What even is time? I had a couple conversations this past year, some of them surrounding the publication of my non chronologically-structured novel We Do What We Do in the Dark, during which the concept of “queer time” came up, this idea that LGBTQ people experience time differently, almost four-dimensionally like Vonnegut aliens. We constantly look back to see evidence of our nascent selves, when queerness was less an identity than it was a feeling, and we constantly look forward to imagine a world finally ready to welcome us with open arms.

It’s hard to see the past clearly—so many of our childhoods are marked by denial instead of discovery—and even harder to see the future, especially for those of us who came of age in the shadow of AIDS and now find ourselves still very much in the throes of a pandemic that has disproportionately affected the most marginalized. Add to that the banning of our books, the rolling back of our civil rights, the daily threat of hate-fueled violence.

As Alex Marzano-Lesnevich writes in their brilliant essay on gender and futurity: the future is “The very thing we are all trying to hold onto, as we wait for it to arrive.” How difficult it is to imagine “the projected shape that future makes. The shadow (or light?) it casts over the present.”

Shadow and light, past and present and whatever comes next. These are the reconciliations that inform our stories. This is what art does. It allows us to see, concurrently, the past and the present and the future. It allows us to see, concurrently, the light and the dark. This is what queer art specifically does: it shows us that we have always been here and we always will be. Queer stories, like the ones listed below, do more than shine light on the shadows. They are the light in the shadows. They are living documents of our lives.

The New Life by Tom Crewe (Jan. 3)

Crewe, an editor at the London Review of Books, debuts with a stimulating, sensuous novel set in 1890s Britain and centered on two men, each in their own complex hetero-passing marriages who collaborate—through Zoom letters—on a chronicle of queer life that will challenge Victorian sexual mores.

Decent People by De’Shawn Charles Winslow (Jan. 17)

Winslow’s incredible debut, In West Mills, a largehearted decades-spanning tale about the insularity and kinship of a close-knit community, was awarded The Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize. In this follow-up, Winslow returns to West Mills with a story exploring the reverberations of a shocking murder.

I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself by Marisa Crane (Jan. 17)

In the dark mirror of this inventive dystopia, we see an America in which a shame-obsessed carceral system attaches shadows to those they’ve deemed wrongdoers–chimerical reminders of their crimes that sometimes linger into the next generation. Crane’s story centers on a new mother, grieving the loss of her wife, whose daughter has been born with two shadows. What unfolds is a tale of a uniquely queer form of parenthood and resistance.

Tell Me I’m Worthless by Alison Rumfitt (Jan. 17)

Mike Flanagan, eat your heart out: Rumfitt’s fantastic first novel queers contemporary haunted house horror with this ghastly tale of two friends who, in attempt to put spectres of the past and present to rest, return to the abandoned house in which they spent one terrifying, traumatic night.

After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz (Jan. 24)

A la Michael Cunningham’s The Hours, Lambda finalist Schwartz’s first novel forms a triptych of women who refuse to be stifled by societal expectations of femininity. The story unfolds as a series of sensuous fragments that would make the titular Greek poet proud.

Big Swiss by Jen Beagin (Feb. 7)

With Pretend I’m Dead and Vacuum in the Dark, Whiting Award-winner Jen Beagin swept onto the scene as a singularly sardonic sad-girl absurdist. Those two novels were about a housecleaner in New Mexico who takes suggestive photos in her clients’ abodes; for Big Swiss, Beagin brings her acerbic wit to the Hudson Valley. The story centers on Greta, a transcriptionist for a sex therapist dwelling in a dilapidated Dutch farmhouse who soon becomes obsessed with one of her employer’s newest clients (the titular Swiss, a European gynecologist who’s never had an orgasm). This is erotic cottagecore as only Jen Beagin can do it.

Confidence by Rafael Frumkin (Feb. 7)

Theranos but make it gay. In this Ripley-esque romp, two men—occasional lovers—create a fake empire based entirely on their own charisma and an impossibly auspicious wellness product that promises bliss to those who use it.

