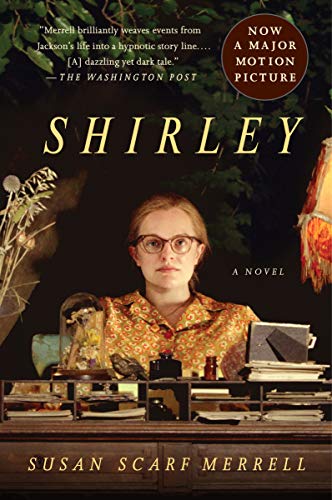

Susan Scarf Merrell is the author of Shirley: A Novel, which has just been adapted into the new film Shirley, written by Sarah Gubbins and directed by Josephine Decker. The film stars Elisabeth Moss as Shirley Jackson and Michael Stuhlbarg as her husband, Stanley Hyman, each delivering unforgettable performances. Aided by the rich research and lyricism of the original novel, which runs skeletally throughout the story, the movie is a sharp, creepy delight—whether you are a Shirley Jackson fan (yet) or not.

The film released on June 5th, and is available to rent and buy on platforms like iTunes, Amazon Prime, and Hulu. Select drive-in theaters are also showing the movie, according to the film’s producers at Neon.

Both Merrell’s novel and the film bring to life the Vermont home of Shirley Jackson and Stanley Hyman. The stories are told through the eyes of the young Rose Nemser, whose husband, Fred, is joining the faculty at Bennington College. Rose’s fascination with Shirley Jackson grows ever more complicated as the two women forge a dynamic and nerve-racking friendship. The novel takes place in 1964, as Jackson begins work on her final, unfinished novel Come Along With Me, which I had written about previously for Electric Literature.

I spoke to Merrell about her book, the new film, and why she thinks Jackson’s work is striking such a powerful chord with today’s readers: psychologically deft, deliciously perverse, filled with weird, surreal magic that makes us questions all our assumptions about reality—or whatever of those we have left, these days.

Merrell also co-directs the Southampton Writers Conference, and is program director of the novel incubator program, BookEnds. She teaches in the MFA in Creative Writing & Literature at Stony Brook Southampton.

KJ: So, thanks so much for talking with me about Shirley. It was fascinating to read your novel after seeing the movie. They’re both so beautiful, and also very different.

SSM: So very different but, at least to me, very much on this sort of continuum, beautifully honoring where Shirley came from and her interest in folklore and mythology and the way that she was always really turning to material from our literary history.

I fell in love with her and had this response to her work, and then [screenwriter] Sarah [Gubbins] had the same thing happen, and [director] Josephine [Decker] even more, and the actors… it feels very much as if the imagining, and reimagining, and reinterpreting, all has this beautiful lineage. It feels kind of perfect to me.

KJ: If I can back up a step, how did you first find your love for Shirley Jackson?

SSM: I had written two books, and I was sort of at a stalled place. I really didn’t know what I wanted to do, and I decided to go to graduate school. And because I had small children at home, I ended up at the Bennington Writing Seminars, which is a low-res program.

I went home and started reading Jackson and by the end of the semester I had read absolutely everything she had ever written.

On the first day that I was there, I was talking to my instructor for the semester and she said, “Well, what do you think you want to do?” and I said, “Well, I’m really interested in domestic stories but kind of magic… that’s really where my heart is,” and she said, “Well, have you ever read Shirley Jackson?” and I said, “I think when I was a teenager I read We Have Always Lived in the Castle. I should go back and look at it.” And I went home at the end of the residency and I started reading Jackson and by the end of the semester I had read absolutely everything she had ever written.

The next semester, I went back and I had a new instructor and he said, “So, what did you do last semester?” and I said, “I became obsessed with Shirley Jackson,” and he said, “Well did you know that she lived here for her entire adult life?” and I felt like I had almost been punched, it was so powerful.

During the course of that week, I realized that I have been walking past her house every day, that I had been buying coffee at Powers Market, where she got the idea for “The Lottery.” I had really been in all the places that she had been. I had been soaking her up without realizing it. When I went home that semester, I went down to the Library of Congress and spent a couple of days going through all of those papers. I just knew I wanted to do something with her, but I didn’t know what.

In the beginning, I started writing these little monologue-y things that were in some voice like hers, but I could never really be her. And then I thought, “Oh, maybe I’ll write a biography of her,” and I went out to California and I met Lawrence, the oldest son, and he said, “You know there’s already somebody who’s writing a biography. A woman named Ruth Franklin. You know, but you could do it too.” And then I met Ruth and I thought, “This is crazy. This is not really what I should be doing.”

In any case, I started writing a “looking for Shirley Jackson in my own life kind of thing” and that wasn’t it… this is now years and years.

And one day I was walking in the woods near my house with a writer friend of mine and I said, “I just don’t know. What if somebody went to visit Shirley and Stanley, and I could tell the story from that point of view?” and it just was like everything clicked.

I think my obsession started in 2007 and this was probably 2010, maybe even maybe even later.

And I knew exactly who Rose was from the get-go. I just knew everything about her. She just came to me and so that was it. And from that point the story just flew out. I knew so much about them. And I knew what I wanted to say but I finally had found the way.

KJ: Yeah, I was going to ask. I sort of assumed Rose was a fictional character, but I wasn’t sure if maybe she was based on somebody real from Shirley’s life, or if she was your own way into the story.

SSM: Somewhere in the journals, which are pretty sparse, there is a country that says, “c. came to stay.” And, and that was kind of it. And then I called my mother that same day and I said to my mom, “I want to base a character on you and your life,” and she had grown up very poor in Philadelphia. And she said, “Oh, you could do whatever you want! Don’t worry!” And there’s maybe three words, because she gave me that permission. Not one vowel more than three words are about my mother’s childhood, which was that she grew up in a very poor family, but just getting that permission was somehow was grease—and then Rose just came alive as her own person.

