The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is scheduled to launch on 25 December. To mark the event, Physics World is publishing a series of blog posts on the telescope’s technological innovations and scientific missions. This post is the last in the series. Read the first here.

For most of the astronomy community, the long-delayed James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) cannot get off the ground soon enough. For exoplanet scientists, though, its repeated postponements brought a substantial silver lining. During the JWST’s lengthy sojourn in development hell, NASA’s Kepler and TESS spacecraft, among others, got on with the business of discovering new planets outside our solar system. As a result, when the JWST finally launches on 25 December, it will have an entire catalogue of promising new worlds to explore.

John Mather, the telescope’s senior project scientist, accepts that the project’s delays have an exoplanet-shaped upside. “The surveys have been done, and we have our list of transiting exoplanets, and we wouldn’t have had that list even a few years ago. That’s a pretty clear benefit of being late,” he tells Physics World.

The JWST’s main exoplanet task will be to probe the atmospheres of the planets as they pass between the telescope and their parent stars. During these transit events, the atoms and molecules in the exoplanet’s atmosphere will absorb some of the light from the parent star, creating tell-tale gaps in the star’s spectrum that the JWST can detect. And thanks to that painstakingly compiled target list, Mather says, they won’t have to be lucky to spot one. “We now know where to look for transiting exoplanets, and exactly when to look,” he says.

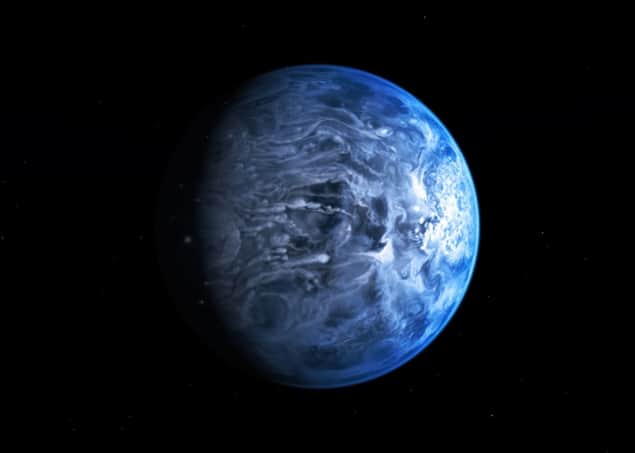

One of the worlds that will fall under the JWST’s gaze during its first cycle of science observations is the hot, rocky planet LHS 3844b, which could harbour the first known volcanoes outside our solar system. Then there’s 55 Cancri e, a super-Earth with “weather” that may include lava raining from the sky, and HD 189733b, a hot, Jupiter-like planet that may have clouds and rain made from vapourized minerals. Astronomers are also keen to study a relatively young exoplanet, CT CHa b, which may be surrounded by a disc of gas and dust that is gradually accreting onto its surface.

A further target is the TRAPPIST-1 system, which consists of seven terrestrial exoplanets orbiting a red dwarf star 40 light-years away. Astronomers are planning to use the JWST to scrutinize this system in several ways, including a general reconnaissance of all seven worlds and two sets of observations on its third planet, TRAPPIST-1c, which may be in the system’s so-called habitable zone, where conditions may allow water to exist as a liquid on or near the surface.

With many of these transiting, habitable-zone planets, the JWST will be looking for biomarkers – the absorption signatures of oxygen, water, carbon dioxide, ozone, methane and indeed anything else that could be produced by living creatures or indicate a potentially life-supporting environment. But the telescope’s exoplanet studies will go deeper, too. Using its infrared instruments, the JWST will peer into the dusty confines of star-forming nebulae and circumstellar discs around young stars, collecting data that should give scientists a better idea of how new planetary systems form.

The ten-billion-dollar gamble: How the JWST will see deep into the universe’s past

Given that planets beyond our solar system weren’t really on the menu when the first conceptual studies for the JWST were drawn up in the mid-1990s, it’s fair to say that the telescope’s mission has undergone a significant shift. “We did not even know there were exoplanets when we started work on Webb,” Mather notes. “People were just starting to make the first observations of them, so we asked, how can we use Webb to see them?”

Today, nearly one-third – 70 out of 286 – of the science proposals chosen for Cycle 1 of JWST operations are related to exoplanets. The telescope’s long delays have been a headache for astronomers and NASA administrators alike, but they have also changed its mission beyond recognition, making what was once a side-line into a priority for the largest telescope ever launched into space.