Once at a party, I met an anesthesiologist. I’ve always been horrified and fascinated by anesthesiology, and I was a few wines in, so I cornered him.

“Where do we go?” I demanded. “When we go under, where do we go?”

He didn’t seem surprised to be accosted with this question. Instead, he moved closer to me. “Well, you are like a computer,” he said. He lifted an index finger and pressed it to the center of my forehead. “I’m just turning you OFF. I’m flipping a switch.”

I was furious. The answer was clever, but it meant nothing. It didn’t address my issue. It didn’t help me understand how he did what he did, or whether I was dying every time I went under.

Obviously, anesthesiology and writing are not the same. But novelists are also asked a similar question at every event, family gathering, therapy session, good date, or party: How did you write your novel? Over and over again. Writing a novel is wrapped in the same mystery, for most people, as going to the moon or going under anesthesia.

It’s not a question I can answer once or in one way—my relationship to writing changes as I get older, as I write more books. Some technical advice stays the same (i.e., the practices I cling to in order to finish the damn thing), but other, more existential questions fluctuate with time, my life experiences, and the political environment that encroaches on my existence. Still, here is my best crack at it: five easy steps for turning your suffering into a novel.

First You Must Suffer

It would help, for example, if your father has just died. Or, perhaps, you’ve just undergone an incredibly painful and traumatic spinal surgery. Both of my novels were directly fed by these two critical moments in life, times during which my understanding of the world around me was proven entirely wrong.

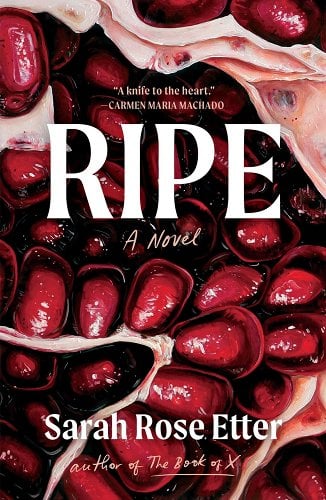

My new novel, Ripe, was written after my father died suddenly, an event that was followed shortly thereafter by the COVID-19 lockdown. My father was always telling me to write this novel—a novel about working in tech with lunatics. During the year I spent working in Silicon Valley, at the end of our phone calls, he would often say: Take notes on everything that is happening to you. One day you’re going to write a book about it and sell a million copies.

After he died, during lockdown, I was entirely alone with my grief. There was no looking away from it, there were no distractions, it was only me and the grief, which was six-foot-three, the height of my father, following me around, getting in my way, forcing guttural cries out of my body at all times of day. After a few weeks, I sat down and wrote the book he asked me to write. Ripe, even more so than my first novel, was born of grief and isolation, made in a moment in time that I’m not sure will ever happen again. But it was fuel inside of me, an agony I wanted to comprehend, make sense of, catalyze into something else, something useful, something he would be proud of.

Perhaps for some writers, like romance novelists, “Suffer” can be exchanged for “Fall in Love.” If you can write a novel without suffering, my hat is off to you. For me, the work is deeply driven by a desperation to understand the world around me.

Be Ruthless, Be Rude

We are raised (at least, I was) to be polite, kind, presentable. Often, the writing we want to do is the opposite. To write a great novel, you must be ruthless—ruthlessly honest about the people around you, the characters in your book, your perception of the world, your family, your coworkers, and, most of all, yourself.

Humanity is shown clearest in its ugliness. A character that is behaving terribly becomes suddenly understandable when you realize she is trying to have a child but cannot conceive. A depressed character might seem annoying on page one, until you realize she is pregnant and impoverished.

The writer Vidjis Hjorth has an excellent bit about this in one of her novels. Her character, who has herself just written a novel, is asked if the novel is real. The character responds that she is not interested in reality, but in the truth.

That distinction is an important way of securing freedom from the confines of what’s expected of us in our work. We have to be unconcerned about whether reality is reflected in the novel, and dedicated to ensuring our work is dealing in the sometimes beautiful, sometimes ugly truth of being human.

Outline, Outline, Outline

I believe strongly in two things at this stage in my career: plot and outlines. Early on, when I was young and stupid, I believed the artistic impulse that shot down from the heavens and into my body was all I needed. At the time, it felt true because when I was overtaken by that impulse, I would often write whole-cloth first drafts that only needed minor polishing. It felt like a higher power was driving the work. And that was beautiful. I thought that was the only way it was done.

As I got older, I realized that those flashes of brilliance cannot and will not sustain a career. Throughout my life as an artist, I’ve always had a full-time job. Almost all of my drafts have been written on nights and weekends, or during two-week vacations from work when I holed up in a cheap condo somewhere and wrote like an unshowered demented demon in yoga pants.

My point here is that my time for writing is limited. I do not have time to burn on work that I will ultimately throw out. Of course, during the editing process, pages will be cut and re-shaped, but I cannot make huge mistakes that will require gigantic rewrites—not without tanking both of my careers or spending the rest of my life on a book that will never see the light of day.

