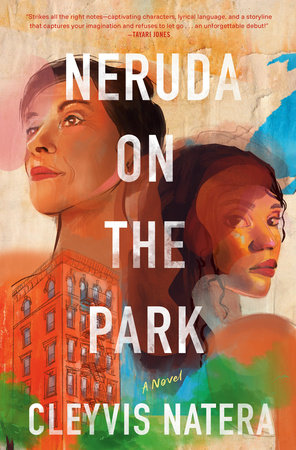

Gentrification takes center stage in Cleyvis Natera’s debut novel Neruda on the Park, which follows the different reactions the members of the Guerrero family have to the impending redevelopment of their predominantly Dominican New York City neighborhood.When a neighboring tenement is demolished to make way for a luxury complex of condominiums in their neighborhood, the mother, Eusebia, begins devising a dangerous plan to prevent the complex’s construction, oblivious that her daughter, Luz, a rising associate at a top Manhattan law firm, is falling for the handsome white developer.

In Neruda on the Park, author Cleyvis Natera creates an intricate portrait of a close-knit community in crisis, exploring how gentrification impacts communities and individuals, the nuances of ambition, as well as what it means to be a woman in an ever-changing world.

Natera immigrated to the United States from the Dominican Republic at the age of ten. She has won awards and fellowships from PEN America, the Bread Loaf Writers Conference, the Kenyon Review Summer Writers Workshop, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, which is where we first met.

Recently Natera and I discussed how she used Neruda on the Park to explore the violence inherent to gentrification, inter-community resentment, and what she learned from working on the same book for more than a decade.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: In the opening chapter, the main character, Luz, sees signs of impending development in her neighborhood and knows how it plays out—neon colored storefronts replaced with “yoga, juice bars, endless mimosa brunch places with lines out the front door.” Her apathetic response to the inevitability of gentrification is in marked contrast to her mother Eusebia, who goes to great lengths to protect their historically Dominican neighborhood. Can you discuss exploring gentrification and inequity in Neruda on the Park?

Growing up in New York City in the late 1990s, it was terrifying to realize how quickly people are displaced by the forces of capitalism and whiteness.

Cleyvis Natera: In Neruda on the Park, we’re introduced to Nothar Park, a predominantly Dominican and immigrant community in northern New York City on the cusp of great change. The gentrification that has violently altered neighborhoods all around New York has somehow missed this community and when it arrives, we see, as you mentioned, how starkly differently my two main characters react. While Luz, a young upwardly mobile lawyer, sees it as inevitable, her mother Eusebia, sees an opportunity to stand up and fight. The roots of this interrogation began from my own lived experience.

Growing up in New York City in the late 1990s, primarily in Harlem and Washington Heights where my family still lives, it was terrifying to realize how quickly people are displaced by the forces of capitalism and whiteness. It was critically important to me to bring the fear and rage that I witnessed during the times of most change in my own neighborhood to my fictional story. Gentrification is a force of erasure and of displacement and those who are most affected are often those who already occupy the most vulnerable places in societies across the globe. I’m a big fan of books that have come out in recent years that touch on this topic. But time and time again the change was taken as a given—as an impossibility. I wanted to explore the possibility of resistance. What if there was a community that refused to give in?

DS: Luz grows up in a tightly knit community but as an adult feels alienated from community members, who she feels are suspicious of her for going to college and then law school. Can you discuss writing about resentment toward success in communities which historically have been marginalized? Have you felt similar hostility upon publication of this book?

CN: There is a great deal of tension that lies in the intersection of the pursuit of the American dream and the realities of what it costs to attain it. So often, within the context of our society and especially within marginalized communities, success is defined and measured by material possessions—the more, grander, bigger and more expensive our lives appear from the outside, the more worthy of admiration we are. Our very self worth is positioned relative to what we have to show for our hard work and it is our possessions that are often poised as the surest path to happiness and self-fulfillment. When we meet Luz, one of my main characters, she has fallen in line with this philosophy of life. But she has a nagging, persistent feeling it may be a lie. I also wanted to show how difficult it is to exist within a community where there are equal parts admiration and resentment for “making it” and use that as a vehicle for Luz’s character growth and transformation.

