The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is scheduled to launch on 24 December. To mark the event, Physics World is publishing a series of blog posts on the telescope’s technological innovations and scientific missions. This post is the fourth in the series. Read the first here.

Of the four instruments aboard the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), three – the Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec), the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and the Fine Guidance Sensor/Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (FGS/NIRISS) – operate at near-infrared wavelengths of 0.6 to 5 μm. For them, the telescope’s general, solar-shielded operating temperature of 36 K is cold enough. The fourth instrument, however, is designed to observe at longer wavelengths of 5 to 28 μm. For that, it needs even lower temperatures – 29 K colder than the other instruments, to be precise.

To keep the arsenic-doped silicon detectors on the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) at their operating temperature of 7 K, NASA has built the most sophisticated cryocooler ever launched into space. To call it a big refrigerator would be simultaneously accurate and a gross disservice to the innovations required to make it work.

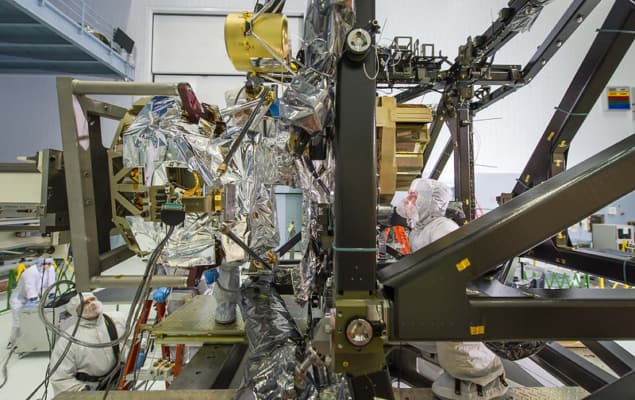

The cryocooler’s main section is its Cryocooler Compressor Assembly (CCA). Housed in the spacecraft bus, on the warm side of the telescope, it uses helium as a refrigerant, and is connected to MIRI (located about 10 metres away in the Integrated Science Instrument Module, behind the telescope’s primary mirror) by a labyrinth of tubes. Once the helium has been conductively chilled by a precooler inside the CCA, it gets pumped through these tubes to MIRI via the Cryocooler ColdHead Assembly (CHA). This device contains a valve less than a millimetre wide that acts as a “throttle” for the helium. As the helium expands on the other side of the valve, it drops to 6 K (one degree below MIRI’s operating temperature) thanks to the Joule-Thomson effect. It then passes behind MIRI’s detectors, picking up and exchanging their excess heat.

Space challenges

In a terrestrial cryocooler, such a system would be straightforward. In a cooler located on board a telescope in deep space, however, it creates certain challenges. An example is the distance between the pre-cooler and the helium-throttling valve. Normally, these two components are just centimetres apart, but on the JWST they are separated by many metres. Keeping the helium refrigerant cool on its journey though the telescope’s plumbing is therefore vital.

Another challenge is vibration. Any cryogenic system that contains moving parts will produce some vibrations, but aboard the JWST these vibrations need to be virtually non-existent, since any jitter from moving machinery could shake the optics and produce blurred images. Consequently, Webb’s cryocooler contains only two moving parts: a pair of horizontally opposed piston pumps in the CCA that are specially designed to operate with exceptional smoothness.

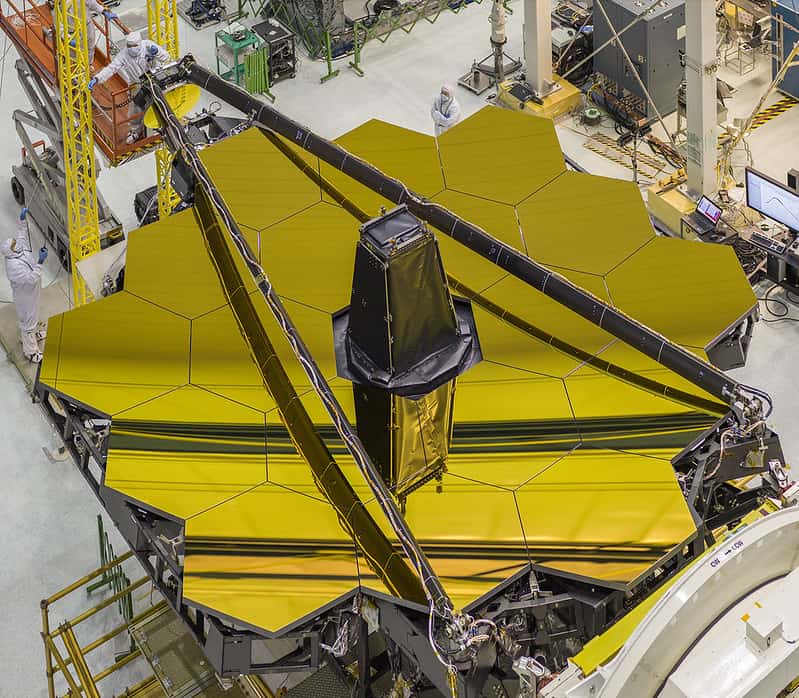

The ten-billion-dollar gamble: The JWST’s magnificent mirrors

One of the many unknowns surrounding the JWST is how long it can operate without astronauts to service it. Many factors – from a failure to deploy successfully to malfunctioning instruments that can’t be repaired because the telescope is out of reach of astronauts – could end its mission prematurely. However, unlike two of its predecessors, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope and ESA’s Herschel Space Observatory, it will not run out of coolant, because its cryocooler is a closed system. From a cooling perspective, then, the JWST should be fit to see out the decade, operating alongside other ground- and space-based instruments scheduled to come online in the mid and late 2020s.

Next: The JWST’s micro-scale windows on the universe