for you.”

But they lie: in a few minutes they are going to teach her a lesson about realness, about keeping it. Because even her accent is fake. Because she rides around on a Schwinn that is just like theirs, except it is brand-new.

“Go on, girl.”

Plus, she’s fat.

The girl nods her head. She knows they are going to start talking about her as soon as her back is turned. They’re a mean bunch; she’s seen them do some terrible things at school. She’s already figured out that it does no good to wander in and out of earshot of this group. Either you’ve got to stay knuckle to knuckle, packed tight like a fist, or else give them a wide berth and do all you can to not draw attention to yourself.

She turns around and starts walking. She can hear them whispering and laughing behind her, a hot humid jungle of bad moods circling her footsteps, gathering in strength with each step she takes. A flash of fear tickles her nose, like when you’re swimming and accidentally inhale water. But she does not stop walking, somehow convinced that to turn around midstride will only make things worse.

She knocks on the Flip Lady’s door, expecting to see the kind face of the woman who answered it not a half hour before. Instead it’s a man, dressed in a pair of sweatpants and a blue T-shirt, a little brown Chihuahua shivering in the palm of his left hand. She stares up at flaring nostrils, dark eyes, eyebrows arched.

“What do you want?”

“I dropped mine.”

Raymond shakes his head. “No. I’m not doing this. Mama’s not here. Understand? Flip Lady gone. She went out. Shopping. To buy more Kool-Aid, most likely. So why don’t you just come back tomorrow. . . .”

A harsh peel of laughter cuts across the horizon. The girl puts her head down and reaches into her pocket. She holds out a dime like a peace offering.

Raymond recoils. “I don’t want that. What am I supposed to do with that? Girl, you better just go on home.”

He squints into the distance behind her. “Those your friends? Little heathens . . .”

The girl hears the harsh scrape of metal against concrete as the man steps past her, onto the porch.

“Hey, girl. Is that your bike?”

She winces at the sound of rubber soles pounding on the spokes and stares down at the mat in front of the door.

“Hey, girl . . . What the heck are they doing— ”

She shuts her eyes, feels a stiff pressure in her groin, like a sudden swift kick against her bladder, then a sharp tingling sensation between her legs.

“Hey, girl, turn around. . . .”

The girl looks up. “May I use your bathroom please?”

Raymond looks at the child breathing hard with her thighs clamped together, shifting her weight from side to side. He bites his lip then nods and points down the hall, watches her sprint past his friend Tony, who is standing in the middle of the living room grinning from ear to ear.

“You from Jamaica?” Tony says as the girl rushes past. She runs into the bathroom and slams the door.

Raymond shakes his head. It’s all there, in his book, he thinks. It’s always the weak and the homely who get left behind. Stranded on the back porch, knees shaking as they quiver and dance, thin rivers of pee running down their ashy legs.

4.

The girl sits on the toilet in a pink-tiled bathroom, staring at a stack of Ebony and Newsweek magazines in a brass rack near the sink. She’s thinking about her bike, about how much she’s going to miss it. She’s only had it for a few weeks, but still. It’s something she begged and pleaded for, something she swore she needed to fit in at her new school. Now she doesn’t even want to look at it. A few minutes before the Flip Lady’s son knocked on the door and told her he would fix it so she can ride home, but it’s too late. It’s already ruined. She’s already peed herself and run away.

Everybody’s always so busy running, so busy trying to save their own skins, she remembers her aunt Ruby telling her. That’s what’s wrong with this world. We’ve got to stand together if we’re going to stand at all. The girl had liked the sound of that even if she sensed that it didn’t really apply to her. She’d seen her aunt and mother working in the clinic, stood numb and mystified by the deliberateness with which they thrust themselves into other people’s wounds. Stitching a cut, dressing a burn, giving a shot, connecting an IV. It was intimidating, the steadiness of her mother’s hand sometimes. Even now, in the midst of grief. Like some nights when her mother stomped into the living room and cut off the TV in the middle of the evening news, her voice damming the flood of silence that followed with the simple statement: “They lie.”

The girl reaches for the roll of toilet paper and wipes off the insides of her legs. She pulls up her damp panties and zips her shorts. When she opens the door she finds Tony alone in the living room, crouched down on the floor, peering behind the stack of LPs lined up against the wall.

“You feeling better?”

When she doesn’t say anything, he puts the records back. He stands up, shoves his hands into his pockets, and smiles.

“So, what, you from Jamaica?”

The girl shakes her head. “I come from here.”

“Not talking like that you don’t.” Tony walks past her and then stops. He crosses his arms in front of his chest, puts one hand on his chin and stares down at the couch.

