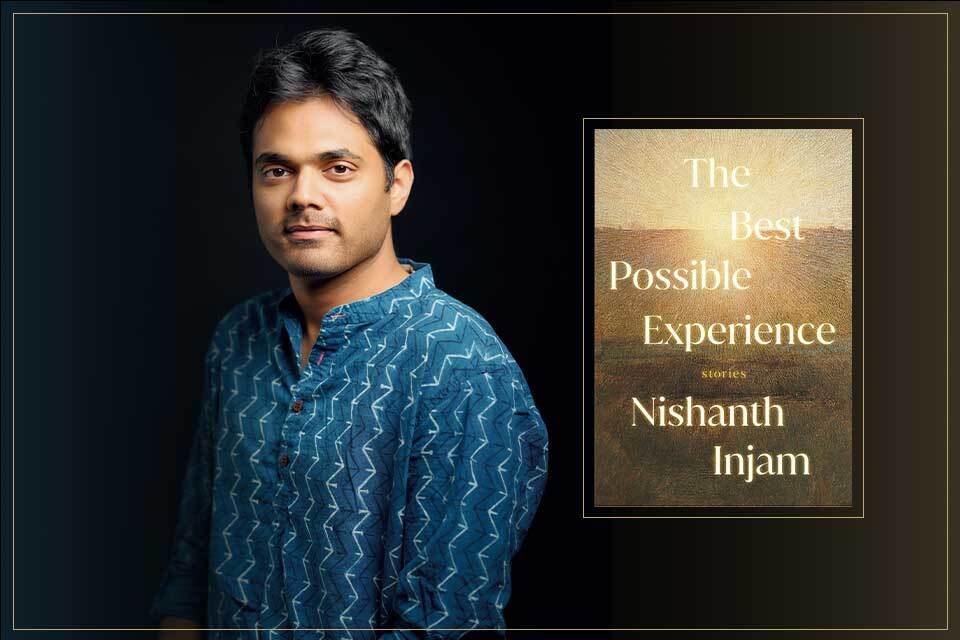

Born and raised in Khammam, a small town in the state of Telangana, India, Nishanth Injam published The Best Possible Experience, his debut short-story collection, in July 2023. He immigrated to the United States in 2011 as a graduate student in computer science at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. With his MS in hand, he moved to the Midwest in 2011 to work at the Chicago Tribune as a software engineer. In 2014, restless and discontent in the tech industry, he enrolled in an online Stanford University continuing-studies course in creative writing, where the encouragement of his instructor, Suzanne Rivecca, as he says, “changed my life.” She recalls him as “a person for whom the act of storytelling felt innate and deeply urgent, maybe even sacred.” She describes the eleven stories that make up this powerful exploration of the meaning of home and belonging as having “that ineffable quality—that sweet, piercingly human spot between faith and despair.” In 2018 Injam was accepted into the University of Michigan’s Helen Zell Writers’ Program, where he received his MFA in 2020. His awards include the PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for “The Math of Living” and the Cecelia Joyce Johnson Emerging Writer Award from the Key West Literary Seminar. Currently working on a novel that is a prequel to the stories in this collection, he lives in Chicago with his wife, Meghana, and his son, Saavi.

Renee H. Shea: The New York Times called The Best Possible Experience (Pantheon Books, 2023) “a stunning debut.” Acclaimed writer Nana Kwame Adjei Brenyah praised the collection as “an epic mosaic of life.” Your Indian colleague Megha Majumdar said that reading these stories “made me want to cast all else aside and return home.” How are you feeling about such high praise?

Nishanth Injam: Grateful and lucky . . . thrilled. But mainly I’m in a place of stunned disbelief that all this has happened!

Shea: How did it happen? You’ve said that graduate school in Philadelphia and your job as a software engineer in Chicago was a time of despair. “Desperately unhappy” is how you’ve described yourself. You’ve also said you weren’t much of reader of literature, preferring Marx and Schopenhauer. So what brought you to a creative writing class?

Injam: You have to understand the context. I was away from family; I was lonely. All my life I had been told I should be an engineer, make money, sort of be the savior of my family by becoming the breadwinner, paying off debts, leading us to a better life. I thought computer science was the answer, and all along I hated it. But the material reality of me not enjoying it was never something I gave consideration to. I knew I had to do this to be able to help my family.

I moved to the US with a huge student loan from India, 15 percent interest. I somehow graduated [from the University of Pennsylvania] and got a job. Initially, I was just trying to make sure I wouldn’t get fired: I was on a visa that made even switching to another job difficult. My life seemed bleak and unbearable. I needed an outlet, a way to create an alternative world where I could find meaning, but I didn’t know what that was. On pure whim, I signed up for this class. I didn’t know anything about short stories or even about grammar, since I was not writing in my mother tongue. Suzanne [Rivecca] was such a kind and brilliant teacher. She never judged the fact that, for instance, my tenses were all over the place; she saw past that and recognized that I was trying to construct a complicated story that had some beauty in it.

