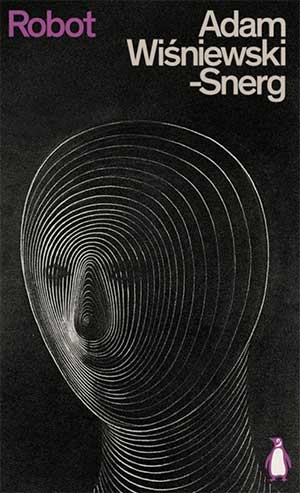

If reading Adam Wiśniewski-Snerg’s Robot (Penguin Classics, 2021), translated by Tomasz Mirkowicz, makes you think about Stanislaw Lem’s work, you’re not alone. Indeed, both Robot and Lem’s His Master’s Voice (published in Polish just a few years apart) take up the fascinating but insoluble problem of whether or not we’re alone in the universe.

If reading Adam Wiśniewski-Snerg’s Robot (Penguin Classics, 2021), translated by Tomasz Mirkowicz, makes you think about Stanislaw Lem’s work, you’re not alone. Indeed, both Robot and Lem’s His Master’s Voice (published in Polish just a few years apart) take up the fascinating but insoluble problem of whether or not we’re alone in the universe.

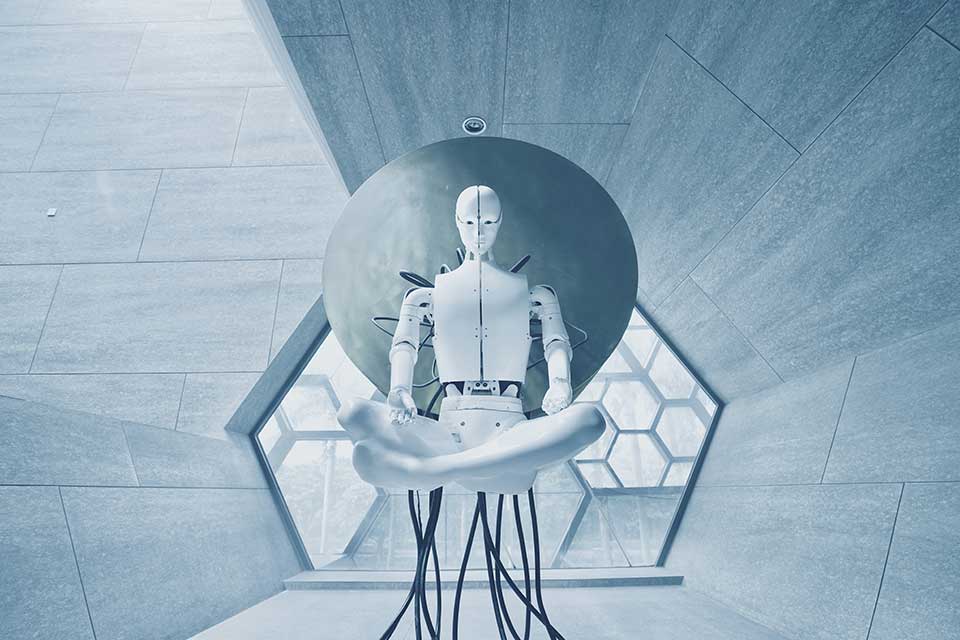

One might even call Robot surrealist science fiction and liken it to Kafka’s work, or even Lem’s Memoirs Found in a Bathtub, since the main character spends most of his time wandering around the halls of an underground shelter, unsure of his own identity and his place in the community that has formed following an apocalyptic event on the surface. His identity confusion derives from his “birth” on an assembly line under a kind of bell jar. Given instructions by a mysterious Mechanism to study the people living in the shelter, the protagonist proceeds as if he is a living machine given a modicum of free will (as explained by the Mechanism).

Much of the novel focuses on the protagonist figuring out why those around him are living underground and why many of them believe that he is a physicist named Poreyra. Encountering strange “statues” that weigh several tons in one of the shelter’s rooms, he eventually moves through a mirror there into a replica of the stricken city, where time moves at a fraction of the speed experienced in the shelter. Did an alien species descend on the city and slow time down there, but not underground, where many had fled when the strange alien-looking sphere appeared out of nowhere? And why does the protagonist encounter doubles of the people he meets? Is the shelter not even on Earth anymore (as some of his acquaintances insist) and moving out of the solar system at an incredible rate? If so, why and what do the aliens wish to learn about the humans within? And, most importantly, is the protagonist himself a robot or a human being?

Questions like these raise Robot to a stylistic and philosophical level rarely seen in science fiction.

Questions like these raise Robot to a stylistic and philosophical level rarely seen in science fiction. Wiśniewski-Snerg’s narrator tells us from the beginning that the protagonist was “created” and given instructions, but those instructions may or may not be his free will talking. He must make his way in his new life by taking confusing cues from the people around him, and he isn’t even sure what his actual purpose is. If that isn’t a summary of what it means to be a human being, I don’t know what is.

The protagonist’s later discussion with a colleague about evolution, the food chain, and alien intelligence also asks us to think more broadly about our place in the universe. Is the relationship humans might have to higher beings no different than that between, say, ants and humans? Could humans ever actually think outside of their perceptual box? Like Lem, Wiśniewski-Snerg seems to think not. Questions like these, though, invite us to consider our perceptions more objectively and think more purposefully about what it means to be alive.

Madison, Wisconsin