Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

A few weeks ago, I had my author photo taken, completing a very peculiar and much-dreaded rite of passage toward achieving “literary legitimacy.” Barring the occasional sunglassed selfie, I have never loved the idea of a close-up photo, though this experience was particularly discomfiting. I was alone, unable to hide behind the buffer or camouflage of a group. With my made-up face and professional outfit, I also felt like an imposter, having spent the last few months costumed in pajamas and athleisure, discarding my mascara, eyeliner, and lipstick as if they were anachronisms of a foreign and antiquated past. Scanning my reflection like I would a piece of avant-garde art, I spotted flickers of the familiar amid a sea of uncomfortable inscrutability. I hoped that I looked sufficiently presentable —or at least sufficiently myself—to be “captured” by the lens.

The pressure, after all, was on. To a writer, an author photo is almost like a diploma. It stays with you for life (or at least until it is replaced or superseded by another one). And while it may not necessarily hurt you if it is “bad,” it will most certainly help you if it is “good.” “An enticing author photograph can really help your book,” advise Arielle Eckstut and David Henry Sterry in The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published. “This doesn’t mean you have to look like a model; it just means you have to look your best.”

While it may not necessarily hurt you if your author photo is ‘bad,’ it will most certainly help you if it is ‘good.’

It is tempting and perhaps even warranted for me to lament the significance awarded to the author photo as an unfair, misleading, and superficial distraction from literary purity. But I know such complaints will fall on unsympathetic ears. This is the age of Instagram, a world where the “beauty” of the artist is not a peripheral detail, but a commodity to be optimized, showcased, and marketed just as much—if not more than—the art itself.

Yet as I sat in my apartment experimenting with different poses, trying to emulate the blithe approachability of Ann Patchett or the sagacious wisdom of Jhumpa Lahiri, I couldn’t help but wonder: Who the hell came up with this idea? And why do they hate me?

The answer to my first question, I have since learned, is someone who lived a long, long time ago. In Uomini Illustri: The Revival of the Author Portrait in Renaissance Florence, Joyce Kubiski tells us that the author portrait has been an eminent and well-accepted motif since the first century B.C., with antecedents extending back into the Hellenistic era. Positioned at the beginning of a papyrus scroll, these ancient portraits displayed idealized versions of famous writers, who were featured as either the didactic “standing literatus” or the erudite “seated thinker.” Together with complementary statues, busts, relief carvings, mosaics, vases, and frescoes, these portraits served to commemorate the authors’ role in “the development and transmission of ideas” while bestowing godlike immortality to their work.

I couldn’t help but wonder: Who the hell came up with this idea? And why do they hate me?

As early Christians sought a conveyable medium for evangelization, the codex, or bound book, gradually replaced the scroll as literature’s dominant format. Kubiski tells us that the codex’s large expanse helped to make author portraits more accurate and longer lasting, allowing for a thicker and more durable application of paint that would have otherwise cracked with the endless rolling and unrolling of a scroll. During the Middle Ages, such portraits were reserved almost exclusively for the four Gospel writers and the early Church Fathers, though illustrators still stuck to the Greco-Roman paradigms of the “standing literatus” or “seated thinker.” In keeping with classical tradition, these Christian illustrators tended to depict highly idealized figures who minimally resembled the original authors themselves, their identification resting solely on an accompanying inscription or the inclusion of certain iconographic features such as dress or hair style.

During the Renaissance, renewed interest in the classics gave illustrators the license to commemorate the authors of antiquity alongside Christian patriarchs. Though physiognomically fuzzy, these “restored” portraits of classical writers were painstakingly accurate in terms of costume and setting, reflecting a concerted effort among artists to recreate aspects of the ancient world. Constituting the “frontispiece” of the codex, these portraits were often featured with illustrations of Renaissance-era patrons who had commissioned translations or reissues of classical texts. Subscribing to the Aristotelian notion that portraiture was a luxury reserved for the gifted or elite, these patrons sought to be immortalized alongside the ancients, their portraits helping to crystallize and canonize their identities as “Uomini Illustri” or “Famous Men.”