Shea: I understand that you wrote the stories that became The Best Possible Experience over seven years, and they became your MFA thesis. In an interview you said that your adviser, Peter Ho Davies, told you that something was lacking to make them a collection. You didn’t disagree, but it took you over two years to complete another story. Could you talk a little more about that experience?

Injam: When I finished my thesis in 2020, my adviser said these stories are all good, but the collection as a whole was missing the mother figure, the mother-child story; there are several father-son stories. As soon as he said that, I knew he was right, and I also knew that to write it, I would have to go deep into my relationship with my own mother, who had recently died.

From this place of grief, words had lost all meaning for me. Every story would sort of start promisingly, and then all those drafts would fall apart at page four or five. I’d spend months trying to coax them back to life. I think it was too hard for me to attack the problem directly. Any time I would write about missing a mother, I would lose emotional control of the narrative. Finally, I decided it just wasn’t working. Then, as I was writing one day for fun about this small village in Telangana, the story became “The Zamindar’s Watch.” I was writing about a teenage girl and Zamindar, and the girl had a mother. Eventually as I kept writing, I realized that the story was really about the girl and her mother.

That turned out to be the piece that I needed. I think it’s easy to write about a mother and child relationship, but I didn’t want to do just that. My mother is very special to me, not only because she was my mother but because she was capable of understanding me in ways that seem outside the realm of being a mother. I wanted to capture that uniqueness. Once I gave the manuscript to my agent, it sold within two months.

From this place of grief, words had lost all meaning for me.

Shea: Did you choose the collection’s title? If so, how did you know it was the right one?

Injam: I knew the title as soon as I wrote that story, “The Best Possible Experience.” As early as 2015 I knew that story would be the philosophical touchstone for the book because it’s not only about storytelling; it’s about why I am engaged in this project. All the stories are told in the service of a larger goal. Like Mr. Lourenco’s Lisa story [in “The Best Possible Experience”], which we find out is false but grounded in true historical context, all the stories in my book are taken from life but are not “truth.” As the writer, I’m telling these stories because I want to affect the reader, shift something ever so slightly inside them. I’m trying to be in communion with the reader because maybe together we can move toward greater love.

Shea: Many of your stories take you—and us as readers—home to India, and it makes me wonder if there are Indian writers who are especially influential to you.

Injam: Arundhati Roy is my favorite Indian writer. I really admire her not only for her political activism but for how compassionate and tender her advocacy for minorities is. She is such an inspiration. The way she led her life made it possible for me to even walk this route. Without her being this inspirational figure, I would not even have known that I could live a meaningful life and fight against structural injustices that are happening around us.

Shea: I’d like to turn to individual stories and craft. Let me start by saying that you have talked about character being your strength—and I certainly agree that you create characters in the sketch of a short story that are as vivid as many developed through a whole novel. But I also see you doing such interesting and complex things with structure. Some stories are structured by time (measured by days or larger expanses), occasionally there are “chapters” that read like vignettes, some simply have marked divisions (###). How do you make decisions about structure?

Injam: I’m glad that you brought that up because I think structure is a kind of secret strength of mine. When I am writing the first draft, I usually know what the structure is; revisions are always a matter of figuring out what sentence doesn’t work, or if there is something that’s not somehow directly serving the story.

When I began writing, I didn’t know what a short story was supposed to do. I wanted to pour the overwhelming loss I felt into containable shapes that would live outside of me. I was trying to write a story that would hold the yearning that I had. Stories were vessels of yearning, of emotion, a way to feel less alone.

I think that the short-story form as practiced in America is contaminated by capitalistic influences. For example, one of the definitions I hear about an ideal short story is that it should be structured as this perfect jewel, a diamond that needs to be cut and cut until only the core remains. That view privileges efficiency and perfect atomization, something the structure of capitalism demands. Anything that cannot be atomized is unnecessary or redundant in some way. It posits a story as a punching machine. The story is a worker who lives and dies by the punch it delivers. Endings are the only appropriate place for the release of emotion, where “meaning” resides, and the reader goes home with a safe little thought they will soon forget. Such thinking is very rigid and subservient—and I want to resist it.

The short-story form as practiced in America is contaminated by capitalistic influences.

Shea: Most of your stories set in India are not in a city—New Delhi or Mumbai, for instance. They take place in small towns rather than urban centers. In what ways are these smaller town settings crucial to your work?