So, I have to plot. I’m experimental by nature; at first, I resisted plotting and thought I could just wing it. But the reality is, since the literal dawn of mankind, humans have been drawn to plot. From cave drawings to the Bible, we’ve been hungry for a story where something happens. The most basic plot structures are successful because they entertain their audiences.

Whenever I set out to write a novel, I grab a basic plot structure and mess with it a little bit. I love a good plot remix. I often point to “Parasite” as a great example of a movie that took a traditional plot structure and then put one part of it—the Rising Action—on steroids. Most of the movie is just an exercise in raising the stakes higher and higher and higher until the tension is near unbearable for the audience. And then the movie resolves.

I break each part of my outline down into specific scenes. This is important for me because if I had to figure out what I was writing every day that I sat down to write, I would lose my mind. Instead, once I’ve distilled the outline into scenes, I put each scene on an index card and add some details on the back.

At the end of all of this, I have a giant stack of index cards. Each day, I sit down and pull a card. That’s the scene I write for the day, and typically that gets me to between 1,000 and 3,000 words. The method works for me because my task is crystal clear, and focusing on individual scenes drives me to both compress them and make sure they end with a gut punch. (If you want more technical advice here, I write the scenes individually in Scrivener so I can move them around in their respective sections as needed. Scrivener gives me the flexibility to change things without an entire rewrite, especially between the first and second drafts.)

Let the Baby Be Ugly

Another reason people give me for being unable to finish their novels is that their first drafts suck. Well surprise! All of our first drafts suck.

When a baby is born, it comes out disgusting. It’s hideous, something right out of a nightmare: bloody, screaming, covered in goo and attached to its mother by a hideous cord. If it looked that way forever, I believe most of us would stop having children. But then the nurses take the baby away and get rid of the blood and put it in that white cloth, which suggests it is an angel and everyone coos (even if the baby actually remains very ugly).

My point is this: Your first draft is the ugly, bloody, screaming baby attached to you by a disgusting cord. And you’re sitting there, all torn up and crying and on drugs, waiting to come back to a reality in which the baby isn’t an ugly, bloody, screaming mess.

Your job, therefore, is to get the first draft out as quickly as possible—for a few reasons. The first is that while you are writing your first draft, your brain is opening up in a way that will not last forever. I had a friend who once told me that whenever you write a novel, a portal opens in your brain and once you get the first draft out, the portal closes and you can never get back to that place again. That’s been true in my experience—I fundamentally believe it is impossible to write the same book twice because I could never get back to where I was mentally when I wrote The Book of X and Ripe.

So getting the first draft out is like capturing lightning. During the first draft, I write almost every day. It typically takes one month if I’m not working my other job, and six months if I am working my other job. Here is where the discipline comes in: I write for one hour at night after work every day, and from nine to five on Saturday and Sunday, no exceptions. There is no special secret or trick here. There is only dedicating your time to your work and giving yourself permission to make an ugly first draft.

Too often, I hear writers asking about which publisher they should get or what their cover should look like when they don’t even have a first draft. And I always say this: If you don’t have a first draft, you don’t have shit. An idea for a novel without a first draft is just vaporware.

Edit Until Your Fingers Fall Off

The bulk of my work is in editing, or what I call “wiping the blood off of the ugly baby.” The reason it is so important to vomit up the first draft, no matter how bad it is, is that you can fix almost anything after it’s written. With a bad first draft, at least you have something to edit, refine, fix. With no first draft, you’re just a guy in a bar telling a woman about the book you almost wrote once. Sad.

Most of my first drafts take a few months to get down on paper. But the editing takes years. For both novels, I spent between three and five years editing them constantly, either by myself or with an agent, editor, or publisher. This part requires a totally different type of endurance from writing the first draft. It’s more mathematical, more methodical, more technical. Editing is another way of asking the question: How many times can you stare at the same page before you fire your friend/editor/agent/publisher? And the answer is: a shit-ton.

When you get worn down, when you want to give up, I’ve found it helpful to ask myself whether my favorite author would have stopped now. That’s usually enough to get me back at it—it’s hard to keep moping when you know Joan Didion and Sylvia Plath and Deborah Levy and Diane Williams kept going until it was right. It reminds you that this is part of the gauntlet.

And it is a gauntlet. The process of coming up with an idea and turning it into a first draft requires one type of endurance. The process of editing that work requires an entirely different type of endurance. And when it’s time for your novel to be sold and published . . . well, that’s a different essay. You’d have to ask that question at a different party altogether, because I don’t have the patience to answer both at once.

Writing a novel is impossible. I never thought I would do it. It is tantamount to building and solving a puzzle by yourself. It’s endlessly fascinating and humbling. It’s a process I will never master and that’s why I love it. If I’m lucky, I’ll have written five or six books by the time I’m dead. If I’m extremely lucky, two or three of those will be decent.

Maybe, like the anesthesiologist, my answers here aren’t good enough or clear enough. Maybe my thoughts here don’t entirely solve the mystery of writing. Maybe, when you ask me this annoying question at a party, I should lean over and tap your forehead: “Your brain is a computer. Just turn it on.”