Space exploration is widely seen as exciting and inspirational. It captures the public imagination in ways that other scientific endeavours do not, to the extent that kids dream of becoming astronauts and rocket scientists when they grow up. They do not, by and large, dream of becoming condensed matter physicists or materials engineers, worthy and interesting though those fields are.

Yet when it comes to recruiting people into the space industry, it seems the “cool factor” of space is not enough. According to Joseph Dudley, who leads a UK-based think tank called the Space Skills Alliance, around 50% of the UK’s 1300 space companies are struggling to fill vacancies. How can this be if space is so popular?

Dudley was speaking during a “skills session” at this year’s Appleton Space Conference, which is organized by RAL Space and took place on 1 December. Based on my previous experience of such sessions, I fully expected Dudley to cite the UK’s supposed shortage of STEM graduates as a prime cause of the sector’s recruitment struggles, and perhaps to complain about how terrible it is that Kids These Days™ want to be TikTok influencers rather than physicists.

It didn’t happen.

A losing game

Instead, Dudley summed up the space sector’s skills shortage in a single word: tech. “The core skills we are looking for are the same as everyone else,” he told conference attendees gathered online and in person at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory near Harwell, Oxfordshire. “We are competing with the tech sector, we are competing with Silicon Valley, and we are losing.”

Part of the problem, Dudley argued, is that the wider tech sector has responded to shortages by setting up flexible online coding “boot camps” for new trainees and career-changers. The space industry, meanwhile, generally expects applicants to have four-year degrees (or beyond) in physics, engineering or related subjects. This means that anyone who didn’t choose science subjects as a 14-year-old schoolchild is out of luck. “Where is our 16-week boot camp for Earth observation, for satellite ops?” Dudley asked rhetorically.

Another difficulty is that the roles most closely associated with space’s “cool factor” – astronaut and rocket scientist – are uncommon and seldom open to UK applicants. After flashing up a slide showing children’s clothing from UK stores branded with NASA’s iconic “meatball” logo, Dudley quipped, “Good luck finding the same for the European Space Agency or the UK Space Agency.”

Best and brightest

A further source of the space sector’s recruitment problems, Dudley suggested, is that many young people (especially young women and others from under-represented backgrounds) are convinced they’re not clever enough to do space science. For them, job adverts that scream, “Come work with the best and brightest people in the world!” are a deterrent, not a draw.

Finally, Dudley argued that the rise of the “new space” industry – dominated as it is by billionaire-run firms like Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin – has taken some of the shine off the industry’s image. “Our sector is being associated with environmental damage and space tourism for the rich,” Dudley warned. “We have to take swift action to make sure the brand of the space sector does not become toxified.”

Solving problems

Another speaker in the skills session, Anne-Marie Imafidon, reported seeing some of this “brand toxification” in action. As the co-founder of the Stemettes charity, which encourages girls, young women and non-binary folks aged 5-25 into STEM careers, Imafidon recently ran a workshop on science and sustainability. “The number of projects on space rubbish [from the students] was actually quite telling,” she observed. Among young people, she added, the attitude tends to be that going to space creates problems rather than solving them.

As for how to fix these issues, Dudley and Imafidon offered several proposals. These included alternative training programmes (boot camps, apprenticeships and the like); better recruitment practices and working conditions (40% of women in the space sector have experienced workplace harassment); more competitive pay; and raising awareness of other paths into the industry (including other space agencies besides NASA).

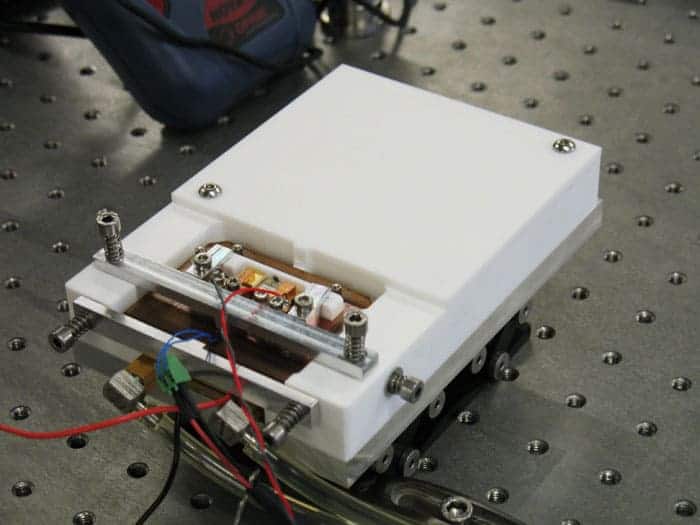

Earth-observation sensor adapted to hunt explosives

But alongside these practical steps, it seems the space industry could also do with re-thinking certain aspects of its image. Going into space, Imafidon said, is “not purely about following Elon [Musk] to the skies to create another population with all sorts of weird whims and ways”. It also helps solve problems down here on Earth. Moreover, X-Factor style competitions like the one for ESA’s latest astronaut class are wildly unrepresentative of the application process for, well, every other role in the industry.

If space firms can incorporate messages like these into their job adverts, perhaps they will find it easier to recruit people to help them reach for the stars.