Injam: I grew up in this small town in Telangana, four and a half hours away from Hyderabad. I was there for the first eighteen years of my life until I went to undergrad near Delhi. There’s something about small towns that animates my imagination; maybe it’s a function of growing up in a small town, a village, or maybe I like a smaller stage from which I can observe the characters in the story. In a big city, it feels like there is the larger world that imposes on the characters in ways that are unpredictable, whereas in a small town or village, there is greater control over what might happen or things that might intrude upon the lives of these characters. Again, it’s cutting to the emotional core of the characters.

Shea: I find your use of third-person narration especially interesting. For many writers, it’s the default, but for you, it seems to have more complicated purposes. For instance, in “The Immigrant,” third person enforces a distance, a detachment. In “The Best Possible Experience,” third person seems to hold readers at bay in ways that hearing the perspective of either the father or son might simplify. In “Summers of Waiting,” third person gives us glimpses of intimacy. Am I on the right track here?

Injam: I think it comes with the voice. In “The Best Possible Experience,” I started with the scene on the bus and the magnificent rock, the humor. When I’m writing the story, I’m usually telling it to myself, so the person who was writing the story was telling it to me. In “The Immigrant,” it came from the consciousness of the immigrant; the third-person narration is adjacent to that consciousness.

“Summers of Waiting,” which is in many ways the heart of the book, comes from a place of yearning, to reconnect with the grandfather, to be home, even though she knows, in some ways, she cannot be with him: one, he’s old, and, two, she has to go back. This rupture has happened in her life, but she can’t help but wish for them to be reunited. The third-person narration allowed me to switch points of view and get into the perspectives of both characters. But it’s not about getting into the heads of the characters, or I’d have chosen dual first-person narration.

I was trying to use the narration to get to the heart of the relationship between Sita and Thatha. Sita has a purpose within the pages of the story; Thatha does not. It’s not equally balanced, but there’s an emotional weight in their lives that makes them who they are. Fundamentally, I want my third-person narratives to reflect the spirit of the story: I think of it as syntax at a story level.

Shea: “The Bus,” the first story in the collection, feels to me like an outlier, though not exactly sci-fi, as some have suggested. A man is talking to his dead brother, but not in a sci-fi or ghostlike kind of way. Isn’t it more about the disorientation or dislocation that accompanies grief—and about disappearance?

Injam: It’s definitely an outlier. I wrote it ten days before my mom died. It was almost a premonition that I was going to be in that space. The whole collection is in some ways a journey that I have gone through over the years, though in writing about myself, I hope it will act as a mirror for others. For a large part of my life in the States, I was worried that I would get a call and would lose the tenuous thread that’s home. My home was in so many ways already essentially gone—except that as long as my parents were alive, I still had a home to go back to. That was keeping me anchored and giving me hope to lead my life every day. I was afraid it would be taken away from me. It got to a point where my fear became true when my mom died.

It’s almost as if I was writing in some ways to prepare myself for the very things I knew would happen, the eventuality that someday death is going to come for the people we love. I’m still obsessed with the question of how we can lead a life in which we don’t have the person or persons we love. The way I see it is that as I am moving from this place of having a family who is far away, and now losing them to time, to death, I’m losing myself along the way. I’m basically this rocket ship that is losing parts and parts every day. So, what’s going to happen after that: What do you do when you have lost everything you care about? Whom do you talk to? Then the question becomes, Why can’t we keep talking with the people we love?

What do you do when you have lost everything you care about?

Some of that thinking went into “The Bus.” It’s not that I was wishing this reality into existence. It was just a way for me to prevent the irreversible from happening and also to make space in which I could freeze some of the existing conditions of my reality—almost preserving time capsules of the love I had and wanting to make it last forever. Talking to the dead brother comes from that place.

Shea: But you never had a brother?

Injam: No, I’m an only child. The story’s question is, If my people are gone, whom can I talk to?

Shea: Were you thinking of Indian (those living in India or others who had immigrated) readers as you wrote the stories? Why might a young, lonely immigrant (such as you were) find solace—or company—in these stories?

Injam: That’s a brilliant question. I really wish it would be a solace. I really wish I had read these stories before I moved to America. Maybe that’s partly why I wrote them. I don’t know, though, if I had read them whether I would have chosen a different route. I don’t believe in reading as a way of transferring knowledge or as way of empathy. I believe in reading as a way of deepening the ocean, the ocean that lives in each of us.

I believe in reading as a way of deepening the ocean, the ocean that lives in each of us.

Shea: In a recorded discussion at the Chicago Public Library, you said that during a time of despair you wrote the book (and I’m paraphrasing here) “to keep my country, my family, the home I knew next to me. It was wanting that sense of home that pulled me to writing. Over the years, that desire transformed into a way to open up my home and share it with others. It was like building a castle with no walls.” That’s a powerful image of how the stories allow you to reach out by reaching inward. Is that how you see it?

