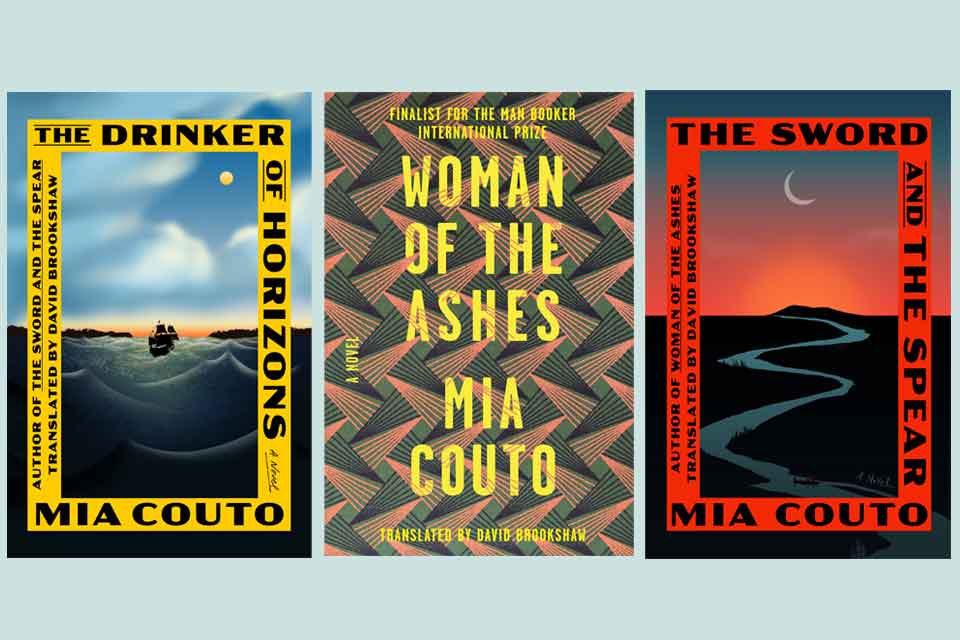

Just published in March, The Drinker of Horizons (translated by David Brookshaw) brings to a close Mia Couto’s captivating Sands of the Emperor trilogy: The story of late nineteenth-century Mozambique seen mainly through the lens of a love affair between Imani, a young, mission-educated VaChopi, and a Portuguese sergeant named Germano de Melo. It’s a many-layered tale of cultural and political clashes—between the Portuguese army and the emperor Ngungunyane, but also between African states themselves—which culminates in an epic voyage into exile for both Ngungunyane and Imani aboard a ship called África.

As in all his works, Couto—winner of the 2014 Neustadt International Prize for Literature and a finalist for the 2015 International Booker Prize—conjures up a vivid, incantatory portrait of his homeland, where competing visions of life and meaning battle for supremacy. “I don’t see with my eyes,” says Dabondi, one of Ngungunyane’s many wives. “I see with my dreams.”

Anderson Tepper: Tell me about the scope of the Sands of the Emperor trilogy and what you wanted to examine about the Portuguese colonial story in Mozambique.

Mia Couto: I revisited the last years of the existence of one of the greatest African empires, led by an African emperor named Ngungunyane. He inherited from his grandfather Sochangana a territory three times the size of Portugal. The colonial government had no alternative but to live with this territory governed by an African, which was given the name the State of Gaza and with which the colonizers maintained a relationship full of tension but respect. The story is focused on the period around 1895, the year this empire was overthrown by the Portuguese army.

Tepper: The chapters alternate between Imani’s point of view and the letters of Germano de Melo and other characters. How did you decide on this structure?

Couto: It seemed to me that the narration should be in the voice of a woman who came from the culture of orality but who was situated in a kind of border zone between two worlds. By an exceptional set of circumstances, Imani had mastered writing and the Portuguese language. Hence, she was chosen by both conflicting parties as a translator. The Portuguese discourse emerges in the realm of writing and in the form of letters to better reveal the rigid and hidden picture of these foreigners. Even though they were in African territory, they were from far away and their voices came through the written word.

Tepper: What were the challenges of writing a historical work compared to your other books set in contemporary eras? How much of the real figures did you want to capture faithfully, and how much did you choose to invent or interpret?