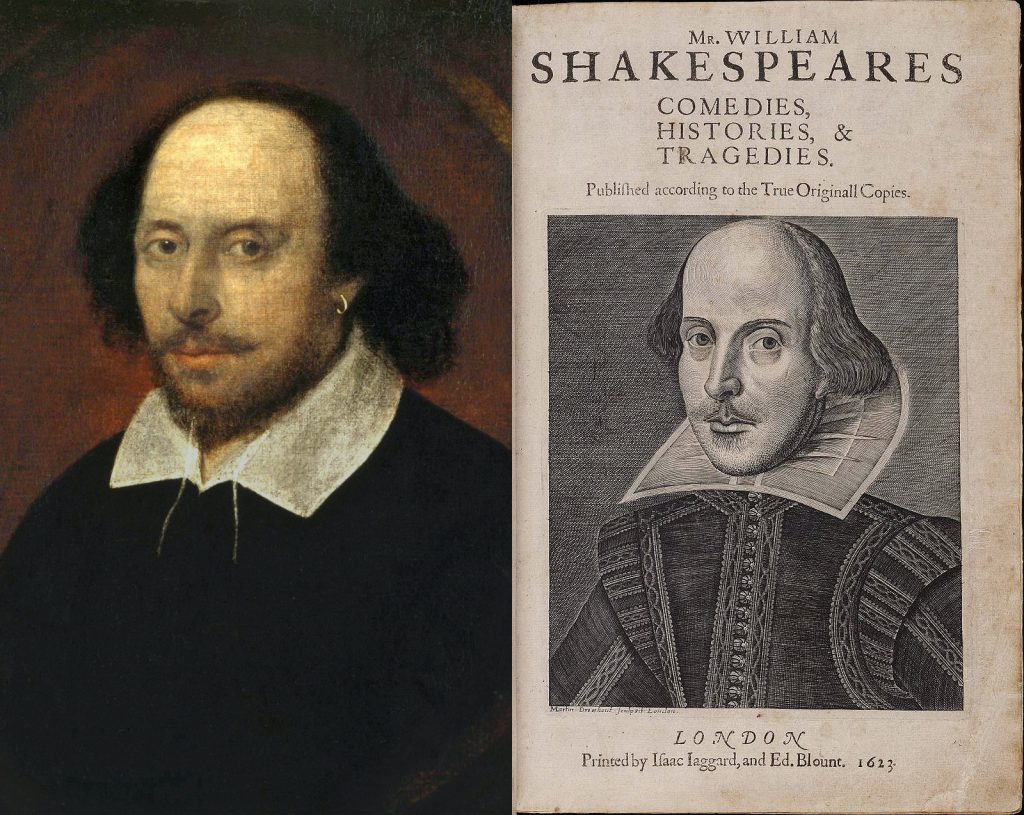

For most of the 15th and 16th centuries, portraiture remained an upper-class privilege, even for the most talented and influential of writers. In Searching for Shakespeare, former curator at London’s National Portrait Gallery Taryna Cooper writes that while the identity of the sitter in the so-called “Chandos portrait” remains inconclusive, its date of production (1600–1610) comports with the timeline of Shakespeare’s own material and social advancement. “It seems likely,” Cooper writes, “that Shakespeare chose to be portrayed after 1598, after he had purchased the lease on his house in Stratford-upon-Avon and had been successfully granted a family coat of arms.”

Yet even if Shakespeare had followed social protocol in waiting for his alleged portrait, there is evidence that he rebelled in other ways. Cooper suggests that, unlike most portraits of the era, the Chandos portrait makes no reference to the Bard’s social status or probity but rather underscores his individuality, featuring a playful bohemian with a knowing simper and a single gold earring. Interestingly, the follow-up to the Chandos portrait, a 1623 engraving by Martin Droeshout, also diverges from classical tradition. Appearing in the first printed edition of Shakespeare’s plays (aka the First Folio), the engraving is the only portrait that “provides us with a reasonable idea of Shakespeare’s appearance,” writes Cooper. Praised by Shakespeare’s contemporary Ben Johnson for its accuracy, it jettisons conventional iconography in favor of realistic depiction, putting the Bard’s characteristically arched brows, receding hairline, droopy eyes, and prominent nose on full and unapologetic display.

While it is impossible to know what Shakespeare thought of the Droeshout engraving (it was commissioned posthumously), we do know that not all 16th- and 17th-century writers were comfortable with such realism. In John Milton: A Biography, Neil Forsyth tells us that when Milton’s publisher asked for a portrait to accompany the soon-to-be-released Poems of John Milton (d. 1645), the 38-year-old poet suggested that the engraver, William Marshall, refer to a picture of him at age 21. What Marshall produced was an ironic and unforgiving compromise, with one half of Milton’s face appearing young and the other half saddled with a double chin and a contorted frown. When the publisher refused to withdraw the portrait, a vengeful Milton composed a coded retaliation to accompany the frontispiece: “You would say,” he wrote in Greek,

That this portrait was drawn by an ignorant hand, once you look at the living face; so friends since you do not see the likeness, laugh at the botched effort of this incompetent artist.

During the eighteenth century, writers began to exercise more control as portraits became more central to authorial promotion. Reflecting Romantic notions of self-expression and self-curation, books featuring an author portrait tended to be not only more expensive and more saleable, but also more personal, offering “a miniature surrogate of the book’s absent author.” Recognizing the power of the portrait while enjoying the still-maneuverable liberties of the brush and pencil, writers such as Alexander Pope, Benjamin Franklin, William Wordsworth, and Lord Byron took “great pains” to control and perfect their image as a performative reflection of their literary legacy, criticizing—or sometimes all-out rejecting—portraits which highlighted their physical imperfections, misrepresented their demeanors, or thematically deviated from their writing. Perhaps no one benefited from this artistic leverage more than the growing cadre of female authors, who, not unlike women today, were subject to harsh cosmetic criticism. Observers have long argued that Charlotte Brontë was both judicious and fortunate in her choice of artist George Richmond to paint her. In foregoing realism, Richmond chose to ignore Brontë’s characteristic pallor and fragility, instead depicting an ethereal woman with “eyes alight with the fire of genius,” wrote one turn-of-the-century critic.

