When I was in my early twenties I watched the movie “Annabelle” with my cousins and brother. It did its job in discomforting me, but I’ll never forget what my brother said as he watched, bored, eating popcorn, and checking his phone. “After all our ancestors went through, there is no way they’re just going to sit by and watch us get tortured by some white ghosts.” We all laughed and endorsed his sentiment and while I still had a little trouble sleeping that night, I do think I slept easier with my brother’s words on my mind.

Most of what we consider classic horror was created by white men.

Horror, as a genre, has always fascinated me. As a child I watched the screen adaptation of Stephen King’s IT and wondered why someone had to go so far outside of reality to make something that was considered scary. Why invent an evil clown when there are plenty of real life clowns making decisions about legislation and running corporations that bleed the earth dry? We don’t even have to think that broadly: Have you ever been the only Black girl at a pool party and gotten your hair wet? Are you a woman walking alone to your car at night? Have you ever been Black or Brown and pulled over by the cops? That’s all horror, too.

Are you a woman walking alone to your car at night? Have you ever been Black or Brown and pulled over by the cops? That’s all horror, too.

Most of what we consider classic horror was created by white men. The genre, both in film and in literature, is plagued by the same white male gatekeeping that most entertainment disciplines are subject to. Algernon Blackwood, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, W.W. Jacobs, and Edgar Allan Poe all had a part in shaping how we understand classic horror today. The creation of supernatural forests, beings, objects, and obsessions sets a precedent for horror to focus on the invention versus observation. Part of horror’s beauty is its responsibility to invent and create. Where would we be without characters like Frankenstein, Pennywise, or even Chucky? They are beloved, and important. However, the tragic outcome of this gatekeeping for horror, as a genre, is that it’s given us finite access to a limited imagination when it comes to source material. White male writers’ ability to explore the monster in themselves is stunted, at best. I’m not anti-invention, I’m anti-invention without accountability. The aforementioned writers wrote groundbreaking work in so many ways, but the centering of whiteness has never been groundbreaking.

The years surrounding Blackwood’s The Willows were ripe with tense race riots. Le Fanu’s Carmilla came out the same year as the bloody Colfax Massacre. Jacob’s The Monkey’s Paw came out at the same time as the Filipino War, and Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart was published the same year as the 1843 Cuban Slave Revolts. I am not of the expectation that white men would be able to write anything insightful about the horrific current events that existed during their lives. White people have demonstrated over and over again that while the systematic prejudices white supremacy has created might be embarrassing to them, if they are even aware of them at all, as far as they are concerned they don’t qualify as horror. I am of the expectation that non-white folks, LGBTQIA folks, disabled folks need to write it themselves. And this is not to erase any previous brilliance a white man may have happened to create, but to stand beside it. Racism is a horror and should be explored as such. White folks have made it clear that they don’t think that’s true. Someone else needs to tell the story.

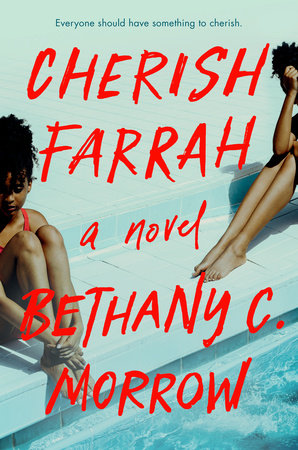

Usher in the needed present era of social horror. Bethany C. Morrow’s new novel, Cherish Farrah is a slow burn social horror that explores race from a multitude of angles: how white liberalism—despite its performative commitment to “the work”—continues to perpetuate dangerous and harmful ideologies rooted in classism and white supremacy, the ills and complicated legacy of transracial adoptions, and the barriers to social mobility for Black families, even those who do everything right.

The story follows two teenage Black girls, Cherish Whitman and Farrah Turner. Cherish Whitman is the product of a transracial adoption: she is Black and both of her parents are white. Blue-blood white, the kind of white that acquired its wealth, at least in part, off the oppression and disenfranchisement of Black people. There are family heirlooms, different houses for different occasions, relationships with powerful and influential people, like judges, that go back decades. Despite this truth, Cherish’s parents are deeply committed to her. Upon finding out that she was going to have a Black daughter, Cherish’s mother, Brianne Whitman, was “… of course … mindful enough to take a class. Not just in Black American studies, either. On hair care, on skin and makeup, too. She wasn’t going to bring home a baby who looked nothing like her and act like her love was enough. That’s not who the Whitmans are.”

Throughout the story we are repeatedly posed with the same question: can the Whitman family work to dismantle systemic injustices while also benefiting off of it? Morrow gives us a conclusion of sorts and the extent to which it will surprise the reader will likely be in direct correlation to their understanding of racism in this country.

White liberalism continues to perpetuate dangerous and harmful ideologies rooted in classism and white supremacy.

