Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

I love alternate takes and extended scenes on DVDs.

It’s a chance for me to see what the movie or show might have been like and to understand the effect of the director’s choices: camera angles, tweaks in the dialog, actors’ performances. The deleted scenes from The Office, for example, are as hilarious as (if not better than) the broadcast versions. The extended scenes for The Lord of the Rings add so much depth to the characters’ relationships. The deleted scenes from Return of the Jedi add a layer of conflict between Vader and the Imperial guards that make him (and the Imperial bureaucracy) more sinister. Outtakes give us a little peek into the shoulda-woulda-couldas of a cinematic universe.

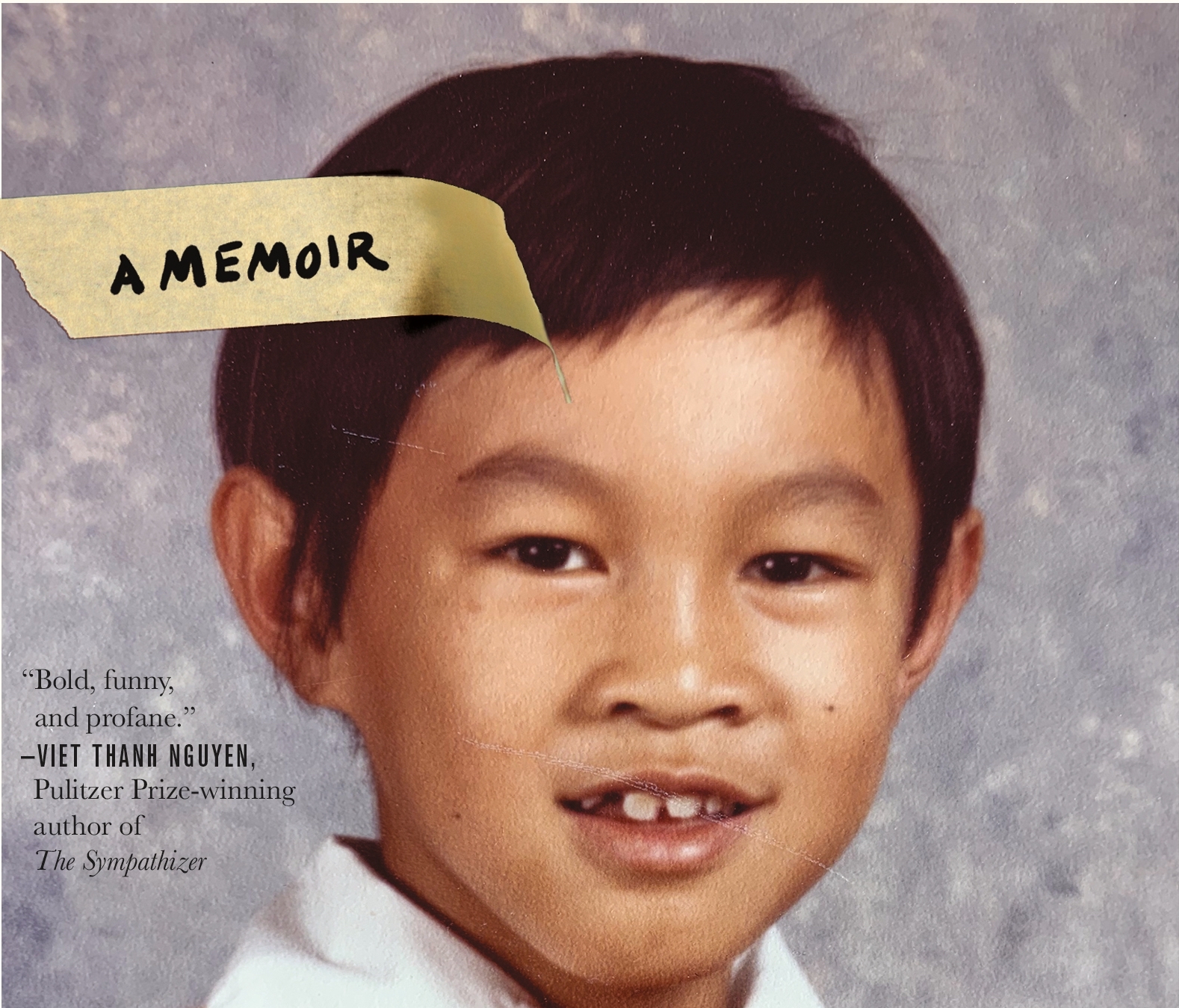

The alternate take rarely happens in real life, but from time to time, you’re lucky enough to see another version (or at least to imagine that you’re seeing another version). This past April, I had the distinct pleasure and privilege of sitting down and chatting (over Zoom) with Viet Thanh Nguyen, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Sympathizer. It was the day before my coming of age memoir’s publication, Sigh, Gone: A Misfit’s Memoir of Great Books, Punk Rock, and the Fight to Fit In, and I had a realization: one of us was the alternate take.