Injam: I think about how I was back in India and then how I am now in America. I used to have five senses when I was in India, and now I only have four senses. I’ve permanently lost part of myself. So I don’t have the ability to be fully at home with my past self. Ilya Kaminsky wrote a poem, “Elegy for Joseph Brodsky,” that opens: “In plain speech, for the sweetness / between the lines is no longer important, / what you call immigration I call suicide.” In some ways my moving to America was a suicide for my previous self. There’s a new self that’s emerging now, but the fact still remains that I will never be at home in this country. I’ve been living in America for almost twelve years, and it still doesn’t feel real to me. Chicago doesn’t feel real to me. The texture of these places doesn’t feel real to me. It feels as if part of me has been cut off and then transposed into this scene.

I’m trying to be at home, to make a family, but I think it will always be this in-between place. So, because I don’t have a home in the full sense, I am going to create a home on the page that will house me in the fullest sense, but I’m also trying to build a home that is not just for people like me. I’m going to take advantage of this stripping away and the fact that I am already a lost cause in that department. I want then to take the rest of my life that I have and use it to build a home—a castle without any walls, without any restrictions, and make it as loving a place as it can be. If I could do that, it would be a life worth living.

Shea: You have said that at as twenty-two-year-old coming to the US, the moment you walked through immigration at the Philadelphia International Airport with authorities examining your documents and asking questions, you knew you had made the worst mistake of your life. At this moment in time, with your wife and son, one book being well received, another on the way—do you still think it was “the worst mistake”?

Injam: In some respects, I still do; I can’t wish that away. At the same time, I’m grateful for the good things that have come my way. I’m in a place where I’m experiencing a kind of rebirth. It’s almost as if I’m growing up with my son. He’s only two, but this is the real place for him. As he grows up in the suburbs of Chicago, I’m finding myself learning to see this place as a home in some capacity. And I’m trying to enjoy it. But there will always be an underlying current of my true life being on the page.

Summers of Waiting (an excerpt)

by Nishanth Injam

It was summer again. Dust flew to greet Sita’s eyes as she stepped off the flight. In the taxi that would take her home to the village, heat shot through the car window, singeing her skin. She held her forearms against the sun. The last time Sita had been in India, her grandfather had been eighty-two. “I am ready,” Thatha had said in a moment of clarity, the blood pressure monitor she brought from the States listening to the dictates of his heart. This time, a year later, she hoped she’d reach home before it was too late: not the village, not the house, but Thatha.

When she was in the States, they never spoke. He said he couldn’t hear her over the phone. The only time they’d spoken on the phone had been when she’d first arrived as a college freshman. Thrice, she’d told him that she’d landed in Chicago. In return, she’d heard a barrage of hellos, a silence, and a beep of disconnection. From then on, it was Manga, the maid, who answered, who told her how he was. It wasn’t much different when Sita came home either; he barely spoke. Not for any one particular reason. It was the sort of distance that opened up between people who loved each other so much that they had to let each other go.

Except Sita didn’t let go. Her parents had died when she was a child, and Thatha was all she had. Twelve years had passed since she’d first left home for a boarding school in Hyderabad, six of those years in the States, and she’d come back to the village every one of those twelve summers, but all that heat had done nothing: Thatha stayed cold.

The taxi honked past other vehicles exiting the terminal. Sita felt her stomach churn. This was maybe her last opportunity to speak with Thatha. Manga had told her how much Thatha had deteriorated in the past year. He was even less coherent than before; his hands shook so much that he couldn’t be trusted to hold a glass of water. He’d need somebody to watch him in the evenings after Manga cooked and left. Sita wished she could stay with him until the end, but she couldn’t afford it—she had debts to pay, high-interest college loans. She appreciated a lot about the States, had even managed to make a couple of friends, but being there felt like exile. Even in the smallest of things, she felt it. When she was growing up, she’d barely noticed the detergent bar they used in the village, a local brand smelling of soapy citrus, but in the States, she’d come to miss the smell—the fruity artificiality of it. She’d tried to order it online but couldn’t find it. There were days when she would arrive at her apartment, tired from working, and relax by searching for soap on the internet. The other bars, she quickly found, weren’t artificial enough. Part of her knew that she would never find the soap in the States, that she would find it only in the village, but she continued to look to the point where the only ads she got in her browser were for detergent.

The taxi bustled through the traffic, moving past city buses and motorcycles and auto-rickshaws. Sita’s eyes fell on the billboards on top of the buildings. Advertisements for fairness creams, motorcycles, action movies. She’d had enough of ads—she worked in advertising operations for a media company in Chicago. It wasn’t the best job; she had only two weeks of vacation per year, and the journey here took two days of that. Twelve days was all she had. Twelve days to be with Thatha. She leaned her head against the window.

Editorial note: Excerpted from The Best Possible Experience, by Nishanth Injam. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Nishanth Injam.