The United States is expected to play a supporting role in an international campaign to monitor greenhouse gas emissions from space.

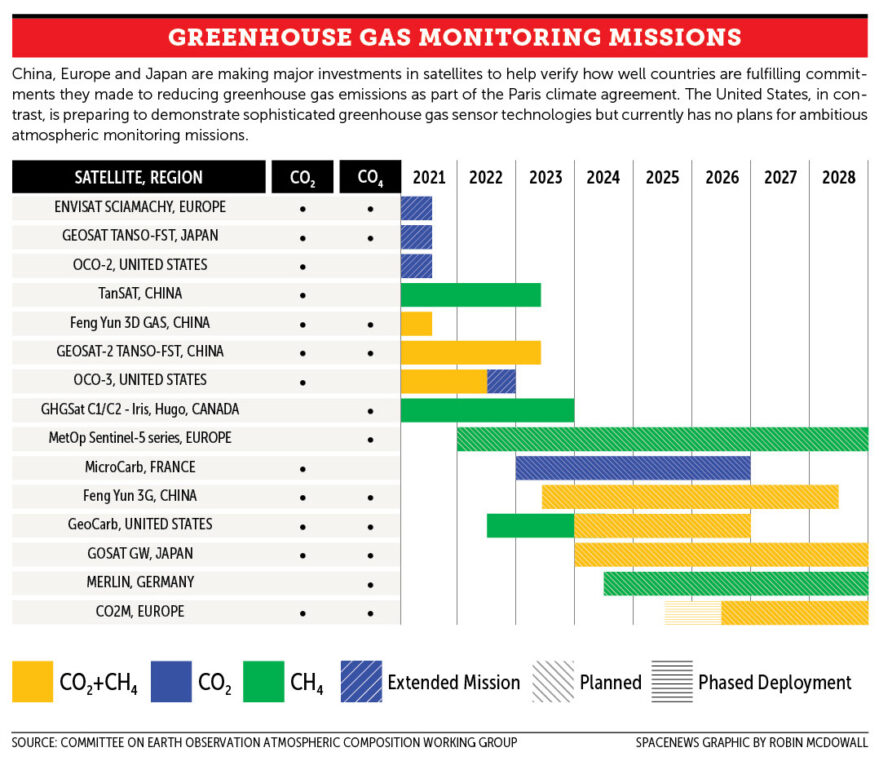

Through the Committee on Earth Observation Satellites, nations are coordinating efforts for space-based monitoring of air quality, greenhouse gases, the ozone layer and natural climate drivers like solar energy. China, Europe and Japan are making major investments in satellites to help verify how well countries are fulfilling commitments they made to reducing greenhouse gas emissions as part of the Paris climate agreement.

The United States, in contrast, is preparing to demonstrate sophisticated greenhouse gas sensor technologies but currently has no plans for ambitious atmospheric monitoring missions.

“Other countries are making great contributions and pushing as hard as they possibly can,” said David Crisp, a NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory atmospheric physicist helping to coordinate efforts to track carbon dioxide and methane by the 34 space agencies that make up the Committee on Earth Observation Satellites. “We are relying on their contributions. There’s no way around that at this point, but I would like our country to lead.”

Through the Paris climate pact signed in 2015, 174 countries and the European Union agreed to take steps to mitigate global warming and report their progress in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Those reports, called the global stocktake, are due every five years beginning in 2023.

NEW PRIORITIES

The Trump administration announced plans in 2017 to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement and did not support greenhouse-gas monitoring initiatives. It’s not yet clear whether that work will get a significant boost from the Biden administration.

Hours after taking office, President Joe Biden signed an executive order recommitting the United States to the Paris Agreement and Biden often refers to “tackling the climate crisis” as one of his top priorities.

Still, there are many ways the federal government works to address climate change aside from monitoring greenhouse gas in the atmosphere.

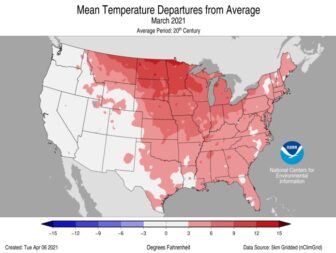

NASA develops and demonstrates technology to monitor the ozone layer, air pollution, ocean chemistry, and changes in sea and land ice. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration provides long-term monitoring of those conditions in addition to offering extensive observation of global temperatures, precipitation, ice and ocean conditions.

NASA OR NOAA?

Experts disagree on whether greenhouse gas monitoring is a job for NASA or NOAA.

“NASA is the pathfinder,” said Barry Lefer, NASA’s Tropospheric Composition Program manager. “We build the first one, prove that works and then we hope that there are NOAA follow-ons.”

NASA, for example, proved it could measure carbon monoxide in the troposphere with the Microwave Limb Sounder on the Aura Earth observation satellite launched in 2004. NOAA now provides similar data with the Ozone Mapping Profiler Suite on the Joint Polar Satellite System.

