I have long been fascinated by books about the early years of the AIDS crisis.

Paul Monette’s Borrowed Time: An AIDS Memoir from 1988 remains a cherished work; last year’s Let the Record Show by Sarah Schulman and It Was Vulgar and It Was Beautiful by Jack Lowery provided crucial insights into the world-changing work of ACT UP; this year’s Love Your Asian Body by Eric C. Wat showed how the Asian American community in Los Angeles mobilized against AIDS.

But for as plentiful as these books are, the vast majority live in the world of nonfiction—Rebecca Makkai’s excellent The Great Believers from 2018 is a recent fiction example, notably set not in New York City, but in Chicago. Before that, prominent titles include the later books in Armistead Maupin’s Tales of The City series published in the mid-and-late- ‘80s and Rat Bohemia, also by Sarah Schulman, in 1995.

Fiction is just as important to understanding our history as nonfiction, but it’s the latter that continually takes up the most space, both figuratively and literally, on our bookshelves.

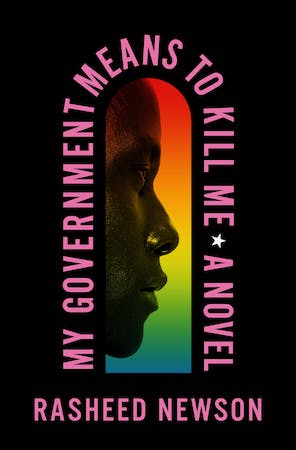

With his crackling debut, My Government Means to Kill Me, Rasheed Newson seeks to change that by offering the queer canon a new hero, one we’ve seen countless times yet rarely at the heart of the story. Trey is Black and queer, effeminate and fearless, unafraid of acting rash when it’s for the good of his community. He’s a character who could easily grow up to be Belize from Angels in America. Reading the book, I felt like I was getting a secret glimpse of how Belize’s last few years as a teenager might have gone before life in the city turned him into a hardened queen. The novel is a sexy, necessary, relentless call-to-action, not to mention an expertly paced read. I got to speak to Newson about his refreshing use of gay sex scenes, fictionalizing the private lives of real historical figures, and why he can’t believe, “something this unapologetically Black and this unapologetically gay is attracting the attention and the positive reception that it has.”

Jeffrey Masters: The novel is written in first person, but from the perspective of someone looking back on their life, as if it’s a memoir. What made you want to tell the story in that way?

Rasheed Newson: Well, I wanted all the newness and excitement of being 17-to-19-years-old. But without the benefit of time and reflection, there would’ve been a lack of maturity in it, right? I wanted it both ways. I wanted a young protagonist who was able to then look at himself with the benefit of age.

JM: It was a profoundly different experience to be Black and gay in the 1980s compared to today. What kind of work or research did you do to get into that mindset for the character?

RN: To really get into that time period, what was good was just reading history, reading ACT UP minutes, and talking to people about what that experience was like.

You send them a white man that they imagine could be at their dinner… because you’re trying to appeal to the power structure.

The first footnote in the book is from Sylvester who died of AIDS and laments that it’s still considered a disease for gay white men. That exclusion is on the lips of everybody from the era and that’s what was happening, politically speaking. The gay rights movement wanted to try to get sympathy from congress. You’re dealing with a bunch of white men and so you send down someone who reminds them of their son. You send them a white man that they imagine could be at their dinner. And you’re doing this because you’re trying to appeal to the power structure. It does, however, silence all those other voices. All the other people suffer.

JM: That’s also reflected in the first major piece of legislation passed to help those living with AIDS, the Ryan White CARE Act. It was named after a nice, young, white, straight boy.

RN: …who got it through no fault of his own. It was a blood transfusion. There was no blame that could be attached to him the way. It was attached to other people who were dying from the disease.

JM: This is the first book I’ve read where Bayard Rustin, a legendary figure in the civil rights movement, pops up half-naked in a bathhouse. His sexuality has been erased in many ways and you gave that back to him.

RN: I wanted to remind everybody. You know he was a gay black man, but you probably never thought about his sexual needs. What were his tastes? What were his appetites? Where did he go to get off? Those aren’t insignificant parts of a person.

I thought it made him more approachable for Trey. In a normal setting, if they met at a cocktail party, Trey probably wouldn’t have had the nerve to go up and start a conversation with him. But there’s something being leveled about the fact that they were in a bathhouse. Like, we’re all here in our towels. We’re all checking out the trade. It humanized him in a way that I think made that relationship possible.