Cherish’s relationship with her parents is where the novel explores the power dynamics inherent in transracial adoption. They spoil her to the point of oblivion. Cherish, for all intents and purposes, functions at the same naive and privileged level as her white peers—this point is driven home by Farrah’s nickname for Cherish, “white girl spoiled.” When it comes to the subject of Cherish’s race and the sobering realities that accompany being a young Black woman in America, the Whitmans take the approach that many liberal white people take—they treat systemic racism as a thought experiment. There’s little, if any recognition of racism as a real lived experience that every Black person, including their privileged daughter, must navigate. Their tactics are bizarre and harmful and ultimately end up being their demise. Cherish, the one they want to protect the most, suffers greatly because of it.

Farrah’s horrors, in part because she comes from a traditional Black family, are another reflection of the systemic racism that BIPOC folks are used to. After being hit by financial hardships the Turner family is forced to abandon the cushy lifestyle they were hardly able to afford in the first place. Farrah gets a rude awakening when she asks her parents if they can just “move a few things around for awhile,” meaning money, the same way she saw her classmates’ parents do when they seemingly lost everything. She says: “One year, someone’s family ‘lost everything’—but everything didn’t include houses or boats or memberships. Everything was a feeling, a state of being … how was I to know it wasn’t the same for us?”

The Whitmans take the approach that many liberal white people take—they treat systemic racism as a thought experiment.

When Farrah is invited to stay as a guest at the Whitmans’ house, her obsession with appearances and control clouds her ability to see reality. She thinks she can manipulate the situation, and position herself to take a place beside Cherish on a matching white girl spoiled throne. Her need for control drives her to do some pretty gruesome things, including assault and battery, biting someone’s tongue off, and driving a nail through her foot. There are many times throughout the story where the reader may find themself trying to figure out who is the victim, and who is the victimizer, but it is repeatedly clarified that despite how much power and control Farrah thinks she has, or tries to exhibit, it is nothing compared to the system—represented by the Whitmans—she is up against. The unrest she experiences at the hands of the Whitmans is imaginative and fanciful, but the isolation and self-denial that came with it is an all too real and accurate portrayal of everyday life under white supremacy.

When I was in middle school I was a member of a performing troupe. At any given time I was the only Black person out of forty kids. Everyone else was white. While the public-facing persona told a family story—that we all lovingly worked closely together to ensure that our performances went off without a hitch—that wasn’t always true beyond the facade. There were your standard early-2000s aggressions: asking if my skin got darker in the sun, or if the ponytail piece my mom purchased to make show hair easier was actually my real hair, or even the director of the troupe once telling me—completely out of the blue—that he was part Cherokee. But there were also outright moments of torture: one member calling me a nigger over AIM, and other members’ younger siblings refusing to play with mine because he was Black. Seemingly unprovoked, shortly before I quit, I cried and cried in the dressing room— almost missing my cue. All of my cast mates felt deeply for me: we hated to see each other upset, but they were also confused. They couldn’t possibly comprehend that they were the source of my anguish.

I loved being in that group. It was my introduction to theater and musicals, things I continue to have a relationship with to this day. It was the first time in my life I had permission to pursue something picked by me, as opposed to my parents, and I took it seriously. I practiced dance moves even after rehearsal was done. Oftentimes rehearsing in my basement was the last thing I did before I went to bed. I was good. I was one of the strongest singers. Though I was only twelve, I was often cast in the more advanced numbers with the seventeen and eighteen year olds. This is how I exhibited control. This is how I thought I would secure my throne. But alas, one Black girl’s determination will never be bigger than white supremacy.

My parents, like many Black boomers, had a healthy amount of faith in respectability politics, a mindset I imagine Farrah Turner’s parents might carry as well. Why else would they put their child in such a white environment? My parents went to great lengths to ensure that my siblings and I were distinguishable from the other Black kids in our school district, in part by their achievements. They hoped their exceptionalism would protect us. My mother was the first Black elementary school principal in our school district. She worked her way up to Director of Teaching and Learning, making her the sole Black face in the district office, and as a result, I became the token Black girl. Solid grades, prom court, track records, college scholarships, I did it all. But it didn’t stop two of my white male classmates from threatening to hang me from a tree. It didn’t stop my brother’s classmate from telling him to go back to his slave master. It didn’t stop my sister from being pulled over on her bike. And it definitely didn’t stop any of the daily microaggressions that made those macroaggressions possible.

The dangers of existing as a Black or Brown face drowning in a sea of white is a trope the founders of classic horror could never capture. As Cherish Farrah and my lived experiences demonstrate over and over again, Blackness surrounded by whiteness sometimes evokes the kind of terror that renders you rageful and confused—in my case—or plotting and vengeful, in Farrah and Cherish’s case. All of it is justified. Using the horror genre to examine the everyday cruelty that Black people experience at the hands of white supremacy is perhaps the metaphor we need, and I’ll gladly consume it for as long as I can.