Katya Apekina, author of critically acclaimed The Deeper the Water the Uglier the Fish, opens her newest novel, Mother Doll, with a nesting set of characters linked by familial ties and the weight of generational inheritance. Zhenia, a medical translator in Los Angeles, finds herself pregnant. Meanwhile, her beloved grandmother is dying. And, her deceased great-grandmother Irina, formerly a Russian revolutionary, approaches a psychic medium named Paul, begging him to connect her with Zhenia so that she can tell a story that has, for many years, remained a secret, obfuscated by time, geography, and trauma.

In purgatory, where Irina exists as her teenaged self, school uniform and all, a group of people coalesce in voice and in pain. When Paul first hears them, they announce: “We are all dead and none of us have been able to move on. We talk at once. We are aggrieved.” These early declarations reveal the heart of Mother Doll. Apekina, through the two intersecting narratives of Zhenia and Irina, a deep understanding of the Russian Revolution, and a clear-eyed portrayal of how complicated and necessarily fierce relationships can be between mothers and their daughters, asks, in her novel: Is it possible to move through or past trauma by speaking it aloud? If someone bears witness to the parts of ourselves we have tried to separate because of shame, fear, or the unspeakability of an experience, does it make it more bearable to live with or through? How are the excruciating, unspeakable parts of our lives passed down from one generation to another, both through biology and/or through the stories we tell about ourselves and our lives?

I spoke with Katya Apekina over Zoom about the power of female rage, how shame can keep us stuck, and the limitations of language, particularly when describing trauma.

Jacqueline Alnes: What drew you to write about the Russian Revolution, and what did you take from writing with such depth and care about the time period?

Katya Apekina: I’m from Russia and it was this event that ended up impacting my family. No one in my family was directly involved in the Revolution, but they were politically active and it felt like this very complicated thing. On one hand, the fall of the monarchy seemed inevitable, and what happened after was very bad too, with Lenin and then Stalin. My family left in the ’80s, and this was before people were really allowed to leave, and really suffered under the totalitarian regime. Most families did.

I started researching the book around 2016. I didn’t really start writing it until the pandemic and I was thinking about revolution a lot because of what was happening in the U.S. I also was thinking about this desire that I was feeling, and one that my character Irina as a teenager was feeling, of wanting to burn everything down without a clear idea of a next step after that. I don’t think that’s true for all revolutionaries but she was a teenager when she got involved. What motivated her was not a clear political ideology, necessarily, but a feeling of anger, female rage, being on the outside of society, feeling less-than all the time, and wanting to burn it down. And isn’t that relatable?

JA: Part of the book seemed to me to be about agency and guilt and grief, and the way that violence can warp who we are or who we want to be. I was thinking about how young Irina is in some of the scenes. There’s so much about her life at the time that feels schoolgirl-ish. On one hand she seems so young, and on the other hand she has these things where she is starting to witness people in love or wonder what life will look like after this. While writing Irina’s role in the revolution, what did you think about girlhood and identity and the way those things were shaped by these events?

KA: She was sort of guided in terms of her thinking by a very charismatic teacher. For the teacher, a lot of what she was teaching was very theoretical, but Irina was very literal. She wanted action. I can imagine how exciting it would be to be Irina in that situation and feel like you have agency and feel like the things you are doing set off a chain reaction in an enormous historical movement and event. It is very powerful and very exciting but I don’t think she fully understood what it would lead. I don’t think she understood what that kind of violence fully means or what being exposed to war and deprivation and a society that doesn’t function, even if it was functioning badly before. Her girlhood ends.

The way the story is set up, the Irina we are hearing from is just one aspect of a woman who has lived a long life. If you were to talk to other aspects of that woman, she would have very different things to say. Her teenage self ceased to exist once she escaped from the Soviet Union. The person she becomes is very different than her teenage self. We are only hearing from one part of her. I was playing with this idea of parts, a common idea in therapy where you’re made up of many different parts, but the idea that we are a unified self is an illusion. There are often parts of us in conflict with each other. Maybe some people feel more whole than others, but when people go through the kind of intense trauma that she does, that part is separated out. There was blood on her hands, and she was feeling the larger energy of the revolution that was moving inside of her. She became a vessel for something bigger than herself.