Also, I did feel a little bit of safety—and I don’t think it’s something that besmirches Mr. Rustin’s reputation—but he was arrested in the ‘50s in Pasadena for solicitation. He was in a car and got picked up by the cops. And so, I was like, “Oh, that’s right. He went cruising.” He went cruising and he did it at a time when our sexuality was being criminalized, so he got arrested. That, I think, is the thing that woke me up to the fact of, Yeah, he’s a man. And you know what men like to do? They like to have sex.

JM: There used to be this idea that you can’t write too explicitly about gay sex if you want to sell a lot of books. Did you receive any pushback on the many sex scenes?

RN: No. And I was prepared to have to fight for them. My husband at one point was reading an early draft and he said, “Do you think they’ll let you keep the rimming?” I adore him. I was like, “I love that we’re having this conversation.” And I said, “Well, I’m going to try.”

Nadxieli Nieto at Flatiron is my editor and it never came up. Never once was she like, “You need to pull this.”

JM: You also wrote it so that you can’t delete the sex and still have the book work.

Our sex lives are important to us. They are part of our identity [and] how we relate to the world.

RN: Yeah. I mean, one of the things I’m trying to suggest is that sex is not frivolous. This is not some trashy, tawdry detail. Our sex lives are important to us. They are part of our identity. They’re part of how we relate to the world. They’re part of how we connect to other people and they tell you a lot about a person. And so I don’t think it’s trivial at all to examine the sex life of someone.

JM: All of the sex also helped to keep the book from focusing on trauma, only.

RN: No matter how dark it is in history, people find a way to have joy. They find a way to have a release. They have sex. It’s a part of human history. I just wanted to be honest about it and I wanted to present it in a way that didn’t try to make some sort of moral judgment about it.

JM: One thing you capture is this feeling of whiplash that queer people can experience around how their queerness is treated. For example, Trey’s femininity is a negative thing growing up. He’s called a sissy and made fun of. Then he moves to New York City and suddenly these same qualities are what make him desirable to other men.

RN: I think a lot of us who are queer and move to a bigger city experience that what would have gotten you beaten up in your hometown now has everybody at the bar trying to get at you. And it’s sort of heady and it’s sort of dizzy.

I’d also point out that that feeling of “This is something that’s sort of held me back or held against me it suddenly is celebrated” captures a lot of what I feel about how this book is being received. I can’t believe something this unapologetically Black and this unapologetically gay is attracting the attention and the positive reception that it has. My plan when we published this was that it would be a book that we’d sell in gay bookstores. I didn’t think it was going be in Barnes and Nobles. I thought there was an audience for this, but I can’t believe it got written about in The New York times.

And part of that is like, “Oh, you like this now?” Something has shifted. I don’t want to be a Pollyanna. It hasn’t all been for the best, but something has shifted where I think this book is able to have a much wider place now than it could five or 10 years ago.

JM: Given those expectations, it doesn’t seem like you changed elements to make it more commercial or “palatable” to non-queer audiences. There are multiple trips to the bathhouse, one of the main characters is a sex worker.

It’s about a queer, femme, Black guy during the height of the AIDS crisis in New York City.

RN: I would love to say I did that out of some kind of courageous, self-righteous stand. I didn’t think there would be any hope in taking those things down. It’s about a queer, femme, Black guy during the height of the AIDS crisis in New York City. I didn’t think there was anything to gain by trying to tone it down. I just said, “Well, you might as well go ahead and just write this the way you think it’s supposed to be written. People who aren’t going to like it, aren’t going to like it anyway. You’re not winning them over.” I couldn’t suddenly walk into a very conservative place and say, “Look, it’s a femme gay hero, but don’t worry, he doesn’t take his pants off.” They still aren’t reading that book.

JM: It seemed to avoid neat storytelling across the board. There’s no happy romantic ending for Trey or grand reconciliation with his family.

RN: There’s also literally no love story, which is something I didn’t even know. A friend of mine pointed that out. There’s sort of this trope that whatever is ailing Trey will be healed when he finds a boyfriend or when he finds someone who loves him just as he is. I don’t know that you get that at 19.

JM: I didn’t register that because, to me, the love story was between Trey and his best friend, Gregory. The love story was their friendship.

RN: At the beginning, when some people read it, they felt like they were waiting for Trey and Gregory to fall into bed together. It led me to tell the audience very early on that these two are not going to get together. Like, it’s never going to happen. Otherwise, the audience wasn’t paying attention to all this other stuff going on. They were almost going into every scene saying, “Oh, is this where it’s going to finally happen?” It’s what your brain does. You’ve been trained to anticipate that.