Couplets by Maggie Millner (Feb. 7)

Millner’s story-in-verse—trying to classify this wonderfully amorphous book about the fluidity of desire is entirely beside the point—centers on a woman who falls in love with another woman for the first time, a relationship that upends her ideas of intimacy and herself: “That lust to me was wanting to transgress/beside another. To be so totally compelled./To share a truth you have to lie to tell.”

Endpapers by Jennifer Savran Kelly (Feb. 7)

In Kelly’s first novel, a New York bookbinder coming to terms with her genderqueer identity finds a love letter scribbled on a page torn from a midcentury lesbian pulp novel. What ensues is a dizzying, intimate mystery, an exploration of how we become engrossed in the stories of others in order to tell ones of ourselves.

Hijab Butch Blues by Lamya H (Feb. 7)

One of the most difficult and painful experiences of growing up religious and queer is figuring out whether you can reconcile those two important facets of your life. Often, that reconciliation feels impossible. Yet Lamya H’s memoir about coming of age as a queer hijabi Muslim offers an inspiriting vision of a world in which queerness and the Quran are not only compatible but illuminative of one another.

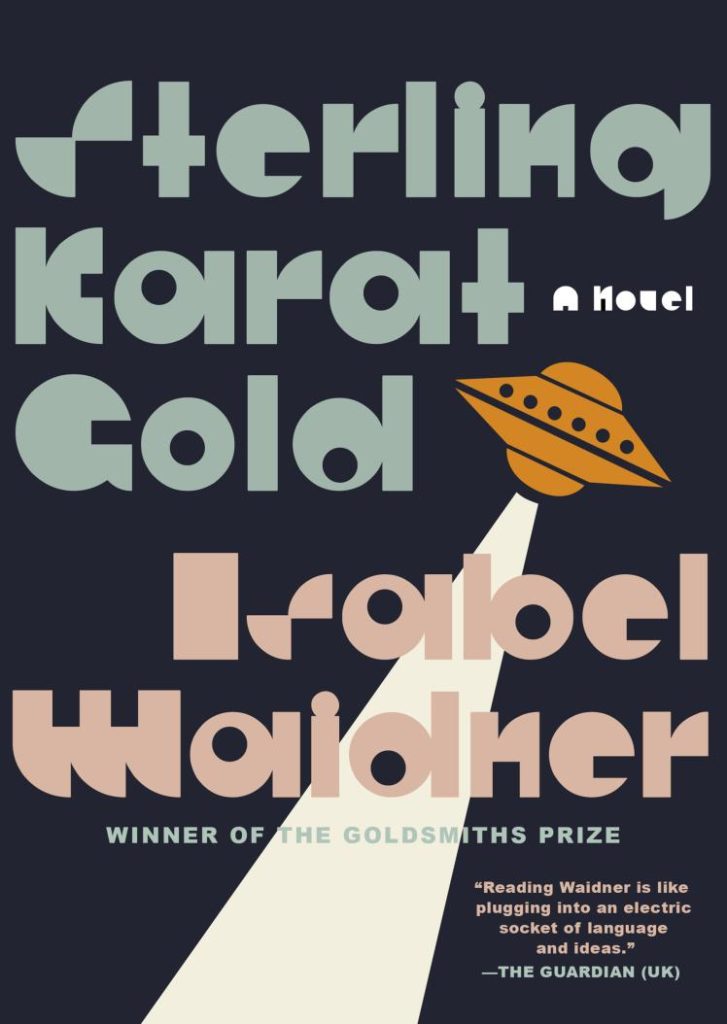

Sterling Karat Gold by Isabel Waidner (Feb. 7)

In a recent New York Times feature on how to read one’s way through London, Booker-winning author Bernadine Evaristo lavished this praise upon Isabel Waidner: “Their explosive sensibility and style are as far removed from mediocre prose and middle-class manners as you can imagine.” And it’s true: Waidner’s refreshingly absurdist third novel, which won Britain’s Goldsmiths Prize, is a topsy-turvy journey across Camden Town from the point of view of a nonbinary migrant, a Kafkaesque adventure that encompasses bullfighters, footballers, time-traveling spaceships, and a high-drama trial.

