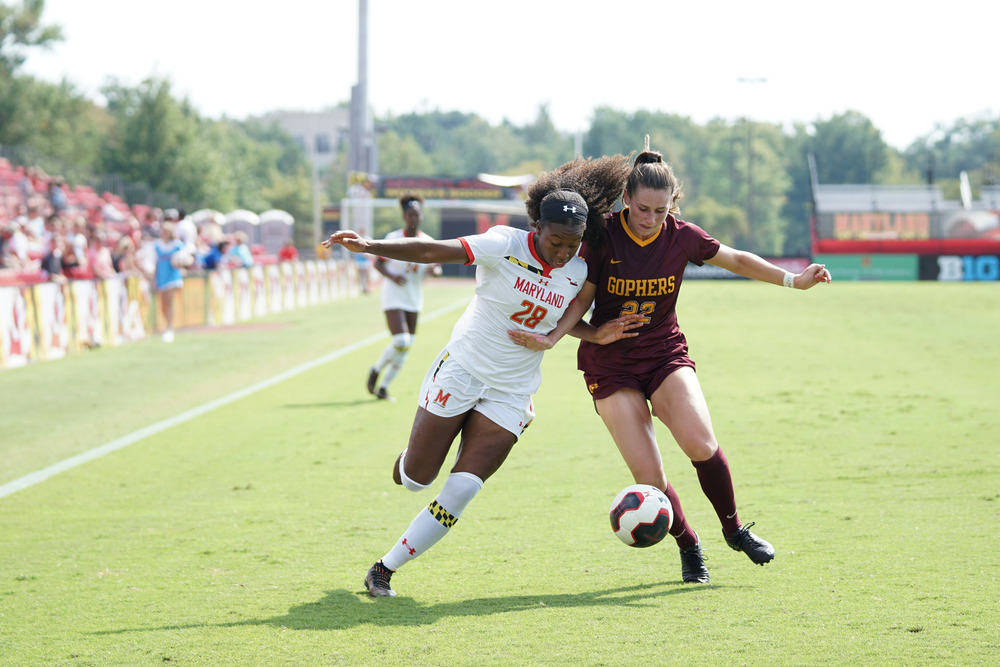

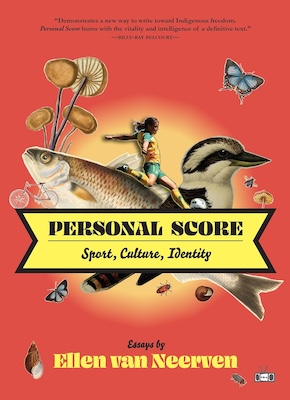

Football (or soccer) has always been a significant part of Ellen van Neerven’s life; they grew up playing the game, advanced to become an amateur player, and has always been what they call an “armchair enthusiast” of the sport. But EvN, the author of Personal Score: Sport, Culture, Identity, who presently lives in Brisbane, Australia, has not experienced only joy in their participation in sport. Instead, their love for the game was—and is—complicated.

As someone who identifies as queer, non-binary, and is of Mununjali Yugambeh and Dutch heritage, EvN, throughout their formative years, began to grapple with what it means to play within a system that is rampant with racism, homophobia, sexism, and so often reduces complicated facets of identity and being into binaries, like gender or the concept of winning vs. losing. In the “Pregame” to their book, EvN asks: “What does it mean to play sport on First Nations land?…Do we need to know the truth of land before we can play on it? Indeed, should we do anything on Country without knowing the truth?” These questions are as much a driving force for EvN in this collection as they are an invitation to the reader to consider intersections between sport, colonization, gender, race, environmental crises, and trans inclusion.

Stunningly kaleidoscopic in form, subject matter, and voice, the pieces in Personal Score range from deeply researched passages to lyric ruminations to sports writing to poems to narrative personal essays. In a book that is so much about how harmful binaries in sport, life, and thinking can be, the breadth of forms allows EvN to trace the way that historical violences, and present day refusals to acknowledge this violence, perpetuate deeply harmful systems that do not allow for full expressions of identity and humanity. I had the opportunity to speak with EvN via email about the power of language, the importance of eradicating harmful binaries, and what their relationship to sport has looked like at different points in their life.

