Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

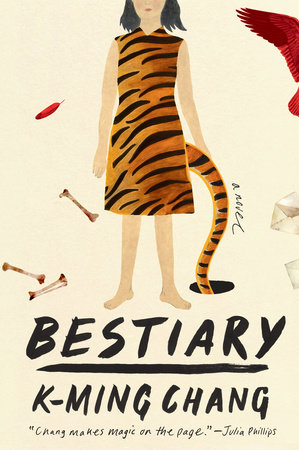

Before writing my debut novel Bestiary, I began a year-long process of translating letters written by my grandmother, many of which were addressed to people I didn’t know. While attempting these translations, I realized the impossibilities and possibilities of the task—the losses and gaps and misunderstandings that were embedded in my translations, as well as the moments of hybridity and discovery, where my own language layered over hers, hinging it open in strange ways and creating new meanings.

In Bestiary, the narrator also translates a series of letters from her grandmother that are spat out by sentient holes in her backyard, and these translations are a deeply embodied experience, a process of reliving and birthing. My novel is also about translation between generations, and how memories are mutated or transformed through the process of being inherited and re-embodied.

Throughout my writing process, I returned again and again to novels in translation from Chinese, both their translations and their original texts. I immersed myself in the process of translation as inevitable change and alchemy, and was especially drawn to novels in translation about queer life in Taiwan and China that explored the themes that compel me to write: exile, tenderness, violence, queerness as possibility and transformation.

Crystal Boys by Pai Hsien-Yung, translated by Howard Goldblatt

Published in 1983, Crystal Boys is often credited as the first gay novel written in Chinese. Whether or not this is true, it is a deeply formative novel in the Chinese-speaking world, and has taught me so much about subverting ideas of nation and citizenship. Set during the period of martial law in Taiwan, the book follows Ah-Qing, a young Taiwanese man who is brutally exiled from his father’s home after being caught having a romantic tryst with a fellow student. He flees to Taipei, where he discovers a community of gay men in New Park, creating a new home and sense of belonging among them. Crystal Boys is full of humor and love and desire and pain and myth—it’s not only about forging a new space of possibility, but about the limits of that process, too. It highlights the cyclical nature of generational violence and the enduring love between friends.

In the Face of Death We Are Equal by Mu Cao, translated by Scott E Myers

In the Face of Death We Are Equal draws upon the legacy of Crystal Boys. Many of the main characters share the same names as the boys from Pai Hsien-Yung’s novel, though the historical context is entirely different, and the language of this novel is compellingly strange, creating a surreal world that is more reflective of reality than more typical literary realism. Mu Cao’s innovative, non-linear novel follows Ah-Qing, a migrant worker from Henan Province who leaves his village in order to work in the city. Mu Cao centers the lives of gay, working-class Chinese migrant workers as they navigate a world of exploitation and precarity. This novel is observant and bizarre and humorous, completely unique in its narrative structure.

Notes of a Crocodile by Qiu Miaojin, translated by Bonnie Huie

Qiu Miaojin is an iconic Taiwanese lesbian writer, and her novel Notes of a Crocodile is a brutal and beautiful book. It’s the kind of book that feels like it’s swallowing you whole with its language and characters and self-destructive voice. The novel follows Lazi, a young Taiwanese lesbian who falls in and out of love with an older woman in the most all-consuming ways. Her friends similarly fall into intense, destructive relationships. Spliced into the book are allegorical vignettes about crocodile people who are exiled and othered in society. This classic novel draws from bildungsroman traditions, but it’s also formally innovative and regenerative, incorporating diary entries, scripts, vignettes, and obsessive monologues.

Beijing Comrades translated by Scott E Myers

Written anonymously and posted online, Beijing Comrades is an all-consuming novel that features one of the most frustrating narrators I’ve ever encountered. Set in late 1980s Beijing, the novel follows Handong, a seemingly cold-hearted businessman who picks up Lan Yu, a university student newly arrived to Beijing from Xinjiang. Lan Yu is vulnerable, naive, and sometimes elusive, while Handong can be incredibly cruel and obtuse. This is a novel about money and power that shrouds the possibility of romance, and though the ending feels unnecessarily tragic and sacrificial, it’s the kind of book that haunts you in your dreams after you read it in one sitting.

White Snake and Other Stories by Yan Geling

The title story of this collection of stories by Yan Geling features a lesbian retelling of the classic White Snake legend in Chinese folklore. Yan Geling’s writing is fluid, seamless, and beautifully understated in many moments, and the White Snake legend has always had subterranean queer undertones, which Yan Geling brings to the surface. The story switches between different narrative voices but is cohesive in its gorgeous, subtle use of language.

Angelwings: Contemporary Queer Fiction from Taiwan translated by Fran Martin

This anthology of queer fiction from contemporary Taiwan is an endless offering. The genre of tongzhi wenxue, or queer fiction, became especially prominent in Taiwanese literature during the 1990s. Featuring iconic women writers such as T’ien-Wen Chu and Qiu Miaojin, this anthology features a broad spectrum of styles and themes that incorporates mythology, religion, and daily life, and it’s worth reading for Qiu Miaojin’s story “Platonic Hair.”

Last Words from Montmartre by Qiu Miaojin

This innovative, visceral novel is written in letters and vignettes that can be read in any order. Qiu Miaojin’s work is brimming with emotional intensity, self-obsession, and desire. I often compare reading her work to being possessed—it feels like being haunted and absorbed. This novel—which feels also like an archive and artifact of a destructive relationship—is akin to being consumed by your own psyche and appetite. There is an immediacy and poetry to all of Qiu Miaojin’s writing, and this novel is unlike anything I’ve ever read.