Couto: The story of this emperor is well known in Mozambique and Portugal. For contradictory reasons, his figure served both Portugal and Mozambique as the center of campaigns to raise the morale of opposite regimes. Mozambicans who fought for their country’s independence chose the emperor as a symbol of nationalist resistance, which was not true. Ngungunyane never had a project called Mozambique. He defended his part of the territory against Portuguese interests but within the framework of a conflict between two emperors. In his government he did what all emperors did: he used force, slaughtered, and enslaved many people.

On the other hand, Portugal also mystified this enemy who, when he was captured, was already defeated by conflicts within his court. It was necessary to create greatness in this defeat to lend international glory to the victory of the Portuguese. We are, finally, facing a curious refabrication of two pasts, and this provides precious material for literature.

Tepper: There are several major examples of trilogies in African literature, from the works of Chinua Achebe and Nuruddin Farah to Tsitsi Dangarembga and Patrice Nganang. What was it like for you to work on such a large project?

Couto: When I started to write the novel Sands of the Emperor, I didn’t think that I would write a trilogy. It was the narrative itself that dictated to me how much this story should tell. It became clear that the narrative would be based on three moments: that of the land, the rivers, and the sea. And in that way, each of the three books was built. Ngungunyane was captured in the capital where he reigned. He was taken by rivers and seas to Portugal, where he was publicly displayed as a trophy of war. Ngungunyane belonged to a culture in which the sea was a forbidding and nameless place. And he ended up dying in exile on the Atlantic island of Azores trapped by that immense ocean. He lived surrounded by his hundreds of wives but spent the last few years without the presence of a single woman with whom he could share memories.

Tepper: From the beginning, your writing has been imbued with an extraordinarily rich, poetic quality—what critics tend to call “magical.” But it seems very much rooted in Mozambican reality and worldviews. Tell me more about the sources you drew on for your distinctive language and perspective.

Couto: To reconstruct the environment of the Portuguese, I resorted to a wide variety of written documents. There is an enormous source of books, letters, and reports. The defeat of this African emperor was one of the most glorified chapters in the history of Portugal. In contrast, written sources are poor and scarce in Mozambique. What I did was travel to the places where the oral memory of the presence of this empire is best preserved. What is interesting is that much material was obtained through songs and dances that are performed to this day and that refer to the feelings of those, among Mozambicans themselves, who were dominated by his rule. For these Mozambicans, it was clear that African colonization does not always have to be carried out by a European power.

Tepper: How did you envision the character of Imani and her complicated sense of allegiance and belonging? More than just a translator, she sees herself as a “bridge” between cultures. As she says, “I spin a web that joins the different races.”

Couto: Imani seeks to harmonize her different interior universes. She speaks several languages and is fluent in Portuguese, which is the language that—paradoxically, as a second language for the vast majority of Mozambicans—works most to unify the nation. In a certain sense, Imani represents what Mozambican writers are today. They act as translators not just of languages but of worlds. It’s not just a language issue. There are borders—which are always organic and fluid—that separate orality from writing, and the different representations and cosmogonies that understand time, the body, and death in different ways. Literature is one of the main bridges to engage these narratives in dialogue.

In a certain sense, Imani represents what Mozambican writers are today. They act as translators not just of languages but of worlds.

Tepper: In a recent article in the New York Times, you describe how Mozambican writers are helping create new myths and build the foundations of a unified country: “We are still in the process of creating one nation; one nation that can bring together these different languages, different beliefs. We are substitutes for the prophets.” What does this literary landscape look like today, and are you encouraged by what has been accomplished since independence?

Couto: There is clearly a parallel path between the creation of a Mozambican literature and the nation. As a young country, Mozambique has an almost obsessive fear of anything that might harm the achievement of national unity. But this unity cannot result only from a political statement. You have to work deeper. The bridge between cultural, ethnic, and linguistic differences is made with the help of literature, which creates a narrative connecting two worlds: one nocturnal and lunar and the other diurnal and solar.

There is clearly a parallel path between the creation of a Mozambican literature and the nation.

Many of the Mozambicans who live in the universe of modernity still folklorize traditions or are ashamed of what we can call the most ancient cosmologies and religiosities. By day, they are Catholic or Muslim. At night, they indulge in so-called traditional ceremonies and beliefs. There is an expression called “husbands of the night” to designate the hidden lives of couples and lovers. Literature helps create a more open and committed relationship between these diverse worlds that most Mozambicans inhabit.

At the same time, literature can also help visit a past that was never made of pure essences and, on the contrary, was always mestizo and made up of exchanges between African peoples among themselves and between them and those who came from outside.

March 2023