Jacqueline Alnes: Football (soccer) becomes a way for you to examine the ills of colonization, LGBTIQSB+ inclusivity in sport, racial equity, the effects of climate change, and what it means to play sport on First Nations land. One of many beauties in the book was the way this signified to me how interconnected all of these issues are. Was all of this always in your mind as you stepped on a soccer pitch or did one thread lead to another and then to another?

Ellen van Neerven: Playing soccer (from a young age til recently) deeply informed the writing—I was determined to capture movement and connection on the page. I learnt a lot growing up participating in sport and traveling to play games. I became curious about what had happened and what was happening in the places I was on. I had the support of my family, Elders and broader communities when I was growing up. My learnings are on the pages and are by no means complete. The book contains many threads—all woven together.

JA: It’s clear that while sport has afforded you an opportunity, at times, to feel fully alive within and connected to your body, the gendered systems, microagressions, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia have also made the sport feel like a place where you and others don’t feel like they truly belong. In what ways has sport helped you better understand yourself, and in what ways, at least in the ways most teams and sport itself are usually structured, around binaries and with a goal of winning, has it taken you away from yourself?

Gendered systems, racial slurs, homophobia and transphobia deeply complicated my love for sport.

EvN: A recent thing I have learnt about myself is that I feel most me when playing sport. I feel affirmed in my queer trans Indigenous body running around a pitch and being involved in a game I love. However, competitive sporting environments were also places where I felt most policed, discomforted, and hurt. These are experiences I unpack in the book. Gendered systems, racial slurs, homophobia and transphobia deeply complicated my love for sport, and I know it had the same effect on many of my readers, who share their stories with me. Some queer and trans people, for example, are returning to sport at an older age, having been excluded or turned off sport when growing up. I was lucky to find supportive team environments when I was in my late twenties and found joy in sport beyond competition. On the sporting pitch I understood my capacity for compassion and loyalty towards others, I understood my limits of exertion and I learnt skills that extend off the pitch.

JA: When we see people who represent the communities we are a part of playing a sport, there seems to be potential for us to feel more connected to other people or even to become more hopeful about the future. I love the scenes where you talk about the way that watching particular players on television, like tennis star Ash Barty, brings you a specific kind of joy. What did it feel like to watch Barty play? And what do you think it is about sport that makes us feel this sense of connection and optimism while watching?

EvN: Our community got behind Ash Barty in a big way—we are so proud of her. It is an amazing feeling—watching an Indigenous athlete who grew up in a similar part of the world as you—go on to become the number 1 tennis player in the world. Of course this is not unpreceded, Evonne Goolagong Cawley was this for my mother’s generation, she is a Wiradjuri woman who was number one and won majors in the 1970s. I remember Mum suggesting I write about Evonne for a school assignment when I was about eight—instead of the four white Australian athletes that we had to choose from I did do this and it unlocked a curiosity in me to learn more. Forty years later, watching Ash’s journey on the world stage was hugely influential for me and the older generation and the younger generation. Ash is not only a beautiful player but has an incredible warm spirit that is infectious. From seeing the Aboriginal flag being flown in the crowd during her Wimbledon victory to Ash winning a home grand slam, this collective joy uplifted us during tough times where our communities were experiencing grief and injustice. So it was also healing. We were also in admiration in the way Ash chose to retire—at the age of twenty-five and at the top of the game. She exited the game on her own terms—not willing to sacrifice her happiness and the other things she wanted to achieve in her life.

JA: You write, “This is an ugly book that was born out of the ugly language I grew up hearing in this country.” There are so many moments in this book where language harms, whether it was insults you received at school, deeply problematic names of soccer pitches or towns, or racial epithets. But you also write that “language can always be taken back and used to our advantage.” I love how many different types of writing you include in this book, everything from narrative essays to lyric fragments of prose to poems. How did writing this book shape your relationship to language of both the harmful and healing variety?

EvN: Language holds so much power. It was painful but necessary to write about how language (namely English) has hurt me and others and freeing to write in ways that represent flow, fluidity—to use language (English and language of my mother’s people: Yugambeh) to hold and to be held.