JA: Even though she does have parts of herself that are separate, this book made me think about how those parts of us are never really separate; they haunt us and they haunt our offspring. It’s this weird tension between having this part of you who can speak from this place while knowing they can never truly go away even if you are not them anymore.

KA: Right. The pattern is when you reject that part of yourself and shame it, it stays around more. It digs in. It gets louder.

JA: This novel made me think so much about what kinds of traumas are unspeakable and how, even when people do try to put difficult histories into words, parts might be lost in the articulation, in the translation between languages and time, and even in the listening. I took away from the novel that there is power in story, but also an impossibility in conveying a story in all of its wholeness. Did you feel like that while writing?

KA: One thing that I often think about in my writing and in life, too, is not quite the inability for two people to communicate, but the gap that is never quite filled. You’re projecting so many assumptions onto another person, whether you’ve known them a long time or not. You think you and another person have a shared understanding and then it turns out they have an entirely different understanding. Language is so limited in what it can convey.

Books function in a similar way, in the sense that they’re giving you stuff but you project into them your own stuff. The reason you’re affected by books is because you’re bringing so much of yourself and your past into a story that reflects that back to you. It’s almost like windows, right as the sun is starting to set, where you can sort of see into them but you’re also seeing your reflection. There is a desire people have to connect, but at the same time their inability to see past themselves.

JA: Do you think knowing anyone else is ever truly a possibility?

When I had a daughter, I became aware of myself in a chain of women, a part of a series of people, a piece rather than an individual.

KA: I don’t know. It’s funny because having a child, you might think, oh, that’s a person you can know fully because you’ve been there since the beginning. But for me, even when my daughter was a baby, I felt like I didn’t know her fully. She is such a separate person from me. I think I was picturing it would feel like an extension of yourself to have a child, but it never felt that way at all. She has always felt like her own person. This idea of fully knowing and fully possessing are linked for me, and I feel like you can’t fully know or fully possess anybody.

JA: Trauma also impacts that. Thinking about the normal, hard parts of being a human in combination with these familial secrets or obfuscation of pasts due to trauma, how does that play into silence and how much we can know about another person or even about ourselves?

KA: There’s a trauma on a large scale of living in the Soviet Union, which was its own sort of trauma for a lot of people. There’s the trauma of the revolution, the trauma of the great grandmother abandoning her child, which is Zhenia’s grandmother, and that abandonment creating this inability for her grandmother to be a present or “good” mother to Zhenia’s mother, which she then tried to make up for by being a very good grandmother to Zhenia, and having this very different relationship with Zhenia than her mom. You really see how there’s the initial trauma and there’s the ripples from it and the effects of it.

I was talking to a friend, Ruth Madievsky, who wrote All-Night Pharmacy, and her character had not been an immigrant but had been carrying all of her family’s trauma without even understanding what it was. It’s an emotional weight. Zhenia feels it too. Her own life is perfectly fine and yet she’s feeling the weight of all this stuff that has happened to them. Why is she feeling so disconnected from her life when she’s not the one who lived through all these things?

This idea of inherited trauma is really interesting because sometimes grandchildren carry it and they don’t even understand the origin points for the fears they have; they see the effects but not the source, because the source happened before they were even alive. Often it was something that wasn’t talked about, either, so everything is in the negative space of this event and you weren’t even there for the event.

JA: Paul is an interesting character in that he tries to channel Irina’s narrative. The way he reacts to her story made me think about how we are changed by the telling of stories and also when we listen to stories. There are beautiful things that happen, like Paul understanding Russian. But he also turns to alcohol to cope. His body suffers as a result of being a conduit for this story. When we say these stories out loud and when we try to hold them, they impact us in ways that are important but also in ways that are harmful.