Monitoring carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is trickier. To provide the global stocktake reports mandated by the Paris Agreement, the United States would need to measure atmospheric carbon with great precision and high spatial resolution.

“NASA is probably the only agency that could build that system,” said Crisp, who was the principal investigator for NASA’s first carbon dioxide monitoring mission, the Orbiting Carbon Observatory. “However, once built and launched, it could be delivered to NOAA for use as an operational system.”

Europe plans to make weekly, global measurements of methane and carbon dioxide with the two-satellite Copernicus Anthropogenic Carbon Dioxide Monitoring, CO2M, mission. Japan plans to make similar observations with its GOSAT satellite series as does China with its TanSat satellites.

Neither NASA nor NOAA have similarly ambitious programs underway. That could change if Congress approves the Biden administration’s plan to increase NASA and NOAA budgets.

BIDEN BUDGET

The Biden budget blueprint calls for adding $1.4 billion to NOAA’s 2022 budget partly “to expand its climate observation and forecasting work and provide better data and information to decisionmakers.”

The new administration also proposes a 12.5% increase in NASA Earth science funding, or about $250 million above 2021 levels “to initiate the next generation of Earth observing satellites to study pressing climate science questions,” according to the budget summary released April 9.

It’s too soon to say how the agencies would spend the money.

NASA funding could be directed toward a series of missions recommended in the 2017 Earth Science decadal survey to determine how Earth’s climate, water cycle, soil and vegetation are changing. The decadal survey also mentioned greenhouse gas monitoring as an option for a future Explorer-class mission, but little has been done to flesh out that concept.

Instead, NASA is continuing to gather data with atmospheric sensors in orbit and demonstrating new technologies to measure greenhouse gases.

Two NASA sensors are scheduled to travel to geostationary orbit as hosted payloads on commercial satellites within two years.

The Tropospheric Emissions: Monitoring Pollution sensor, or TEMPO, is designed to provide hourly pollution reports for North America with a resolution of 10 square kilometers during the day.

“If things happen like hurricanes or fires, we can look at part of the field of regard more frequently,” said Kelly Chance, TEMPO principal investigator at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. “For example, we can observe a sixth of North America every 10 minutes.”

Geostationary Carbon Observatory, or GeoCarb, is a staring sensor to track atmospheric carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and methane over North and South America.

NOAA plans to include an instrument similar to GeoCarb on its next generation of geostationary weather satellites scheduled to begin launching in the early 2030s.

For now, NASA identifies CO2 sources and sinks with the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 launched in 2014 and the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-3 mounted on the International Space Station in 2019.

OCO-2 and OCO-3 were designed to show that NASA could make measurements from space with the necessary accuracy and precision to monitor global carbon dioxide emissions in areas roughly the size of Texas.

Based on that criteria, the sensors have been extremely effective. To verify Paris Agreement emissions targets, though, the United States would need a satellite constellation offering higher resolution data and greater global coverage.

COMMERCIAL DATA

Could the private sector play a role in making those observations?

“The technology is here today to do that kind of work with very small satellites,” said Charles Beames, chairman of the SmallSat Alliance. “Startups with ambitions to do that are in various phases of fundraising. Frankly, I think the government needs to either buy commercial satellites or buy the data, whichever is in their best interest.”

Commercial small satellites tend to focus on detecting methane rather than carbon dioxide.

“Atmospheric CO2 has a long lifetime,” said Ken Jucks, NASA Upper Atmosphere Research program manager. “You need a very precise measurement because the new CO2 emitted during a particular hour produces a very small change in the total amount of CO2.”

Canada’s GHGSat is identifying important methane sources with 15-kilogram satellites. MethaneSAT LLC, a subsidiary of the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund, is preparing to launch a 350-kilogram satellite in late 2022 or early 2023 to pinpoint faint methane emissions from oil and gas fields.

All the publicly and privately funded satellites have roles to play in the global greenhouse gas observing system, Lefer said.

Japan’s GOSAT-2 measures CO2 and methane within 10-kilometer-diameter areas that are separated by about 150 kilometers. The Tropospheric Monitoring Instrument on Europe’s Copernicus Sentinel-5 Precursor satellite obtains global, daily observations with 49-square-kilometer resolution.

When those satellites detect atmospheric methane, they can share the data with GHGSat, which can pinpoint sources down to 50 square meters, or MethaneSAT, which will offer 1 kilometer resolution.

UNCERTAIN FUTURE

Beyond TEMPO and GeoCarb, NASA has no greenhouse gas missions underway.

“It’s to be determined what NASA’s next move is going to be after GeoCarb,” Lefer said.

If Crisp could chart the course, he’d encourage the United States to gather and share global greenhouse gas data like it does weather data.

“If we add a U.S. system to the European and Japanese systems just like we do for weather forecasting, we might even get China to share its contributions,” Crisp said. “Once we get some big players involved, there’s more incentive for everyone to share data.”

This article originally appeared in the April 19, 2021 issue of SpaceNews magazine.