Mine is the story of the woman who thought she was making a book about others; realized only as it was about to be published, that she was the broken one the book talked about. The fragmented, the dispersed, the uprooted.

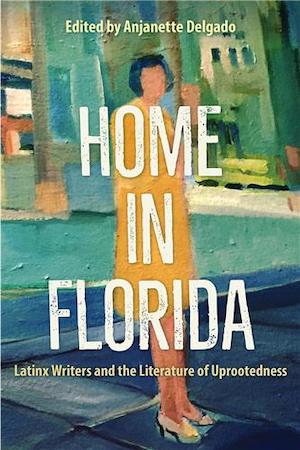

When I was editing the anthology Home in Florida: Latinx Writers and the Literature of Uprootedness, I read and reread the stories of immigrant and bicultural displacement of great writers such as Richard Blanco, Jennine Capó Crucet, Patricia Engel, Amina Gautier, Achy Obejas, Ana Menéndez, Alex Segura, Reinaldo Arenas and Judith Ortíz Cofer but thought, “This isn’t me. I was born a citizen of the country I live in (the circumstances of that, a story for another day), and I’m fortunate to own my home steps away from the foods and language I grew up with.”

But now I know. You don’t have to be an immigrant to know the fear and loneliness of uprootedness. Sometimes life, your own, kicks you out of it. What you had built with so much sweat and love, gone in seconds. An illness ends in loss and suddenly the walls of your own home sport strange shadows. Your company merges with another and you are out of a job, missing the watery coffee you’d drink with a side of gossip in the office cafeteria. Or you divorce and lose everything that was life, even those friends you thought you’d grow old with. Sometimes, tired of choking in your sleep, you do it: uproot yourself, pack up, and go where you don’t (yet) belong. But nobody stays a stranger to their surroundings forever. Here are 7 books about uprootedness:

Infinite Country by Patricia Engel

Infinite Country is a love poem to the bravery of choosing uncertainty, of choosing the possibility of life even when chasing it might also bring death. Engel writes the brisk, humorous, heartbreaking mutigenerational saga of a Colombian American family learning the role of love when all—family, land, home, and even country—is threatened.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous follows an immigrant Vietnamese boy who grows up loving the monster that life and his own culture made of his mother; the most important person in his world. To survive he will write a long letter, through it, rebirthing himself by unflinchingly rescuing the pieces of himself.

We, the Animals by Justin Torres

We, the Animals is also a coming out and coming of age story with an immigrant family at its center, but here what threatens to uproot is family. It’s a home so infested with the culture of toxic masculinity that it kills its own. Yes, you will cry a little, curse a lot, but the way in which the narrator emerges from it all, will have you reading and rereading it for years to come.

Ordinary Girls by Jaquira Díaz

Ordinary Girls is a fantastic memoir of second chances for those uprooted again and again. The uprooting agents here are drugs, mental illness, racism, poverty and Puerto Rican colonization. Read to find out how this girl so many times left for dead in glamorous glitzy Miami Beach, lives to love and forgive. Her story is for anyone who has moved so much and done so much that they are ashamed and doubt they will ever be home in themselves again. After you read it, you will know without a doubt that we are all snails, carrying home with us wherever we go.

Floaters by Martin Espada

Floaters is a sketchpad of Latino immigrants whose lives the author witnessed through his father, a civil rights and community activist, and a talented photographer. Espada himself creates word pictures in the form of prose poems here, or rather word films, his clear gaze and empathy for the sacrifices of people forced to live between borders, as a subset of the country they’ve brought all their hopes to, is as inspiring as any daily prayer.

Women Talking by Miriam Toews

In the novel, a group of women violently betrayed by the men who were supposed to love them must choose a new way to be women in a world of men. Inspired in the real life case of the “ghost rapes” that occurred within a remote Mennonite community in Bolivia in the mid-2000s, it is uprootedness at its most gripping, written as if transcripted from a trial. I remember reading it with baited breath; Toews’ dialogue is better and more suspenseful than the most popular of crime thrillers. The gift of it? It left me feeling more rooted for reading it; more strongly belonging, claimed by the global country of women.

The Twilight Zone by Nona Fernández

The problem with revolutions is that some people will lose their country, and sometimes that will be you. In this masterpiece of an I-novel, the unnamed protagonist—a woman much like author Fernández—has grown up uprooted by the trauma of the dictatorship that throttled her country for decades. Now working on a documentary about the torturers of Pinochet’s government, she writes to the one who populated her nightmares. In gathering his story, and confronting it with her own memory of events, she will come to a redefinition of the executioner, finally face the collective guilt displacing her from her own country.