Sweetlust by Asja Bakić (Feb. 14)

A teen table-tennis prodigy attends a summer camp and discovers something sinister stalking the girls there. A trans woman living in an America sans men joins her friends on an excursion to an erotic VR theme park. Bakić second collection, following Mars, offers spectral, speculative tales of womanhood’s fluidity and ferality.

Wanting: Women Writing About Desire, edited by Margot Kahn and Kelly McMasters (Feb. 14)

Melissa Febos on the musicality of orgasm. Kristen Arnett on the wild tenderness and tender wildness of yard work. Keyannah B. Nurse on polyamory as a powerful archive of history and pleasure. Torrey Peters on the fried tilapia that portended the end of her marriage. The essays in this voluptuous, multivarious volume comprise an essential compendium of female desire.

Scorched Grace by Margot Douaihy (Feb. 23)

The inaugural release of Gillian Flynn Books, Scorched Grace centers on Sister Holiday, a chain-smoking Catholic school music teacher turned amateur sleuth. If you’re not sold by a punk rock nun solving mysteries then can your soul even be saved?

Finding the Fool by Meg Jones Wall (Mar. 1)

Autostraddle columnist Meg Jones Wall offers an all-levels guide to reading the tarot, a compendium of resources to help beginners and longtime practitioners alike conjure from the cards a deeper understanding of one’s inner and outer worlds.

Monstrilio by Gerardo Sámano Córdova (Mar. 7)

The beastliness of grief is heartbreakingly rendered in Córdova’s folklore-inflected first novel, which follows a bereaved mother taking the lung of her recently deceased son and nurturing it back into the boy she lost. But death can never be totally thwarted, and the son that returns isn’t quite the same.

Brother and Sister Enter the Forest by Richard Mirabella (Mar. 14)

Mirabella’s debut novel—about a pair of once-close siblings and how the bruises of their youth swell into adulthood—is both bracing and a balm, his softly disarming sentences like cotton puffs that absorb the pain of deep cuts.

The Dance Tree by Kiran Hargrave (Mar. 14)

In sixteenth century France, a woman began to dance in the Strasbourg city square. What started as an individual’s mysterious paroxysm became a full-blown plague of supposedly religious mania. Hargrave, whose previous novel The Mercies was a bewitching work of historical fiction, sets her tale of three women trying to break free of society’s bonds against the backdrop of this strange phenomenon.

The Lost Americans by Christopher Bollen (Mar. 14)

Bollen is a modern master of the Highsmithian literary thriller. His previous book, A Beautiful Crime, was a Venice-set caper about lovers turned con men, a mystery that tapped into the Floating City’s labyrinthine nature. Here, he flies readers to Cairo to uncover a mystery about an American defense contractor who’d reportedly died by suicide and his increasingly suspicious sister working to understand what really happened.

Biography of X by Catherine Lacey (Mar. 21)

Over the course of three novels and a story collection, Catherine Lacey has become one of our most innovative literary practitioners, a writer capable of bending gender and genre. Lacey’s fifth work of fiction is a widow’s chronicle of her late wife, an artist known as X who has remained an enigma to the world at large and perhaps most of all to the woman who loved her.

The Fake by Zoe Whittall (Mar. 21)

Stories about scammers permeate contemporary media partly because, for the outside observer, there’s a sense of superiority at being able to preemptively spot the red flags, to declare “This would never happen to me.” But the head and the heart are seldom in sync, especially for the lonely and vulnerable. Take recent widow Shelby and divorcé Gibson, two people who, unbeknownst to one another, have fallen for the same woman, Cammie, a swindler who might just be the match to the tinder of their lives.

The Heavy Bright by Cathy Malkasian (Mar. 28)

Chronicles of Narnia meets The Handmaid’s Tale in this gorgeous allegorical epic. It’s set in a fantasy world in which men known as Commanders ravage and pillage the land and its people, their power coming from ancient black stones passed down to them by their ancestors. The destruction goes unchecked until one day, a young tomboyish girl discovers the secret to defeating the Commanders once and for all (and falls in love along the way).