You see, Viet and I are both refugees and our families escaped South Vietnam in 1975. Both of our families ended up at the same relocation camp in Fort Indiantown Gap, PA that summer (along with 20,000 other Vietnamese refugees). Once they left the relocation camp, Viet’s family stayed in Harrisburg, PA for three years before moving to San Jose CA in 1978.

My family was sponsored by some magnanimous Lutherans in Carlisle, PA who helped all twelve of us as we started our lives over. The Trans stayed in small-town PA for two decades, living out the federal government’s deliberate dispersal of Viet refugees to avoid ethnic enclaves. According to the Refugee Dispersion Policy, our separation from other Vietnamese people would accelerate our assimilation (lawmakers specifically talked of avoiding Vietnamese ethnic enclaves). Within a decade, despite the dispersion, many refugees found each other in California, Texas, and Virginia to establish expatriate communities. This was what the federal government was trying to prevent: delicious banh mi and fragrant pho. Hello, Little Saigons! Vietnamese people found each other.

But not the Trans. We grew up without any larger Vietnamese community besides our immediate family, and our Americanization was as swift as it was relentless. In the grand experiment of acculturation and assimilation, we were the control group. Or were we the experiment?

When Viet read an advanced copy of my memoir, he wrote to me: “You gave me a glimpse of what my life could have been like if I had stayed in Harrisburg.” Was I the ghost of Christmas Could Have Been?

As Viet and I spoke in April, I noted that we had scattered from Ft. Indiantown Gap in ultimately opposite directions (I’m in Maine and he’s in California). And that disparateness may illustrate our life’s directions, too: I went to a small liberal arts college, majored in Latin and Greek, and then served a tattoo apprenticeship in New York City. I’ve been teaching Latin and tattooing for 20 years. And Viet? He went to Berkeley, earned his PhD, and won a Pulitzer, so you know…

In 2016, I began writing a memoir about growing up in Carlisle, a project that was ignited by my 2012 TEDx about language and identity. I wanted to present the complexity and contradictions of my experience both within my small town and within my family. I survived (maybe even thrived) with the discovery of both the ‘80s skate punk scene and great works of literature—two seemingly paradoxical guides. But then again, I’m also a Latin teacher and a tattooer.

I may not contain Whitman’s multitudes, but at the very least, I’ve got a duality. I’m the final cut and the alternate take.

—Phuc Tran

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Even before you became a writer you had found other artistic pursuits, like tattooing, which I find completely terrifying. I assume there’s a relationship between your creative interest in tattooing, and your creative interest in writing.

Phuc Tran: Yeah, I suppose so. I’ve been trying to sort of right those two angles—two facets of myself—but other than being deeply grounded in self-expression, I’m not sure if they make a lot of sense, if they’re co-planar. I think they’re facets of myself, and I think I’m okay with that. I love the question, but I haven’t come to a satisfactory arithmetic for how those things connect. It makes me think about Steve Martin and his banjo playing; I wonder what he says when people ask him, like, “Tell us about being a master banjo player and an amazing stand-up comedian—how do those interconnect?”

VTN: I’m actually much more pissed off that he writes books.

We’re complicated people, and there are parts of us that are paradoxical.

PT: Yeah, amazing, right? And then he does the narration for it. You know my thought, Viet, is that we’re complicated people, and there are parts of us that are paradoxical, or not co-planar, and at least part of my writing of the memoir is an invitation to the reader, as well as to myself, to sort of constantly churn in that paradox of who we are.

VTN: So, the memoir, it’s very much a memoir about, you know, being Vietnamese in America, Vietnamese American, Asian American, whatever you want to call it. But, inevitably, there are very explicit markers of identity, subjectivity, and experience in the memoir, about yourself and your family, and so on. The tattooing, from what I can see from your Instagram, is not necessarily related to those autobiographical or personal things. And I’m interested in that because, for those of us that are classified, whether we like it or not, as Vietnamese or Asian American writers or minority writers, the questions of our autobiography and our identity are imposed on us all the time, even if we may sometimes want to deal with them. When you get to visual arts and cultures, of which tattooing is a part, that autobiographical link can be severed. I wonder if that’s true for you, if people see you as the Vietnamese American tattoo guy, or they think, the tattoo artist?