“I lived on Grenada for a time but— ”

“What’s that?”

She watches as he kneels in front of the couch. He lifts the cushion and runs his hand underneath it like he’s looking for spare change.

“Another island,” she says.

He puts the cushion back and sits on top of it, bouncing up and down a few times to force the cushion back into place.

Tony nods. “Y’all smoke a lot of ganja down there too?”

The girl shrugs awkwardly. She wonders what about her appearance might remind this man of a Rastafarian. Rastafarians wore dusty clothes, had calloused feet and thick clumps of matted hair. They sat in the waiting room, making the clinic smell like salt and homemade lye soap. Her mother checked their charts while Aunt Ruby rubbed their arms with cotton pads dipped in alcohol. When they saw the needle, Aunt Ruby smiled and told them it was just a pinprick. Don’t worry, it will be all right, she promised. Just look at me.

But, no, she didn’t smoke a lot of ganja.

“That’s all right,” Tony says. “You still got that sweet accent, huh?” He pulls a bouquet of plastic flowers out of a white vase, peers down inside it, and holds the flowers up to his nose.

“I like things sweet.” Tony puts the flowers back in the vase and reaches underneath the table, running his hand along the wood panels underneath. The girl stares down at the books stacked on top of it. And next to the table is an open cardboard box with still more books tucked inside.

The kitchen door swings open. Raymond walks back into the living room, tossing a wrench onto the table, next to the books.

“How far away you live?” He can already see her starting to blink rapidly. “I mean, I tried. But the body’s all bent. You’re going to have to just carry it or drag it or something, I don’t know. . . .”

“Damn.” Tony shakes his head. “What’s wrong with these fucking kids today? Why you think they so evil?”

Raymond looks at the girl: short, stiff plaits of hair standing up at the back of her neck, dirty white T-shirt with a pink ladybug appliqué stretched across the stomach, plaid shorts, socks spattered with purple Kool-Aid stains. He used to feel sorry for awkward, homely girls like that. But now sometimes he thinks maybe they are really better off. “I tried.”

“Why they do that to you, girl?” Tony says. She just stands there, hands clasped behind her back, swaying from side to side.

“You gonna be all right?” Raymond nods towards the front door. “You want a glass of water or something, before you go?”

“Hey, Ray, man, you remember us? You remember back in the day?”

Raymond shrugs. All he knows is that the girl is not moving. She just stands there staring down at the stack of books on the table.

“I think we were just as bad,” Tony says.

“Let me get you that glass of water.” Raymond disappears into the kitchen. The cabinet squeaks open, followed by the sound of crushed ice crumbling into a glass.

She started making those fucking popsicles again almost as soon as he came back to hold her hand at his brother Sam’s funeral.

“And your mama with them flips,” Tony yells from the living room. “When’d she start up with that again? I haven’t seen those things in years.”

“Well, you’re lucky,” Raymond calls back. Just thinking about all those little kids crowding around his mama’s yard is enough to make him wince. She started making those fucking popsicles again almost as soon as he came back to hold her hand at his brother Sam’s funeral. He’s convinced there is something wrong with it, that it is unhealthy somehow, an unnatural distraction from grief. And look at the kind of hassles it leads to. He puts the glass under the faucet and pours the girl her water. All he wants is to get the child out of his house before she has time to pee herself again.

“When did she start charging people?” Tony asks. Raymond closes his eyes and shuts the water off. He knows Tony doesn’t mean anything by it but, really, that’s the part that bothers him the most, all those jars of fucking dimes. He walks back into the living room.

“Man.” Raymond shakes his head. He hands the girl her water. “I don’t want to talk about fucking Kool-Aid.”

Tony shrugs. He looks at the girl.

“They used to be free.”

5.

There are too many people in the house, Raymond thinks. That’s what the problem is. He can sense that, Tony and the girl filling up the space, making him feel crowded and cramped. For the past five days it’s been just him and the books, the box he found hidden in the back of his brother’s closet. And it shocked him because he’d never actually seen his brother read anything more substantial than a comic book. But he knew they were his brother’s books and that his brother actually read them because he recognized the handwriting scribbled in the margins on almost every page.

The girl lowers her glass and nods her head towards the stack on the table. “Are all those yours?” she asks Raymond.

“Naw.” He shakes his head. “They belong to someone else.”

“Just a little light reading to pass the time, huh, Ray?” Tony says.

He picks up a book and glances down at the cover, assessing its weight. “Looks dry.”

Raymond shuts his eyes. The word “fool” bubbles up in his mind involuntarily, before he can force it back down with guilt. He’s known Tony for twelve years, ever since they both got assigned the same homeroom teacher in the second grade. Somehow, when Raymond went to college, he’d imagined himself missing Tony a lot more than he actually had. He opens his eyes and looks at the girl.