JA: You write about how, “unlike whitefellas, First Nations people don’t necessarily subscribe to the binary of work and leisure” and instead consider sport to be a “part of life, part of work, part of education, and part of looking after Country.” The way colonizing Europeans historically only allowed men and the ruling class to participate in sport, and their emphasis on the importance of winning, have trickled down to the ways in which trans athletes are being harmed or pushed out of sport now. How, for you, do these harmful histories show up in sport in the present day?

I’d like the future of sport to be responsible to land, inclusive to all people and a space that can show leadership in restorative justice.

EvN: Yes, histories of exclusion and discrimination in sport still have impact today when we look at issues in sport like sexism, racism, queerphobia, transphobia, ablism and classism. Despite progress, there’s still generally a massive pay gap between athletes in male and female sport. Participants in sport often don’t feel like there’s avenues for transformative justice when racism is reported. LGBTIQA+ people often face barriers to participating and experience discrimination. Where a young person grows up might impact their access to sport.

JA: What was it like tracing the histories of Country and sport and colonization alongside your own personal history? What did you learn about sport, place, people, and yourself along the way?

EvN: I grew up about an hour’s drive from my traditional Country, where my grandparents were born, and my ancestors lived for thousands of years. Where I lived and still live is in a city on what has always been Yagera and Turrbal Country—neighbouring nation to my nation. Prior to colonisation, we developed strong reciprocal bonds nation to nation and travelled widely to practice ceremony and culture. As a sporty kid, the first occasions where I travelled were with my parents driving to games and tournaments. I was taught more information about the places where I was moving and travelling but I was also acutely aware of the disruptions, fractures and violence of colonisation that had impact on the places today. I learnt when something bad happens on Country and is not acknowledged, it translates into a bad feeling felt in the environment and this continues to ripple. When we can name what happened, when we can feel supported in place and in relationships, when we can speak out and have a voice—this can be a strong start in addressing the injustices of harm to people and environment.

JA: In regard to the environment, you write about invasion, land grabs, destruction, and the colonialist exploitation of the environment that has caused such irreparable damage. In the first few pages of the book, you ask both yourself and readers, “What does it mean to play sport on First Nations land?” As you collected the physical evidence of damage, language marking the deeply horrific histories that have happened in specific places, and thought about the way rising tides, fires, floods, pandemics, and more are wreaking havoc on communities and the natural world, what answers have you come to?

EvN: What does it mean to play sport on stolen land also is what does it mean to play sport in climate crisis. We are experiencing devastating climate events that are disproportionately affecting the world’s Indigenous people and most disadvantaged people. While researching the book, I came across information I hadn’t made the links to yet—like the link between injury and drought—from playing on hard ground.

JA: Throughout the book, you note how First Nations knowledge is so often undermined and disregarded, leading to climate crises, a reliance on harmful binaries that impact both individuals and communities, and many other ills. You write that “resilience” and “reconciliation” are thorny terms because of what they signify: “re-silence,” and “to repeat, continue…conciliation—to placate or pacify.” What might true healing look like, and is that even a possibility? What would that kind of reparation require?

EvN: First Nations knowledges are still being ignored, even in times of major crisis, and after major crisis. And when there is interest in traditional knowledge, it is often cherry-picking—say an interest in cultural burning after devastating fires but don’t see that cultural burning is but just one aspect of cultural land management. First Nations people always had an active role in sustaining the land and waterways. Governments need to put resources into cultural land management which includes practices such as cultural burning, and this needs to be in the hands of First Nations people. It is hard to heal from colonial injury when there is still so much disadvantage and injustice—for example high rates of incarceration, high chronic health risks and not being listened to by government on what the best ideas and solutions are for each community. Land back. Bring everyone home. Indigenous languages are also vital for the future. It would be transformative if every jahjam (child) had the chance to learn their language.

JA: Thinking about the future of sport, and of course the ways that sport is connected to and representative of so much else, what does an ideal future look like to you?

EvN: It is important for sport to be seen as so much more than singular—rather let us see sport in pluralities. There are many diverse ways of engaging with sport that go beyond mainstream nationalist narratives. Personal Score is about connecting to the land you’re on and play sport on. Ideally, I’d like the future of sport to be responsible to land, inclusive to all people and a space that can show leadership in restorative justice.

Read the original article here