PT: That’s a great question. Tattooing is so interpersonal, since my clients are coming to me with the subject matter that they want already. If they say, “I want a tattoo of a mallard duck,” there’s not any part of my persona, or at least my personal history, that I’m imposing onto that execution of a tattoo of a duck, let’s say.

VTN: So, I’m curious about your relationship to these two kinds of experiences. Not just that they’re very different kinds of creative practices, but that they’re also very different—I assume—psychic spaces, in that sense, with Sigh, Gone, you really had to go deeply into your autobiography, your identity, and all that. Is being a tattoo artist more freeing, or are these just completely different?

PT: I think both. The visual arts are very different from the literary arts, but then also I think it is generally freeing. I think also because Vietnam doesn’t have a long history of contributing to the tattoo aesthetic as much as, let’s say, Japan does. People are coming to me and asking me to do what they want. It’s like being a house painter and you ask me to paint your kitchen purple; I don’t really have a say in that. I just say, “Okay, Viet, I’m gonna paint it purple,” and do the best that I can. It’s a craft, I guess.

VTN: No one ever just comes up and says, “Hey, I want you to do your version of the Sistine Chapel on my body.”

PT: It’s very rare. It’s not, like, omakase.

VTN: (laughs) That would be an interesting concept.

PT: It does happen, and I often will put it back on my client. I take the tattooing very seriously, and I feel like it’s so much responsibility for me to craft something that someone will have to wear forever, in which they have zero input.

VTN: I would find it hard to believe someone would just let you do it without even having an idea, but saying, “Sketch me something, and I can see whether I would want it?”

PT: Yes, for sure, and I always say, “Okay, give me like your top five things that you like, and then I’ll sort of look at that and cull that down to something that I think might be workable.”

VTN: With writing, of course, we learn how to be writers by writing, and we make a lot of mistakes and we graph and all that in the privacy of our own minds, it takes years and years…in your case, it only took four years, so you know…

PT: (laughs) No no, there’s a lot of bad writing in there too.

VTN: But with tattooing, how does it work? The drafting part, like, where does the learning part come in? Who do you work on? Who’s going to let you experiment on their bodies?

PT: Yeah, I mean, it’s very gradual, you start off with simple, foolproof designs, where the margin of error is much wider, and then as you get much better, you take on more complex projects where the margin of error is much smaller. And it’s cyclical; you do a great tattoo and then two weeks later you think you could have done something better. The drafting process happens in the drawing phase of it, really. To me, that’s the most important part of it. You can correct a great drawing that’s been tattooed badly, but you can’t fix a bad drawing once it’s been tattooed, or it’s harder to. When I had an apprentice, I always emphasized that the drawing part was more important for her to learn than the tattooing part. You can’t unlearn bad drawing, I guess.

VTN: Is there a book on tattooing in your future?

PT: (laughs) I don’t know, I’m open to it. I didn’t expect at my middle-age to be writing a book. Would you like to read a book about tattooing?

VTN: Well, of course, I mean it all depends on whoever writes it and does he know how to write a book. Whether that’s an autobiographical book about tattooing or profiles of tattoo artists…isn’t there a bestselling novel called The Tattoo Artist of Auschwitz out right now?

PT: Yeah, that’s right, and John Irving just wrote a book about tattooing also—fiction.

VTN: And now, of course, everybody and their grandmother has a tattoo, so…

PT: Except for you, apparently.

VTN: Did you know that you wanted to write a book, could write a book, or was it just a decision that you made right then?

You can correct a great drawing that’s been tattooed badly, but you can’t fix a bad drawing once it’s been tattooed.

PT: No, I had thought about it… I thought when I retire from teaching and tattooing, I’ll write a book, you know, 30 years down the road. So, there was an idea there. And when I embarked on writing the book, I thought a lot about E. B. White’s injunction to writers, you know: you’re writing for an audience of one. If I’m writing for myself, then the work is going to be more authentic to who I am. I wanted to write the book that I would want to read, and if people get it and they appreciate it, that’s great, and if they don’t, I think that’s okay too. Right out of the gate, I wrote the prologue of the book almost exactly as it is, and I thought, if the agent says, oh this is great I wanna go for it, great, and if not, then that’s okay too. I was fully prepared to not be the right person to tell my story, and I think many people are in that position, as you’ve said, for whatever reason.