“Why did you ask me that? About the books? I mean, what difference does it make to you who they belong to?”

She points to the one lying open. “I know that one.”

“What do you mean you know it?”

“I mean I’ve seen it. I read it.”

“That thick-ass book?” Tony glances down at it, then back up at the girl. “Naw. Really?”

“Parts of it,” the girl says. “Aunt Ruby gave it to me.”

“Now you see that?” Tony says. “Another one with the books. Now we got two. . . .” He stands up and walks to the kitchen.

Raymond squints at the girl in front of him, rocking slowly from side to side as she drinks her glass of water.

“Look, girl. You’ve been here for almost an hour now. What’s the problem? Don’t you want to go home?” He studies her face. “Are you scared? Worried your daddy is going to beat you or something, for letting them fuck your bike up like that?”

“I don’t have a daddy.”

“Then what is it?”

“It’s the bike.” The girl shakes her head, lower lip popping out in a pout. “I don’t want it.”

“What do you mean you don’t want it?” He winces at the sudden loud clatter of pots and pans being pushed aside in one of his mother’s kitchen drawers.

“You don’t want to take it home?”

The girl nods.

“Well, leave it then. You just go home and I’ll keep it in the garage and you can come back for it later, like when Mama’s here or something.”

A drawer slams shut in the kitchen.

“Hey, man, what are you doing in there?” Raymond yells.

“Where she keep it?”

“What?”

“The Kool-Aid. I’m thirsty.”

Raymond frowns. “I told you she went to the store,” he yells back. “What the fuck is the matter with you?”

Tony steps back into the living room, squints at Ray.

“There is no fucking Kool-Aid in this house,” Raymond says.

“I hear you.” Tony nods. He frowns. “Just relax. Hear me? Don’t lose your cool.”

Tony keeps his eyes locked on Raymond’s as he walks backwards to the kitchen, then disappears behind the door.

Raymond looks at the girl.

“I’m trying to be nice.”

6.

Tony stands in the middle of a bright yellow kitchen, staring at the dimes in the pickle jar on the windowsill, thinking about Raymond losing his cool. Baby brother is clearly not well. Tony could see that as soon as he walked into the house, sensed it just from talking to Ray on the phone. Something about his big brother, Sam, having all those books in his closet really tripped Ray up for some reason. Maybe Ray forgot other people could read, had a right to read a fucking book when they felt like it.

Ray just needs to get out of the house for a little while, Tony thinks.

Ray just needs some fresh air. Have a beer, smoke some weed, take a walk around the neighborhood and relax. Tony has it all laid out in his mind, the speech he’s going to give Ray about how fucked up everything is, how Ray needs to get back up to school before it’s too late. Anybody who likes reading books as much as you do needs to be getting a college education, can’t be fucking up a chance like this. He’ll shake his head and tell Ray he understands wanting to be here for your mama and all, but sometimes you got to just put shit aside and go for yours because how you supposed to help anybody else if you can’t even help yourself? Sam would have wanted him to say all that. Would have said, Listen to Tony, you know Tony got plenty of sense, always has.

He’s going to tell Ray about how proud of him Sam always was. Tell him that as much as Sam rolled his eyes, everybody could see how much he liked saying it. Naw, that doofy herb ain’t here no more. He up at school. The eye-rolling was just reflex. My baby brother, up at college . . . He’ll make up a little lie about how one night he and Sam actually talked about it, tell Ray how ashamed Sam was for hitting him, especially that last time. Knocked his books on the floor, slapped Ray across the face. Now pick it up. And really there was something pitiful about it, big man like Sam hitting a little boy like Ray. Tony could see that even then.

But of course, Tony wasn’t the one getting slapped. Tony was the one standing on the sidelines watching, the one who had his hands out when it was over. The one who dusted him off, handed him back his book, said Here you go, Ray and Damn, that motherfucker is mean. And Ray cut his eyes and said, Oh, that son of a bitch is probably just high, he don’t even know what planet he’s on half the time, which Tony knew wasn’t true. But he let Ray say it because it made him stop crying and sometimes people just say things.

Tony spins around, opens the door to the pantry. Ray’s mama has got all kinds of shit in there: baked beans, Vienna sausages, Del Monte canned peaches, SPAM, a half-full jar of Folgers crystals that has probably been sitting there for years. Tony sucks his teeth, thinking how his grandma is the same way. Can’t throw anything out, no matter how nasty or old. Jars of flour, baking powder, baking soda, cornstarch, cornmeal, sugar. He can see how someone might get confused in a pantry like that. If they were crazy, say, or couldn’t smell nothing because their nose was too stuffed up from crying all the time.