I haven’t experienced any outright hostility upon the publication of my novel. Sure, some people I anticipated would come to the forefront to champion my book and help me celebrate it have not but the overwhelming reception to my novel’s splashy success has been met with love and support from those who matter most to me. I would just say, for the record, that after attempting to jump start a writing career for 15 years, I learned very early to keep my expectations low. It’s one of the best aspects of having made it so far behind many of my peers… Many have told me the support won’t necessarily come from people in our lives. Sadly, writers aren’t magicians so we can’t turn, even people who love us, into readers if they could care less about books. That’s why I am incredibly humbled when people I know as well as perfect strangers show up for me. The times we’re living through often make me want to run and hide and I don’t blame anyone for turning the world off for their own self-preservation. Do what you gotta do, people!

DS: Neruda on the Park explores the nuances of women’s ambition, particularly the pitfalls faced by high-achieving Black and Brown women. Can you elaborate?

I wanted to explore the complications of ambition through the lens of womanhood, especially when that pursuit acts in service of the same systems that keep our communities marginalized.

CN: I find current and past feminist/womanist movements fascinating in how obvious it is that so much of what stands in the path of true solidarity and lasting advancement for women are the same factors—intersecting challenges—that get in the way of our society moving toward a fairer and more just place. In my novel, I wanted to explore the complications of ambition through the lens of womanhood and hopefully create space for dialogue around the costs to our own bodies at constantly hustling to achieve, to break ceilings, especially when that pursuit acts in service of the same systems that keep our communities marginalized.

DS: In Neruda, you explore the way women’s bodies are perceived, by other women, by men, in different communities. Why is it important to write about this?

CN: During the time it took me to write and publish this novel, the culture has shifted drastically around women’s bodywork and cosmetic surgery. Walk around most major cities— notably Los Angeles, Chicago, New York City, Miami— and you’d be hard pressed not to be knocked around by augmented female bodies every which way you turn. When Luz and her mother Eusebia are discussing where they each stand as far as Eusebia’s sister, Cuca, pursuit a full-body makeover (in order to still her husband’s the wandering eye), I also wanted to give room the complexity of the bind we find ourselves in as women. “We cannot win,” Luz says to her mother— voicing frustration that women are expected to conform to certain standards of beauty but then are criticized when they go to cosmetic surgery for not being “natural.”

My main preoccupation with the persistent way in which women’s self-esteem is intentionally capsized in pursuit of a billion-dollar industry is how it metamorphoses. It grows more surreal year by year but never ceases to be centered on distraction. Who wins when we are constantly attempting to attain impossible beauty? What might happen if we ceased to be distracted by what our bodies should look like?

DS: In Neruda, you explore the blinders of the 1% regarding sustainability. For instance, one of the central characters is a vegan due to ethical reasons but also has a private plane. Why is it necessary to explore such contradictions?

CN: I’m often struck by how harm is done within and outside marginalized communities by people who genuinely believe their actions are in service of those same communities. In Neruda on the Park, I wanted the concept of villains or antagonists not be flattened—to provide plenty of room within a context that can be seen as humorous in its absurdity. I find it is sometimes easier to speak of difficult, weighty subjects when fiction eases the way by showing how truly incomprehensible we are as people. How often do we do the opposite of what we stand for because it is easier, or because we’ve never been forced to consider the ramifications due to our privileged place in society?

DS: It took you 15 years to write Neruda on the Park. Can you discuss remaining committed to a project for that long?

CN: You know, it’s crazy to say this but because Neruda on the Park came at the heels of a failed book— my MFA thesis novel which I never sold—I told myself very early on that it was publication or bust. For better or worse, I wouldn’t move on to another book until I published it. I stuck to the stubborn belief that this was the book worth digging my heels in about. I also feared that if I abandoned yet another project, I would never learn the lessons inherent in taking a seed born in the imagination and turning it into a book others can hold in their hands, perhaps be moved in a meaningful way by it.

Since the book was published, I’ve been asking myself whether I might have been better off if I would have moved on to another project at some point and the truth is part of the reason it took so long is because I did—I stopped writing altogether during periods of my life for many reasons. Where I’ve landed now is that I’m grateful this story haunted me, forced me to become a better writer, helped me live a life that informed me as a human so I could rise to a level worthy of being its creator. There are several sentences in this book that survived so many revisions and edits, and when I find them, it ignites within me such tenderness for what this story and I have been through. It fills me with gratitude and, I can’t lie, a little sadness that we’ve now arrived at a point where the story will have a relationship in the world independent of me.