The creative flexibility afforded by the painted portrait, of course, would not last forever. In the mid-19th century, photography became portraiture’s predominant medium, a change that writers of the late-Romantic and Naturalistic eras tended to embrace as an extension of artistic transparency. “They are honest,” wrote Walt Whitman of his preference for photographs over oils as he praised the way in which “the photograph lets nature have its way.” Whitman’s contemporary and friend Frederick Douglass was an even more passionate advocate of the photographed portrait. To Douglass, photography was not only an honest but also a singularly equalizing medium that liberated portraiture from the shackles of racist interpretation. “Negroes can never have impartial portraits at the hands of white artists,” he wrote, arguing that it was “impossible for white men to take likenesses of black men, without most grossly exaggerating their distinctive features.”

By the 20th century, photographic promotion had fortified the link between authorial photogenicity and authorial marketability.

Like many writers of his generation, Douglass made every effort to curate and publicize his photographed portraits, using them as promotional tools for his books, talks, and newspaper, The North Star. By the turn of the 20th century, this trend of photographic promotion had effectively fortified the link between authorial photogenicity and authorial marketability, all but cementing the (now very familiar) prototype of the picturesque “celebrity writer.” Throughout the early 1900s, photographed portraits of Mark Twain were repeatedly scattered across the pages of national magazines and newspapers as portraits of F. Scott Fitzgerald, the “hopelessly good looking,” clean-cut, preppy collegiate, served as a real-life advertisement of his novels, de-mythologizing the chimerical characters of Jay Gatsby, Amory Blaine, and Dick Diver. Though he was not as classically handsome, Ernest Hemingway’s looks too helped to bolster his consumer appeal, a fact that publishers knew and actively capitalized on. According to Leonard Leff, author of Hemingway and His Conspirators, Scribner’s 1929 serialization of A Farewell to Arms featured several photographs of Hemingway, signaling a “remarkable” departure from the magazine’s standard practice. Whether taken in Key West or Paris, the photos of Hemingway seemed to radiate “the silver-screen allure of Gary Cooper,” positioning Hemingway as both a famous writer and a consummate sex symbol.

Today, an alluring author photo has become less a “bonus feature,” as it was for Twain, Fitzgerald, and Hemingway, and more a golden ticket for literary success. “Interesting, beautiful or unusual photographs,” according to Eckstut and Sterry, “have a way of ending up in ‘pick of the week’ sections of newspapers, on the homepages of websites, or in the posts of bloggers.” Such “arresting visuals,” they tell the reader, can dramatically increase one’s chances of getting a feature or catching the eye of a publisher, publicist, or bookseller.

There is evidence to suggest that the stakes surrounding a good author photo are higher for women than they are for men, leading many “American lady authors of a certain age” to indulge in the airbrush—the modern-day equivalent of the oil-painted touch-up. Though many have fought against this pressure, regarding it as both a distraction from and an adulteration of the sacred “compact between reader and writer,” publishers remain stubbornly beholden to pretty pictures, even going as far as to “re-do” portraits of female authors from history. In 2007, the British publisher Wordsworth Editions commissioned a new portrait of Jane Austen to replace the 1810 original. “The poor old thing didn’t have anything going for her in the way of looks,” said Helen Trayler, Wordsworth’s managing director:

She’s the most inspiring, readable author, but to put her on the cover wouldn’t be very inspiring at all. It’s just a bit off-putting. I know you are not supposed to judge a book by its cover. Sadly people do. If you look more attractive, you just stand out more.

Responding to pressure to be a “‘highly promotable’ woman writer” (a pressure to which apparently not even Jane Austen is immune), many have boldly argued that books should be free of author photographs. Without such a distraction, writes Frances Wilson, a certain “dignity as well as democracy” could be restored to bookshelves, allowing “books [to] become words once again.”

To Wilson, I say sadly: “In Heaven, maybe.”

The author portrait has been here for a long time and—much to my chagrin—isn’t going away anytime soon.

While it is true that we live in a visually obsessed society, the origins of this society are both ancient and impenetrably solid. The author portrait has been here for a long time and—much to my chagrin—isn’t going away anytime soon.

But even in this age of aesthetically acquired likes and followers, there is still space for defiance and there is still space for truth. Of the hundreds of photos my wonderful and incredibly patient photographer supplied me, all are imperfect. In each and every one of them, I am able to identify a flaw, whether that be the line on my forehead, the creases around my eyes, the strands of grey in my hair, or the cellulite on my legs.

But in each, I am also able to identify something greater—a membership, a belonging, to the ancient and beautifully flawed family that is writing. My imperfections and insecurities are not what will disqualify me from joining this family. They are what will let me in.