Clarice debuts on CBS All Access today, promising a “deep dive into the untold personal story of FBI Agent Clarice Starling.” But what is the impact of consuming these shows that explore the minds of serial killers?

Not too long ago, Romantic poet Keats declared that “‘beauty is truth, truth beauty,’ – that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

But what happens when Beauty is separated from Truth, or worse, deliberately used to mislead, confuse, and disorder our mind, heart, and soul? So that instead of abiding by the laws of beauty to ennoble our thoughts, words, and deeds, what is beautiful is presented to us alongside what is ugly and wicked?

Speaking of false prophets, Sufi mystic poet Rumi put it this way:

Judging his words with taste-buds well refined

A few sensed sweet and bitter were combined:

He’d mixed the words of saints with those of cheats,

Like hiding poison in amongst the sweets,

He seemed to say, “Stand firm while on the way!”

But to their souls, “Be weak!” he’d really say

—The Masnavi, Book One

(Translated by Jawid Mojaddedi)

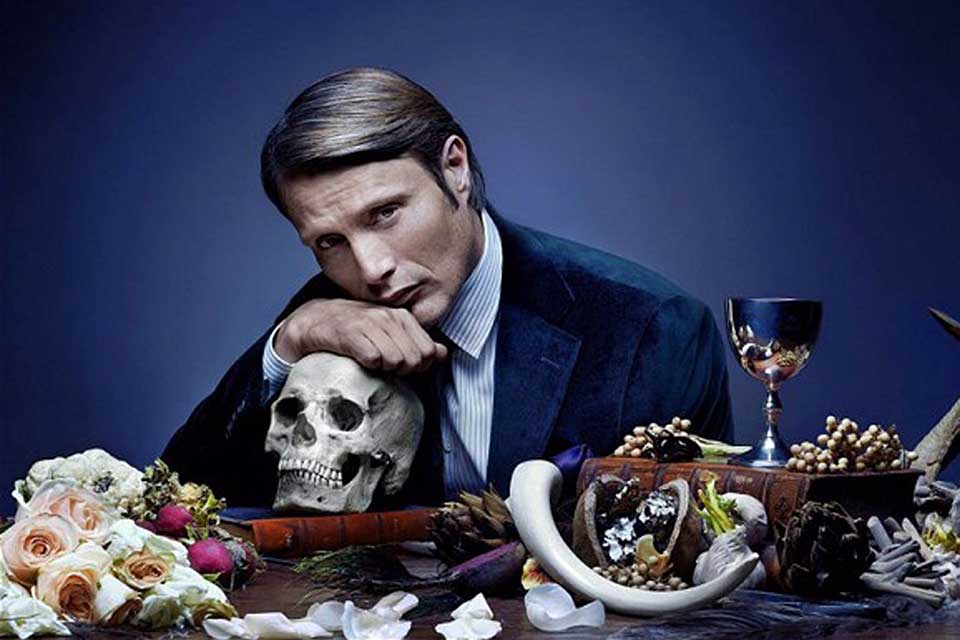

Something of this unholy mix is taking place in a series showing on Netflix based on a fictional homicidal cannibal, Dr. Hannibal Lecter, made famous by Anthony Hopkins in The Silence of the Lambs, adapted from Thomas Harris’s 1988 novel of the same name.

I admit, as a young man, I was susceptible to this dark thrill, compulsively reading Stephen King books and drawn to horror films. Despite ourselves, we are fascinated by the monstrous. To varying degrees, we are intrigued by the question of why certain people transgress the laws of man and G_d to take a human life. The psychopathology of murderers—serial killers, especially—seems to exert a particular fascination on us and is the subject of countless movies and documentaries regularly dropping on Netflix, exploring these twisted “geniuses.”

Hannibal, the series created by Bryan Fuller, is a contemporary example of such unedifying art—all beautiful surfaces, but little heart. Like its demented protagonist, Hannibal seems to be told from the perspective of the murderous psychologist. The series revels in beauty that is divorced from truth: exquisitely prepared meals, enchanting music, and scenes that ravish the senses: including elegant, clever conversation, even impeccable dress on the part of the bad doctor. But all this style cannot disguise the alarming substance that it delivers to us.

Nor does it try to. Fuller’s Hannibal is a love letter to perversity, glorifying violence and murder while romanticizing cannibalism. In a word, it is decadent, reflecting moral decay or cultural decline and reveling in it. Watching it, I am reminded of poet William Blake’s assessment of the author of Paradise Lost; Blake said Milton was of the devil’s brigade when he composed the epic poem, which glorifies Lucifer, without knowing it. Incidentally, Lucifer is also the title of what was officially named “the most-watched streaming show of 2019” and is now in its fifth season on Netflix. Makes one wonder, at times, what the hell is going on that has us so beholden to the diabolical?

At one point, in season 3, Hannibal is explicitly likened to Satan by the person who perhaps know him best, the intuitive and complex Will Graham, a criminal profiler who catches serial killers through his empathic ability to identify with them. Visiting a grand cathedral in Florence, in pursuit of Hannibal, Will makes this chilling observation: “Defying God, that’s his idea of a good time. There’s nothing he’d love more than to see this [church] roof collapse mid-Mass, choirs singing. . . . He would just love it, and he thinks God would love it, too.”

Presented with Oscar Wilde’s essays, Intentions, Franz Kafka said to Gustav Janouch in his Conversations: “It sparkles and seduces . . . And that is one of the book’s great dangers . . . because it plays with the truth. A game with truth is always a game with life.”[i]

Fuller’s Hannibal is such dangerous art that plays with truth, life, and beauty while exercising the seduction of (d)evil. Unconsciously or not, this series seeks to hypnotize its audience so that we might lose our moral compass (the way so many of Hannibal’s patients do) and root for its antihero.

As an illustration of its deep cynicism, bordering on nihilism, here’s a snatch of an exchange that shamelessly spells it out, between Hannibal and his psychiatrist/love interest (also at the opening of season 3).

“You no longer have ethical concerns, Hannibal. You have aesthetical ones,” she says.

“Ethics become aesthetics,” he replies. “Morality doesn’t exist,” he adds. “Only morale.”

This is neither clever nor witty. Art matters; it shapes our consciousness and conscience as well as having the power to inform our actions.

Further, in the rattled United States of today—where our physical and psychological condition has been upgraded to serious—we often speak of a mental health crisis in connection to gun violence, another widespread malady. Is sensationalist, gratuitous gore healthy company in the midst of a global pandemic and a second presidential impeachment, following a failed insurrection attempt?

Ultimately, we live in a moral universe, and whether we recognize it or not, amorality is akin to immorality. As consumers of depraved art, we are what we eat.

Washington, D.C.