KJ: It’s a beautiful way into the story and I found myself as fascinated by Rose as I was by Shirley.

SSM: I think for me, one of the things that was always very important was that Rose’s viewpoint, as Rose herself got crazier, had to be the viewpoint—because I knew I was imagining a story about real people.

I love what the filmmakers did with that obsessional connection. It was an extraordinary interpretation of all the valences of love.

One of the things I really love in the movie is that the question of whose mental health is more at risk is very clear, and maybe more ambiguous than in the way that I saw it. Because I really saw Rose’s need for the connection with Shirley and Rose’s need to have a maternal figure… you know that was really the driving force. Her competition to be the best child. And I love what the filmmakers did with that obsessional connection. It wasn’t the way my brain went, but it was just this extraordinary interpretation of all the valences of love.

KJ: In your novel, Rose comes to see Shirley in 1964, which is just a year before her death, when she was writing her unfinished novel, Come Along With Me. (The movie takes place earlier.) What drew you to that year late in her life? Was it the unfinished novel?

SSM: So, I was stuck on two things: the agoraphobia which was so much worse in those years right after The Haunting of Hill House and that are sort of manifested in Castle. And so, I was stuck in that time period the whole project. And the idea that Sarah looked at the cinematic logic and decided to connect Paula Weldon, Hangsaman, and that time period was just—I just thought it was so brilliant because within the constraints of film, it just had to be that way. But I was always locked into the agoraphobia and the writing of the last novel.

KJ: It’s fascinating. Shirley was going through all of that, but in Come Along With Me, the protagonist, Angela Motorman is so free—her husband has died and she’s let loose on the world.

SSM: You know, I think Ruth has this in her book. It’s quite powerful when you look in the journal notes. Among the many things that she’s typed on one piece of paper is, “writing is the way out writing is the way out writing is the way out” and no punctuation. And you just know that for this person, that was it. This was the only way to come back to life.

KJ: Another really wonderful part of both your novel and the movie is the treatment of the complex layers of her marriage to Stanley Hyman and how they worked off each other, intellectually and romantically, and I was curious how you came to understand that relationship while working on the novel?

SSM: Way before I had even the slightest idea of how the book would manifest, I gave a lecture, as part of my graduation at Bennington about Shirley and her work and her life. And Susan Cheever asked from the audience, “Do you think it would have been better if they hadn’t met?” And the big question was always what kind of life would they have had without each other? And would it possibly have been better to not have made this work, and to not have had what I think was such an incredibly supportive intellectual connection? All the other shit, you know, notwithstanding.

Their brains were connected as if they had wires between them and so, you know, that’s one of those questions that I think only an ethicist could answer.

For me, without that connection between them, I’m not sure that either of them would have become the great artists that they became. I mean Stanley also was just a brilliant writer. He has this one book on all the different ways that you can interpret Iago… different literary theories and the book is just mind-blowing. The guy is so smart, and they were just feeding off each other, back and forth. So, I mean, selfishly, I am very glad they had this life together.

KJ: Is Shirley Jackson coming into some kind of moment? In the last few years we’ve seen more film adaptations, and there’s a Netflix version of The Haunting of Hill House… why now are people discovering and reconnecting with her work after all these years?

SSM: There are two things. The reason that writers connect with her work is that it’s extremely tautly structured, and when you start pulling her stories or the novels apart, you see that the work is so consciously made that there’s a lot to take from it artistically. It has a look of a spontaneity and it’s not spontaneous at all.

And then the other thing that has to do not just with writers, but also with readers, is that she really was able to capture a way that we need to laugh at the darkest places in ourselves in order to make sense of them.

There’s this kind of humor underlying everything, that is a relief and a release, but she’s also really acknowledging—both with the magical stuff and with the non-magical stuff—she’s really acknowledging the truth of living inside of one’s head. Sometimes you hear a voice, or sometimes you imagine there’s something under the bed, but you’re still a regular person who has to get up and get dressed every day. She hits both the reality and the imaginative richness of regular life.

And then I also think she understands something about women that women know, which is that no matter how domestic a woman’s life is, there is this role and place where imagination and the creative soul are always present. And I’m not at all saying that men don’t do this as well, but I think it’s a kind of a secret of being a woman that she tapped into at a pretty early time. She was saying, “Oh yes you can do this.”

I think she really resonates for people who are striving to be both normal and not normal at the same time.

There’s a scene in the book where they’re talking about Betty Freidan, and she had really tapped into that idea, in the same way that Phyllis Schlafly had a really big job, being a person who said, “Stay home,” Shirley Jackson had a really big job, saying, “Hey, I get you. I get what it’s like. I can do it; you can do it. You can do both these things.”

And the part of her that told everyone that she was a witch, I sort of buy it. I mean, part of it was just that they were so immersed in all of this folklore and mythology and stuff, but there was a way in which she had some ability to sort of see, and maybe imagine her future. I think she really resonates so much for people who are striving to be both normal and not normal at the same time.

It’s wonderful to me that she would be having a day, or a decade or more would be quite nice.

KJ: Yeah, I found myself finishing the movie hoping that a lot of people will be discovering her work, if they hadn’t before.

SSM: Somebody said to me the other day that they hope this movie sells the hell out of her backlist. You know, I wish everybody would read her. I wish everybody would read The Sundial right now, which is all about the end of the world and rich people and poor people and regular people and all of the issues. She just was tapped into everything, you know?