Ray’s mother is not taking very good care of herself these days. That’s what Tony’s mother said when he told her he was going out to visit Ray: Saw her shuffling around the supermarket the other day, poor thing with her wig on all crooked and walking around in that nasty house-dress. Just grieving, poor thing. She not taking very good care of herself these days, looks like. If Tony’s mother hadn’t pointed it out to him, he might not have even noticed. To him, Ray’s mama just looks old. But she always looked like that, even when they were kids.

Tony stands there for a minute, looking up at a jar of what appears to be powdered sugar. He glances over his shoulder and decides that if Ray walks in and asks him what he’s doing he’ll just shrug and tell him he’s got a sweet tooth. He twists the top off the jar and opens a drawer near the sink, looking for something to put it in. He is pulling out a plastic Ziploc bag when he hears a knock on the front door.

He walks back into the living room and sees Raymond peeking out the front window.

“I told you, man,” Tony says. “It’s the changing of the guard.”

Raymond nods. “Just wait here. . . .”

7.

The girl watches Raymond walk out the front door and shut it behind him. She puts her glass of water on the table and stands by the window. She sees Raymond heading out to a car parked by the curb. An arm spills out of the driver’s-side window and it is a man’s arm, thick and muscular, fingers outstretched to clasp Raymond’s hand. Suddenly Raymond looks different to her: thin and awkward, like a boy.

“That’s his brother Sam’s friend, Sean.” Tony shakes his head and sits down on the couch. “Everybody’s cool now, but let’s see how long that lasts.”

Another man’s hand appears, dangling out of the rear window, holding out a forty-ounce bottle of beer.

“Somehow they got it in their stupid heads that Sam took something that belonged to them and hid it somewhere, maybe right here in his mama’s house.”

The girl watches Raymond take the bottle, twist off the cap, and spill a sip onto the pavement before raising it to his lips.

“And you know what’s fucked up? I mean really fucked up? I’m starting to think that too.”

When the girl turns around, Tony is staring at her from the couch. He lowers his eyes, looks down at the book.

“Hey. You really read this? For real?”

The girl nods. “Aunt Ruby gave it to me.”

“Well, who the hell is Aunt Ruby?”

“Mama’s friend. She came down with us to Grenada, as part of the Creative Unity Brigade.”

Tony picks up the book. Somehow this makes sense to him. Of course there is a Creative Unity Brigade. Somewhere. Full of the righteous, marching proudly, two by two, with their fists in the air. The book is a call to action; he can tell that just by looking at the cover.

“That why y’all moved down there, to that island? Help the needy, feed the poor? That kind of shit? What, you part of a church group or something?”

“Not really.”

He flips the book over and stares at the back cover. Outside he can hear the revving of a motor, music blaring through the car’s open windows, the screech of brakes as it pulls away from the curb.

“Why did you stop?” he asks the girl. “I mean, why did you all come back?”

The girl stares at him. She has to think for a moment about how to answer because in truth, no one ever asks her that. They ask why she went but never why she came back. Most people she has met here don’t even know where Grenada is, except when they sometimes say, Didn’t we already bomb the shit out of that place years ago? And everyone who hears about the Brigade seems to assume that it was bound to fail simply because it did.

“Aunt Ruby. She gone now.”

“Gone where?”

“In the kitchen. She take a bottle of pills.”

Tony turns away from her. Tries to picture the woman, Aunt Ruby, but can’t. So instead he thinks about Sam, someone he had known all his life, someone he loved, truly. He rises to his feet and as he walks across the room he thrusts an abrupt finger towards the cardboard box. “You see all them books? The one who left them for Ray? He gone too.”

He peeks out the front window. He can see Ray still standing on the sidewalk, staring down the block. He has already figured out that Ray is different, that something is not quite right. Him and his mother both stuck in the righteous purging of grief. One had history, the other had Kool-Aid, and from where Tony stood he couldn’t see how either was doing them a bit of good.

He looks at the girl.

“Hey, girl. Look what I found.”

Tony reaches into his pocket and pulls out the plastic bag full of white powder. He opens it up and pokes it with his finger.

“You know what this is?”

One had history, the other had Kool-Aid, and from where Tony stood he couldn’t see how either was doing them a bit of good.

The girl stares down at it, then up at him. If she had to guess, she’d say sugar.

“It’s medicinal is what it is,” Tony says. “Like what the doctor give you when you got a cavity. Like Novocain. Rub it on your gums and the next thing you know, you can’t feel a thing.” He stands beside her and holds the bag open. “Go ahead and try it.”