Small Joys by Elvin James Mensah (Apr. 11)

A largehearted look at the importance of found family, Mensah’s first novel focuses on the lifesaving friendship between a cast-off son on the brink of self-harm and the easygoing new roommate whose affection becomes a balm. Small Joys dwells in the sometimes-fleeting moments of pleasure and happiness that stave off the iniquities of the world.

Juno Loves Legs by Karl Geary (Apr. 18)

Shuggie Bain vibes abound in this tenderhearted tale by Karl Geary, whose previous book was shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award and France’s prestigious Prix Femina. It follows two misfit teens in 1980s Ireland whose love for one another offers solace from the sociopolitical strife of an Emerald Isle in the midst of growing pains.

The Weeds by Katy Simpson Smith (Apr. 18)

The Everlasting, Smith’s previous novel, was a polyphonic, multi-century-spanning trip across Rome, and here she returns to the Eternal City for a story about two women hundreds of years apart who are nonetheless connected by the solace of botany, two lost souls cataloging plants in the Colosseum ruins in an attempt to mend their own broken hearts.

The Skin and Its Girl by Sarah Cypher (Apr. 25)

Cypher’s vibrant debut centers on Betty, a Palestinian-American girl born with cobalt blue skin. In her adulthood, she discovers and tries to decipher journals kept by her aunt—the family matriarch and keeper of their lore—a complex woman whose story begins to color in pieces of Betty’s own.

If Tomorrow Doesn’t Come by Jen St Jude (May 9)

How can we make room for love–love of another, love of self–in the midst of perpetual apocalypse? It’s a question many of us have been asking on the daily these past few years, and it’s a question Jen St. Jude posits in her full-hearted speculative debut. Avery is a college student whose feelings of loneliness and hopelessness are upended when the world learns an asteroid will destroy life on earth in exactly nine days. St. Jude is a gorgeous writer (and vital literary citizen!) and her depiction of finding light in the ever-present dark will resonate in our precarious present and throughout whatever tomorrows we have left.

The Celebrants by Steven Rowley (May 16)

Every year for the past three decades, a group of friends who met in college congregate at a house in Big Sur to hold faux-funerals for one another, celebrating and/or mourning life events and letting one another know how much they are loved while they’re all still alive–leave nothing left unsaid, is the unofficial motto. But this year is different: one of them, Jordan (whose husband is also named Jordan and so they are therefore ‘the Jordans’) has terminal cancer. Thing is, he’s not telling the rest of them. Rowley’s novels deftly oscillate between tear-jerker and knee-slapper, books that brim with all of life’s big and small emotions, and his latest is no exception. It might just be his best yet.

Dykette by Jenny Fran Davis (May 16)

The Big Chill goes gay in Davis’s raunch-com about six queer Brooklynites spending the holidays at a Hudson farmhouse. Come for the sometimes-riotous relationship drama, stay for the myriad cultural in-jokes (Lea Delaria, Maggie Nelson, and Jordy Rosenberg’s Confessions of the Fox all get shoutouts).

The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor (May 23)

Taylor probably needs no introduction to readers of these pages, but here goes: with his Booker-nominated novel Real Life and his Story Prize-winning collection Filthy Animals, Taylor has proven himself an exacting portraitist of the inner lives of outsiders, of intimacy’s grandness. He returns with a polyphonic novel centered on a group of young Iowa City friends on the cusp of whatever comes next and how their relationships help and hamper them along the way.

Lesbian Love Story by Amelia Possanza (May 30)

In her work as a publicist, Possanza has championed many wonderful writers, and now we get to champion her and her incredible book, a work of history and memoir that crystalizes what so many queer women know: it’s impossible to write our own autobiographies without the biographies of those who came before us. Subtitled “A Memoir in Archives,” Possanza’s centuries-spanning document–which melds her own story with hidden, intimate histories of drag kings and olympians, artists and activists–is a manifesto of love: of erotic love and platonic love, of familial and communal love, and maybe most importantly, self-love.

The Male Gazed by Manuel Betancourt (May 30)

Do I want them or do I want to be them? This is perhaps one of the most central existential questions queer people ask themselves on the daily. Betancourt, one of the best film/television critics around, probes this quintessential conundrum by examining what he has learned about masculinity through watching movies.