VTN: I think a lot of writers, aspiring writers, don’t get that. They want to tell their story, but they have so much anxiety about who they’re telling their story to, or who might be listening in on their story, whether it’s the agent or the editors or whatever, but also if they’re writing a memoir, their own family and friends. Did you feel trepidation about that other audience? You include them in your story, it’s not just your story, it’s the story of all these other people.

PT: I did. I think having a tenuous relationship with my parents gave me, not in a callous way, some freedom and license to be more honest to myself and to my reader than someone else would have. And it’s not that I’m disregarding how they’re going to receive the book, but I’m not as afraid.

Who’s your audience? Do you subscribe to that idea of the audience of one with your writing as well?

VTN: Well, our trajectories are different, because I wanted to be a writer for a long time; I set that goal for myself. I’m the person I describe, who was anxious about my work, and “will I get published, will I get famous, will I get the recognition that I so truly deserve?” Those were disabling thoughts, and so it took me 20 years to get to the moment of simply saying, I’m going to write for myself. I literally thought, fuck it. I’ve written 20 years for other people, and now I’m just going to write for myself. And that was really liberating. I’m not as well-read as you, I haven’t read E. B. White. But every writer that I know, who I think of as having written some kind of important work, has reached that moment, where they decided, the hell with it, I’m just going to say exactly what I want to say, and deal with the consequences later. And that’s a very liberating kind of moment.

PT: And one of those consequences could be not getting published, right, like you’re too weird, or ahead of your time, or out of your step. And that’s okay too.

VTN: I think that’s okay too, it’s easy for me to say, but, for the people who want to be published, it’s pretty hard to live with. And the number of people I’ve met who I would describe as being genuine artists, in the sense of doing exactly what they want to do, and not care about getting published or exhibited or whatever, it’s a very small number of people.

PT: I think for so many people, you’re threading the needle between being true to yourself in the process, and not thinking about your audience in the creative process. But then at some point, there’s a reckoning when you release it to the wider world, and now all of a sudden you’re dealing with the interface of the thing that you created and the audience. I think about the inherent irony to what Thoreau was doing, where he was writing this total loner manifesto, Walden, and then he publishes it! It makes sense, in a larger way, in that he’s talking about this social contract that we need, that we are all interconnected, even if you are an artist and your manifesto is, “I don’t need people, and I’m gonna go live in the woods in this shack…but then, also, I’m gonna publish this book and I really hope people read it.” It’s this paradox that you have to reconcile.

VTN: We’re all stuck in it. For most of us, there’s no way of getting around that. So, the book is gonna come out tomorrow. What are you feeling about it, right now?

I was wracked by this question, ‘Who the hell am I to tell this story? Who the hell am I to be writing this?’ and I figured I’d just go for broke.

PT: I feel really excited. I’ve been in my own echo chamber for so long, with so few readers, and going back to what we were saying about the solitary nature of writing, and then the idea of being able to interact with your readers…I think for better or worse, the Internet has made that interaction with readers so low-barrier now. Anybody can go on Goodreads or Twitter and just tell you what they thought about your book. And, yeah, what little feedback I’ve gotten has been really moving, from people who’ve just said, “I’m so touched by the book,” or whatever.

I think even five years ago when I thought, “Who wants to hear my story?” I had no idea. I don’t want to sound cavalier—I was sort of wracked by this question, “Who the hell am I to tell this story? Who the hell am I to be writing this?” and I figured I’d just go for broke. If my agent and the publisher thought I had a reasonable crack at it, why not? I’d much rather regret having tried to do it, right?

VTN: I’m thrilled to have it. I think that what struck me in reading the book was, from the very first pages, its energy, its unique perspective—which is a polite way of saying that you’re a weirdo.

PT: I appreciate that!

VTN: I read a lot of books by Vietnamese and Vietnamese American writers, and it’s always refreshing to find people who don’t conform. And most of the people who write books don’t conform—but to go way off…

PT: (laughs)

VTN: This book could just be described as a tangent, by most Vietnamese American people. You know, all the wrong things with your life, basically, but it worked out. We need more stories like that, to inspire other Vietnamese Americans—among others—to be weird, to do exactly what they want to do. I go around the country giving lectures, and I meet so many Asian American students and young people who say, “I really want to do something that my parents don’t want me to do. How do I do it?” And I’m always at such a loss to tell them what to do, it’s such a difficult situation to find yourself in. So, books like yours, I think, help to give people permission and an example, not that they want to do exactly what you’re doing, but to break conventions, and to break that family mold.

PT: Which is painful, and there’s a loss there, that’s part of the reckoning, I think, in writing the book—the things you lose in the process of being your own person. That individuation is painful. Thanks for acknowledging that I’m trailblazing for Vietnamese weirdos.