The girl stares back at him while he nods. She dips her finger inside the bag and rubs the powder onto her teeth.

“You see what I mean?”

A dry, metallic taste stretches up from her tongue, shoots through her nostrils, and clears a space for itself in the front of her brain.

“You see what I mean?”

All of a sudden she’s dizzy. She sits down in the La-Z-Boy, struggling to keep her eyes open. Tony stands there, studying her face. After a moment he backs away from her slowly and sits down on the couch.

“I like you, girl. For real.” He nods. “You just keep your head up. You’ll be all right. You know why? Because you’re cool. I could tell just as soon as I saw you, standing out on that porch.”

He winks.

“That’s why I want you to listen to me, okay? I’m gonna tell you a secret. And don’t tell Ray I told you either. Because I love Ray’s mama and all . . . she’s like an auntie to me. But she also silly simple. You know what I mean?” He twirls his finger in the air near the side of his head. “Something not quite right. And if I were you I wouldn’t drink any more of that woman’s nasty Kool-Aid. You understand? Because I wouldn’t . . .”

Tony shakes his head.

“Not even if you paid me.”

8.

Raymond stands next to the curb, watching his mother’s car pull into the driveway. When she opens the door and the light clicks on he can see the frantic look in her eyes, lips moving as she mutters to herself. She can’t help him, he knows that. It’s all she can do to keep herself upright, drag herself out of bed in the middle of the afternoon, open the door for her little flip babies, collect her parcel of dimes.

He helps his mother unload her grocery bags from the car and listens to her talk to herself. Blaming herself, trying to make sense of what happened. How could she have lost her son? How could things have possibly gone so wrong? What could she have done differently if only she had tried? She looks at Raymond, a quiet hysteria animating all her gestures: “Help me get these bags in the house. I’ve got work to do, I’m running out of time.”

That is what is needed more than anything, he thinks. Time. So much history to sort through, struggling to make room for itself, scribbled in the margins of every page. The books he found in the back of his brother’s closet are full of secrets, the private truths of a man talking to himself, whispering things that Raymond could scarcely imagine his brother saying out loud. Clearly Sam was standing on the precipice of a new understanding when he passed, and now there is no one to finish his thoughts but Raymond. He doesn’t want to be interrupted. Not yet. He still needs time.

“Is that Tony sitting in my living room? Go tell that fool boy to come out here and help me with these bags— ”

When Raymond walks back inside the house he takes one look at the girl sitting with her mouth hanging open and Tony shoving a plastic bag into the pocket of his jacket and knows that something is very wrong.

“What the fuck did you do?” he says, and Tony laughs. Tony laughs, even as Raymond pulls him up by the collar, pushes, and then hurls him towards the front door. Even in the midst of grief, Tony is still laughing.

“Remember what I told you, little girl. . . .”

A door slams. The girl can hear them scuffling out on the porch. She leans back in the La-Z-Boy and stares up at the ceiling, trying to negotiate the shifting rhythms of her own heartbeat. She is in the present, she is in a suburb of the south, and everything is quieter than before. There is no fist in the air, no promise of the Creative Unity Brigade. When she looks up she does not see the words from a book or her mother’s hands or Aunt Ruby’s face or the kids in the yard or the Rastafarians in a clinic waiting room. She doesn’t see a needle or blue lights or even the little brick house across the street from Henry’s Bar, where her uncle lives. When she looks up at the ceiling, she sees something even better.

A blank page.

And just as she is about to smile Raymond appears, hovering above the chair. She stares up at his pursed lips, dark eyes, eyebrow arched. He reaches around, takes her by the arm, and gently pulls her to her feet.

“Little girl? It’s time for you to go home.”

9.

The Flip Lady stands in her bright yellow kitchen, unpacking a bag of groceries. She takes out a large pot, fills it up with water from the sink, and sets it on the counter. She empties a canister of Kool-Aid and stirs. She adds a cup of sugar, watching the powder swirl through the purple liquid then disappear as it settles on the bottom. She thinks for a moment, then scoops out another cup.

“Little heathens.” She chuckles. Just like Tony, always thinking she can’t see past their smiles. But she watches everything from the kitchen window and she has seen it all. Nothing has changed. It’s just like before: she always could tell the good from the bad.

“Bet y’all sleep good tonight,” she mutters to herself. She doesn’t do it for the money. No one has to thank her.

She smiles, thinks about all the little flip babies in this world. It doesn’t last, nothing does. But for now they still come running, gather around her back porch, hold their hands out for the promise of something sweet.

And she gives it to them.