The reason you’re affected by books is because you’re bringing so much of yourself and your past into a story that reflects that back to you.

KA: Bearing witness is heavy. It takes a physical toll. This was something that was inspired by me spending a lot of time with my grandfather when he was dying. I was recording his memoirs for him. That feeling of an onslaught of someone pouring their story into you, and feeling like a receptacle for that story, was physically and emotionally taxing. I feel like there was some study where people who bear witness get worn out. Boundaries between people are kind of porous, and that’s what happens with Paul. The boundary between him and Irina becomes too porous, so he takes on parts of her. He can speak Russian and experience so close to himself what she experienced, and that definitely takes a toll. I feel like listening to people for extended periods of time, and interviewing people about things that aren’t necessarily heavy is tiring.

JA: It seems like listening is a form of care, but maybe it’s even more than that.

KA: It’s a form of witnessing. With Zhenia, it’s not her choice. She’s not consenting to some of it. It requires a giving something of yourself to give your full attention to another person and to empathize.

JA: Even while she might not want to listen, she can’t look away. It’s like a compulsion.

KA: She’s also curious. She wants to know, she wants to understand. She feels an obligation to her grandmother to understand. She also resents having to receive this story. It’s a big ask. There’s a point where she’s pregnant, very pregnant, and she’s just full. She’s carrying enough.

JA: So many of the prominent characters in this novel are women and mothers. They seem to carry so much: family secrets, children, their own ailing mothers, and the list goes on. What about motherhood or womanhood intrigues you?

What motivated her was a feeling of anger, being on the outside of society, feeling less-than all the time, and wanting to burn it down.

KA: After becoming a mother, I became more interested in the lives of mothers and a lot less interested in the lives of men. I feel like growing up, I was oriented toward pleasing men in some way, being chosen by them or something like that. I feel like part of the growing up process for me has been not being super interested in that any more.

JA: When I read about Zhenia being pregnant, I imagined this passing down of an inheritance, both physically and also emotionally, of this is who you are. The women in this book are caregivers, and they seem so aware of the harshness of the world or of the things they are supposed to be worried about and those things come out in parenting.

KA: When I was pregnant and when I had a daughter, I feel like I became really aware of myself in a chain of women. In a way, that was almost a zoom-out type of feeling because I was thinking so much about my own mother and my grandmother and I felt like I was a part of a series of people, like as a piece rather than as an individual.

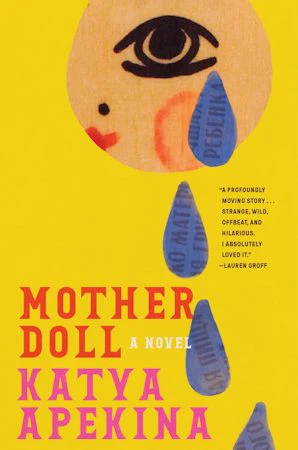

JA: Even thinking about the title, Mother Doll, prompts me into thinking about these dolls that nest within one another and belong together but they are also separate entities.

KA: When my grandmother was pregnant with my mother, my mother had in her already all of her eggs, one of which would become me. Literally a nesting doll. It feels like what was happening to my grandmother during her pregnancy would genetically impact who I would become as a person.

In the Soviet Union, it was common for people to have children really young and for the children to be raised by the grandparents; that was almost the default. I don’t think there was birth control that was very accessible, so it was common for children to be close with their grandparents. The parents were very young and starting their lives, basically, and so I think that bond between grandparent and grandchild is also cultural.

JA: For the people who make up the chorus of the afterlife in your novel, it seems like there are types of pain that will never leave you, that will stay with you into the beyond. I wondered, in thinking about inherited trauma and a desire for release, did you see ways where engaging in practices like storytelling or listening or diving deep into a history became a form of release?

KA: The ending of my book is about the transubstantiation of trauma into something else. The book is saying that if you deal with the stuff, you can then build a life that’s not encumbered by or defined by those things.

Read the original article here