JM: Trey eventually enters the world of AIDS activism. Did you debate about whether he should contract HIV in the story?

I wanted to live in that space that I feel a lot of people who lived through that time and didn’t contract HIV talk about, which is the sheer randomness of it.

RN: I thought about it, but it would throw the weight of the story off. Suddenly, we’d be dealing with that and I wanted to live in that space that I feel a lot of people who lived through that time and didn’t contract HIV talk about, which is the sheer randomness of it. When they look back on their lives, they don’t understand why someone else they know got it and they didn’t. I liked that space and it felt a little less familiar than what I’ve seen when it comes to other HIV stories.

JM: The book only spans two years. He very well could discover that he’s living with HIV in the years that take place after the book ends.

RN: Yeah, as I explore taking this book to the screen and ask, “Do you do this as a TV show? Or you do this as a movie?” One of my hesitations has been that I thought, “Well, if you do this as a television show, you’re going to blow past the book in the first season. And by season three or four, there’s going to be this drumbeat of “Why doesn’t Trey…why isn’t he HIV-positive?” And, “Are you just doing this because you love the character so much and you don’t want to go through the door?”

JM: Have you found a solution to that?

RN: I don’t know…one of the things that’s interesting about television is that you never know how fast a show is going to move until you are on the show. Like, is this a show that covers years, or is this a show that covers days? And so there is a world where not that much time passes and maybe you don’t have to get very far beyond the calendar in the book. And so then you wouldn’t have to face it.

JM: You’ve spent your career making TV. Why decide to tell his story in a book and not TV?

RN: I didn’t think there would be much of a reception or an appetite for it on TV. Now that it’s IP, that changes the equation. But I thought if I walked in with this as a pilot script, automatically there are only a handful of places I could even think of taking it.

Television is a big tent business. We want as many people to watch and the one example I thought of was Pose, which was incredible. And I think there’s probably a lot of people who would’ve said, “We’ve already covered this territory.” And then Generation came out and had a Black queer lead and it only lasted one season. I wanted this story to be told in the boldest colors without any compromise and television is collaborative by nature. We make compromises in television. That just is how it goes.

Here’s what’s great about television. There are a number of times in television where we’ve been stuck creatively, artistically. And luckily someone else has the answer to a problem and we get to move forward. Writing a book, you have to come up with all the answers.

JM: The origin story of ACT UP as I’ve always heard it has Larry Kramer making a fiery speech at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center in New York City. This inspired people to meet and then form ACT UP. In the book, you pose a slightly different story.

RN: I poke at it because…and the thing I made up, I absolutely made up. That’s how I was taught that ACT UP started, that Larry Kramer gave that speech, but when you look at a lot of the original leaders in ACT UP, they weren’t at the speech that night. They weren’t there. And other people had proposed a similar organization with a similar structure for years. So, it was already floating out there.

The people who would pull it together weren’t at this moment that was supposed to inspire the masses, but that’s what storytelling is and that’s what history becomes. It’s this feeling like Larry Kramer gave this incredible speech and ACT UP was born. That everybody went straight from there and hit the streets. And no, no, that’s not exactly everything. In political movements ideas have been flowing around, sometimes for generations before somebody can pluck it out of the air and make it a reality for a little while. But we like a neat story and so it’s just easier to tell those stories that way.

JM: In researching the book, what did you learn or discover that surprised you the most?

RN: I should have known this, but when we talk about HIV/AIDS in this country and we put a timeline together, we normally start with The New York Times writing their first story in 1981. And the fact is that there were hundreds, if not thousands of people in this country dying of AIDS in the ‘70s is something that just sort of escapes our attention and escapes our notice.

JM: That was one of my many takeaways from Sarah Schulman’s history of ACT UP, Let The Record Show. She wrote that HIV can be traced back to the 1940s in New York City’s homeless population. It was so common that they even had a vocabulary for how it transformed the body. They called it Junkie Pneumonia and The Dwindles.

RN: It had been happening for a long time and it shakes us out of our timeline. We like to think the war began on this date. The great depression began on this date. But these things have been rippling and they’re messy and they’re growing and growing and growing. Sarah Schulman’s book is great because it’s reminding you that typically when we pick a date, we’re choosing when did this become of note to the general population? There have been minority groups probably dealing with it for a very long time, suffering for a very long time. The date is just when the masses noticed.